Original to the Clarion-Ledger. By Jana Hoops.

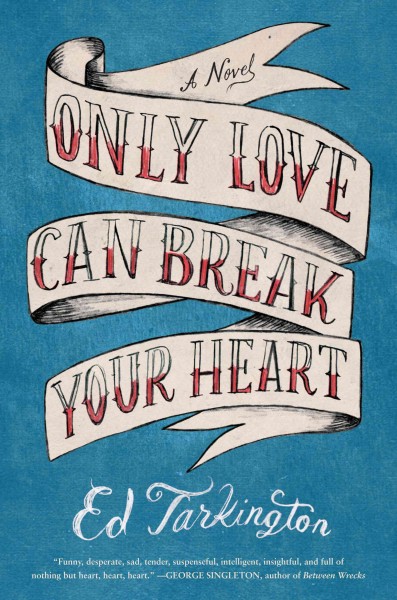

Nashville English teacher and wrestling coach Ed Tarkington releases his debut novel this month, “Only Love Can Break Your Heart,” after taking a circuitous route to add the title of “novelist” to his career accomplishments.

Nashville English teacher and wrestling coach Ed Tarkington releases his debut novel this month, “Only Love Can Break Your Heart,” after taking a circuitous route to add the title of “novelist” to his career accomplishments.

A distant cousin to Booth Tarkington, a best-selling literary novelist through the first half of the 20th century, the contemporary Tarkington says the memory of “Cousin Booth’s success left my father under the delusion that writing was a practical career choice. So I was never properly discouraged.”

Along the way, he earned a BA from Furman University, an MA from the University of Virginia and PhD from the Graduate Creative Writing Program at Florida State.

Tarkington’s formative years in Virginia shaped his early memories.

“I was born in Lynchburg, Virginia — not Lynchburg, Tennessee, the home of Jack Daniel’s whiskey, but, rather, of Jerry Falwell’s Old Time Gospel Hour. I grew up on the other side of town among the hypocrites and the sinners, also known as Presbyterians and Episcopalians.”

His career path to becoming a published author did not have a smooth start, he admits.

“Like a lot of young would-be writers, I floundered for a while,” he said. “I spent one year on a residential framing crew and the next teaching English at a small school in North Carolina, which I loved, but I wasn’t getting much writing done. I went to grad school at the University of Virginia to study literary theory, but scholarly life didn’t agree with me, so I ran off to Colorado to play at being Jack Kerouac. Eventually, I went back to school, enrolling in the Graduate Creative Writing program at Florida State.

“I fell in love, got married, started a family, and migrated to Nashville, where I now live, teaching and coaching, watching my little girls grow.”

A frequent contributor to Chapter16.org, Tarkington’s articles, essays and stories have appeared in Nashville Scene, Memphis Commercial Appeal, Post Road, the Pittsburgh Quarterly, the Southeast Review and elsewhere.

How did you become interested in language and writing?

I had many wonderful teachers growing up, but, eventually, in high school, I had two who really influenced me in a transformative way: a really ambitious and successful theater director named Jim Ackley, and Patty Worsham, my AP English teacher, who is still pretty much my hero. Patty taught me to love Shakespeare and Yeats. She also encouraged me to write and helped me discover contemporary writers like John Irving, who, being both a writer and a wrestler, really inspired me. Jim made us all feel like we were good enough to be professionals; our advanced acting class wrote a play our senior year, and that experience made me think, “man, you can do this.”

Please tell me about the kinds of works you’ve had published in other media.

When I was in graduate school, I spent a lot of time writing stories and sending them out to little journals, with little success. I took a brief stab at freelance magazine writing and flopped royally. So I decided to stick to teaching and novel writing and just hope for the best.

About a year after I moved to Nashville, Margaret Renkl, who is a really brilliant writer and editor here, had been hired by Humanities Tennessee to start up an online publication supporting Tennessee authors and book culture. Margaret was looking for contributors to the website, which they decided to call Chapter 16, because Tennessee was the 16th state to join the Union. Margaret asked me if I wanted to write essays and reviews for the website, and informed me that she would be paying for content. “Free book and a check?” I thought. “I’m in!”

I had no idea at the time that Chapter 16 would introduce me to this thriving literary community in Nashville revolving around Humanities Tennessee, the Southern Festival of Books, the Nashville Public Library and eventually, Parnassus Books. I got to connect with a lot of other writers and also get a byline in a number of different regional publications.

Is “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” your first novel? Tell me briefly about the story line.

“Only Love Can Break Your Heart” is my publishing debut, but not my first novel. I wrote another before, which was sort of a Cormac McCarthy, Robert Stone-type, a Southwestern noir. I worked on that book for seven years and had great hopes for it, but it didn’t sell.

By that time, I had been teaching high school and coaching for about four years. My life had gotten pretty tame; I had a hard time seeing my way back into the kind of world I’d spent the previous decade thinking and writing about. So I went back to my central Virginia childhood, drawing on memories and stories I’d collected over the years.

The narrator, Rocky, is a kid growing up in the small town South. He has an older half-brother, Paul, who is kind of the classic rebel-without-a-cause. Young Rocky idolizes Paul but doesn’t really grasp how troubled he is until Paul pulls a very cruel and vengeful stunt to lash out at their father and then disappears. Rocky’s childhood becomes defined by the absence of his beloved brother and by his involvement with Leigh Bowman, Paul’s ex-girlfriend, and with his new neighbors, who have an older daughter who sort of seduces young Rocky. Years after Paul’s disappearance, a grisly double-murder forces Rocky into a reckoning with the past and the present.

What inspired you to create this story? Is any of it influenced by any real-life occurrences in your life?

The primary relationship in the novel is between Rocky, the narrator, and his older half-brother, Paul. I don’t have a brother, but I do have a much older half-sister whose life has been utterly thwarted by mental illness. The pain and confusion I have always felt about what my half-sister’s illness did to her has haunted me for as long as I can remember. But I didn’t want to write a memoir or attempt in any way to “tell the truth;” I have neither the courage nor the authority to do so. So I turned my half-sister into a brother — Paul — and invented a narrator who is both at once the better and the worst parts of myself. I wanted to duplicate the feeling of growing up in the small-town South of the late ’70s and early ’80s, in a family that was both typical and strange, as most families tend to be below the surface.

The title of the book, according to the story, is a nod to Neil Young’s 1970 song of the same name. Was the story inspired in any way by the song, or was there any other connection?

When I first started imagining the characters and their personalities, I was listening to this music to help me find the mood and sensibility I was going for, and I just pictured Paul as a guy who idolized Neil Young. As I imagined him, Paul dealt with the pain of his dysfunctional childhood by identifying with Neil Young — or his idea, constructed from his music and his image, of what Neil Young was like.

As for the title — it just came sort of serendipitously. I was struggling to figure out what to call the book. Then one day I was driving to work listening to After the Gold Rush and “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” came on, and I just thought, “Eureka! That’s it.” I hope if Neil ever hears about this novelist stealing his song title, he will take it as the gesture of admiration it’s meant to be.

How would you describe your writing?

My favorite writers are the ones whose styles are very fluent and inviting. I work hard to make the language both pleasing and natural — lyrical, but also accessible.

As a high school English teacher, class sponsor, literary magazine sponsor and wresting coach — not to mention a husband and father — how do you have time to fit writing into your busy schedule?

Early to bed, early to rise. And I mean early.

What approach do you take in teaching your students to write? What do you encourage them to do or not do?

I try to train my students to write as if they’re writing for a general audience instead of for a teacher. I want them to think about what it takes to catch and hold someone’s interest in the Information Age, when there are so many forms of content competing for our attention.

Author Ed Tarkington (Photo: Glen Rose/Special to The Clarion-Ledger)

Do you have other works already planned — or that you hope to be planned — for future release? In what genre?

I am hard at work on another novel. I expect to have a draft finished by the end of the year. While it is very different from “Only Love Can Break Your Heart,” it’s written with the same kind of style and sensibility and will hopefully appeal to the same audience.

Ed Tarkington will sign copies of “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” at 5 p.m. Thursday at Lemuria Books in Jackson.

Read More

Karl Marlantes found a publisher in El Léon Literary Arts, a small press privately funded through donations. Led by author Thomas Farber, the operation is known to run on a $200 a year travel and entertainment budget and publishes literary works that might not seem commercially viable by mainstream publishers. By the time the 700-page Matterhorn was printed in softcover and review copies were sent out, a group of booksellers got the attention of El Léon by submitting Matterhorn to a first-novel contest. Soon Farber began getting calls from larger publishers. Eventually, a deal with the independent press Grove Atlantic was made and Matterhorn was released in hardback in 2010. Behind the scenes, Grove Atlantic’s Morgan Entrekin championed Matterhorn to booksellers across the country. The success of Matterhorn is due to the perseverance of its author, small presses, and the diligence of booksellers. It is a story of authenticity as opposed to overblown media hype.

Karl Marlantes found a publisher in El Léon Literary Arts, a small press privately funded through donations. Led by author Thomas Farber, the operation is known to run on a $200 a year travel and entertainment budget and publishes literary works that might not seem commercially viable by mainstream publishers. By the time the 700-page Matterhorn was printed in softcover and review copies were sent out, a group of booksellers got the attention of El Léon by submitting Matterhorn to a first-novel contest. Soon Farber began getting calls from larger publishers. Eventually, a deal with the independent press Grove Atlantic was made and Matterhorn was released in hardback in 2010. Behind the scenes, Grove Atlantic’s Morgan Entrekin championed Matterhorn to booksellers across the country. The success of Matterhorn is due to the perseverance of its author, small presses, and the diligence of booksellers. It is a story of authenticity as opposed to overblown media hype. This authenticity leads to a collectible book. The copies of Matterhorn printed in softcover at El Léon became advanced copies for Grove Atlantic’s hardcover edition. For collectors, that softcover is the true first edition. Matterhorn follows in the tradition of other great war novels like Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and James Jones’ The Thin Red Line.

This authenticity leads to a collectible book. The copies of Matterhorn printed in softcover at El Léon became advanced copies for Grove Atlantic’s hardcover edition. For collectors, that softcover is the true first edition. Matterhorn follows in the tradition of other great war novels like Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and James Jones’ The Thin Red Line.

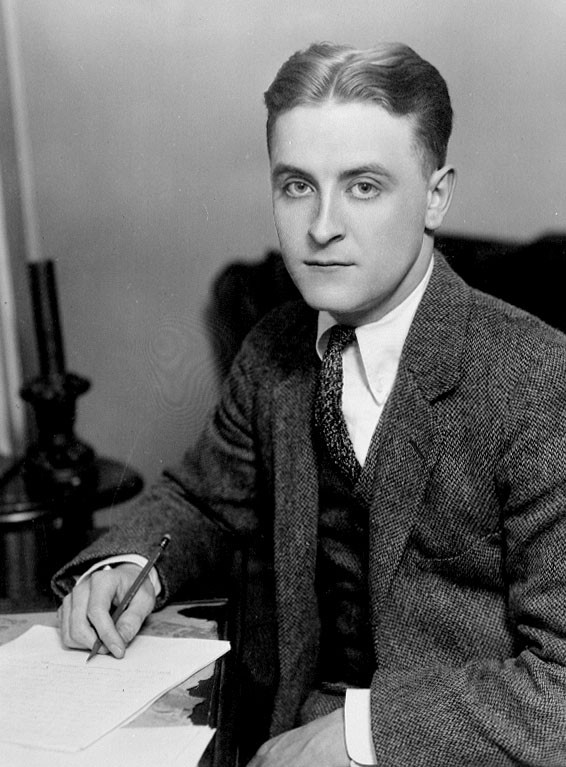

After his death in 1940, a longtime critic and friend Edmund Wilson secured permission from Fitzgerald’s family to publish “The Last Tycoon.” Wilson had never held back his negative criticism of the author’s work, even from Fitzgerald’s beginnings when Wilson published a satirical poem arguing that the young writer’s work was shallow and superficial. But Wilson was deeply affected by his death, expressing in a letter to Fitzgerald’s wife, Zelda: “I feel myself as though I had been suddenly robbed of some part of my own personality.”

After his death in 1940, a longtime critic and friend Edmund Wilson secured permission from Fitzgerald’s family to publish “The Last Tycoon.” Wilson had never held back his negative criticism of the author’s work, even from Fitzgerald’s beginnings when Wilson published a satirical poem arguing that the young writer’s work was shallow and superficial. But Wilson was deeply affected by his death, expressing in a letter to Fitzgerald’s wife, Zelda: “I feel myself as though I had been suddenly robbed of some part of my own personality.” Wilson, who must have felt some regret at being so critical of what he often called a “commercial” and “trashy” writer, decided to set the tone for Fitzgerald’s legacy by preparing his last manuscript and titling it “The Last Tycoon.” It would be published in book form accompanied strategically by “The Great Gatsby” and selected short stories. In the Foreword, Wilson announced “The Last Tycoon” to be “Fitzgerald’s most mature piece of work” and “the best novel we have had about Hollywood.” Other critics followed with similar praise. Novelist J. F. Powers asserted that “The Last Tycoon” contained more of his best writing than anything he had ever done and Fitzgerald’s best had always been the best there was.”

Wilson, who must have felt some regret at being so critical of what he often called a “commercial” and “trashy” writer, decided to set the tone for Fitzgerald’s legacy by preparing his last manuscript and titling it “The Last Tycoon.” It would be published in book form accompanied strategically by “The Great Gatsby” and selected short stories. In the Foreword, Wilson announced “The Last Tycoon” to be “Fitzgerald’s most mature piece of work” and “the best novel we have had about Hollywood.” Other critics followed with similar praise. Novelist J. F. Powers asserted that “The Last Tycoon” contained more of his best writing than anything he had ever done and Fitzgerald’s best had always been the best there was.” Fitzgerald’s influence, his attention to the illusive American dream, is seen in the work of Richard Yates, J. D. Salinger, Joseph Heller, and many contemporary writers. Mystery writer, Raymond Chandler, wrote that that “Fitzgerald is a subject no one has the right to mess up . . . He had one of the rarest qualities in all of literature . . . The word is charm—charm as Keats would have used it . . . It’s a kind of subdued magic, controlled and exquisite.” While Fitzgerald had sold less than 25,000 copies of “The Great Gatsby” at the time of his death, this book has now sold over 25 million copies worldwide.

Fitzgerald’s influence, his attention to the illusive American dream, is seen in the work of Richard Yates, J. D. Salinger, Joseph Heller, and many contemporary writers. Mystery writer, Raymond Chandler, wrote that that “Fitzgerald is a subject no one has the right to mess up . . . He had one of the rarest qualities in all of literature . . . The word is charm—charm as Keats would have used it . . . It’s a kind of subdued magic, controlled and exquisite.” While Fitzgerald had sold less than 25,000 copies of “The Great Gatsby” at the time of his death, this book has now sold over 25 million copies worldwide.

After the great success of his first novel,

After the great success of his first novel,  F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote his first novel,

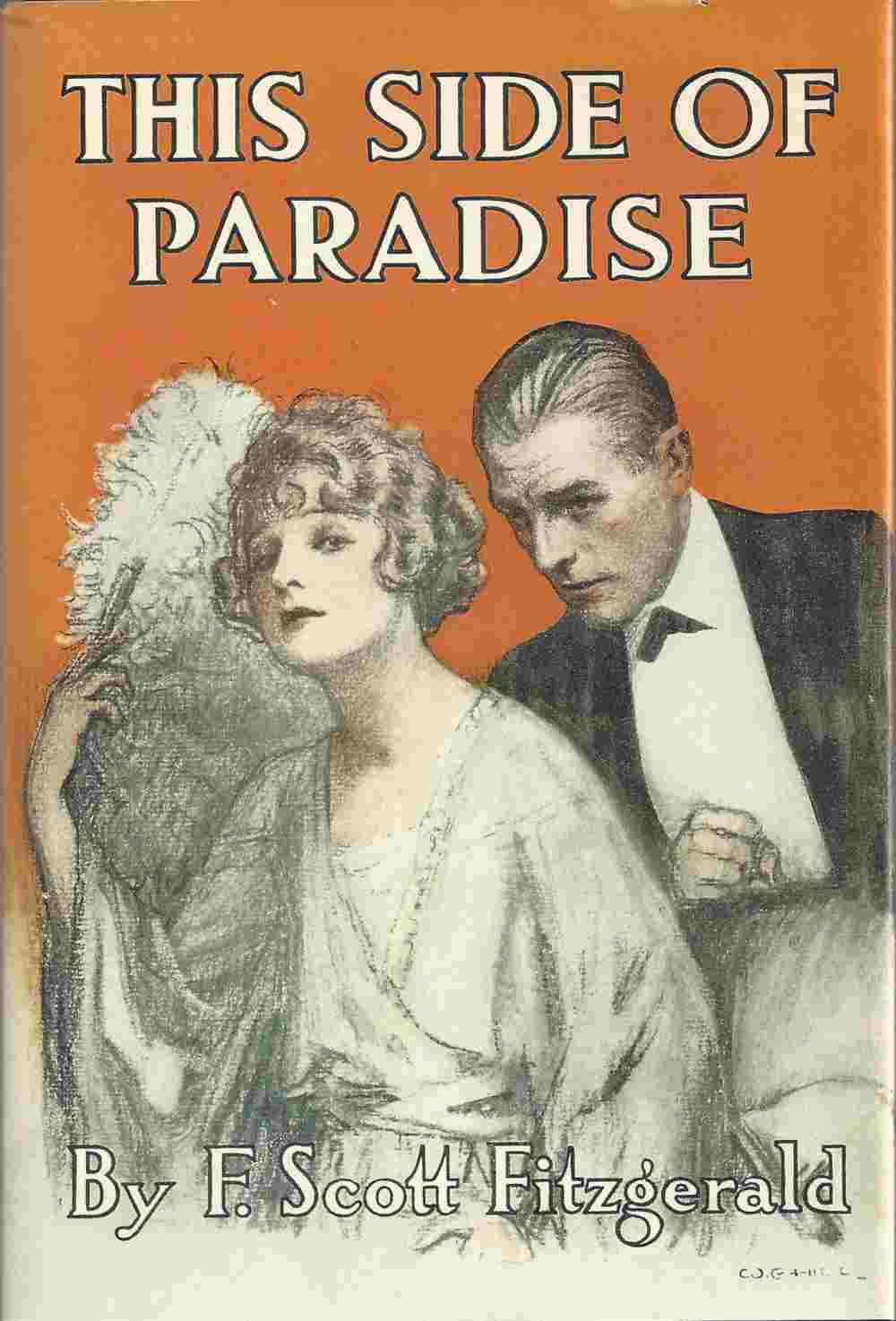

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote his first novel,  The dust jacket of any Fitzgerald first edition is key to its value. In the 1920s, publishers had only been making dust jackets for a short time. Readers often pulled them off and threw them away. Prior to the advent of the dust jacket, books were stamped with the title and author and often embellished with beautiful designs and gold stamped accents. The new dust jackets promoted the book, protected it, and advertised other books from the publisher. Because of this change in book design, it is very hard to find one of the 3,000 first printings of “This Side of Paradise”—a debut by a relatively unknown author—with the dust jacket present and in good condition. The era before climate control also did nothing to help preserve books.

The dust jacket of any Fitzgerald first edition is key to its value. In the 1920s, publishers had only been making dust jackets for a short time. Readers often pulled them off and threw them away. Prior to the advent of the dust jacket, books were stamped with the title and author and often embellished with beautiful designs and gold stamped accents. The new dust jackets promoted the book, protected it, and advertised other books from the publisher. Because of this change in book design, it is very hard to find one of the 3,000 first printings of “This Side of Paradise”—a debut by a relatively unknown author—with the dust jacket present and in good condition. The era before climate control also did nothing to help preserve books.

Coates’ list of sources are as equally intriguing as the entire book: Fulkerson’s “Early Days in Mississippi” (1885) is cited as an “excellent book of gossip”; “Ashe’s Travels in America” (1808) is noted as a “very interesting chronicle of an astonished Englishman, on a trip down to the Mississippi”; and Rothert’s “The Outlaws of Cave-in-Rock” (1924) is credited as a major source for the book.

Coates’ list of sources are as equally intriguing as the entire book: Fulkerson’s “Early Days in Mississippi” (1885) is cited as an “excellent book of gossip”; “Ashe’s Travels in America” (1808) is noted as a “very interesting chronicle of an astonished Englishman, on a trip down to the Mississippi”; and Rothert’s “The Outlaws of Cave-in-Rock” (1924) is credited as a major source for the book.

Nashville English teacher and wrestling coach Ed Tarkington releases his debut novel this month, “Only Love Can Break Your Heart,” after taking a circuitous route to add the title of “novelist” to his career accomplishments.

Nashville English teacher and wrestling coach Ed Tarkington releases his debut novel this month, “Only Love Can Break Your Heart,” after taking a circuitous route to add the title of “novelist” to his career accomplishments.

This year was a doozy. I consumed everything from nonfiction about

This year was a doozy. I consumed everything from nonfiction about