This review was originally posted on Tuesday, January 21, 2020. The introduction was added on Thursday, January 30.

Advance copies of American Dirt arrived at the store from Flatiron Books with a lot of fanfare, as do many books. I first heard about American Dirt from another reader at our store whose taste I tremendously respect, from whom I had first learned about Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi (another story about a culture very different from mine, and one of my favorite books of all time, albeit written by a writer with first hand cultural experience with parts of the story she was telling). I read American Dirt myself, and was genuinely moved by what I thought was a compelling human story written with what I still believe were good intentions. However, prominent members of the Latinx literary community have disagreed, arguing that celebrating such an inauthentic depiction of their culture would be a disservice to the real experiences of Mexicans and migrants (Rebuttal view points will be linked below the review). Reasonable people can debate what the exact guidelines should be for writing about other cultures, especially ones socially and economically marginalized by those in power, but one of the chief pleasures of reading fiction I have found is to expand experiences beyond what I can live myself. If we who are not Latinx wish to experience that culture, it feels appropriate to listen to Latinx voices, from authors to beta readers to critics, at whatever stage of the process we hear them.

American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins is, with all due respect to its competition, probably the best book of any kind that I’ve read in almost two years. It is a novel whose narrative and emotional power comes from being stretched taut between dual forces: senseless terror and redemptive generosity, life and death, dreams and nightmares, home and hope. I would recommend this book to anybody who reads for the same basic reason as I do: to have your soul made more expansive by the experience.

American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins is, with all due respect to its competition, probably the best book of any kind that I’ve read in almost two years. It is a novel whose narrative and emotional power comes from being stretched taut between dual forces: senseless terror and redemptive generosity, life and death, dreams and nightmares, home and hope. I would recommend this book to anybody who reads for the same basic reason as I do: to have your soul made more expansive by the experience.

Lydia Pérez is a normal woman with a middle-class life in Acapulco, Mexico, when that life is destroyed violently and instantly at her niece’s quinceañera as her entire family–except for her eight year-old son, Luca–is murdered because of her husband Sebastián’s reporting on the leader of a local cartel. If anything could even be added on to this horror, Lydia knows this cartel leader, known to her as Javier Crespo Fuentes, one of her most cherished, thoughtful customers at her bookstore.

Questions of complicity haunt Lydia in her spare moments. But she doesn’t have time for guilt; she doesn’t have time for grief. Her number one priority is to keep her son safe by leaving Acapulco, the state of Guerrero, and all of Mexico. Only in America, el norte, does Javier’s reach not extend. Both Lydia–and her gifted son, forced to act beyond his years–are plenty smart, but also not prepared, because who could bear to be prepared for this? Marked for death, with nobody in their family left to turn to, Lydia and Luca are forced to press every advantage, rely on their wits, and learn which strangers to trust, and, even more importantly, who not to.

Lydia and Luca form a family unit, of sorts, with fellow migrants Soledad and Rebeca, who are sisters from the mountains of Honduras escaping trauma and danger of their own. Lorenzo, a former sicaro from the very cartel Lydia and Luca are fleeing from, flits in and out of their journey, casting a shadow of doubt and fear on the hopes of escape.

Don Winslow, the author of cartel crime books like The Power of the Dog calls it “a Grapes of Wrath for our times,” and I think the Steinbeck comparison is apt. You could call American Dirt an issue book, in the way it humanizes the headlines, and shows who migrants are and what they face, but it definitely stands on its own two feet as a gripping story all on its own.

The balancing act of Cummins’ novel manages is to be tense and terrifying without seeming exploitative. The story shows the cruelty of a broken world without reveling in it. It shows not the machinations of power, from the perspective of the cartels or the politicians, but the consequences of it. It shows migrants as individual humans, each with different stories, even if there are all centered in tragedy. Each of those stories is worth telling, and each one, worth hearing.

Lemuria has chosen American Dirt as its January 2020 selection for its First Editions Club for Fiction.

Reading for further consideration:

- Dear Oprah Winfrey: 124 Writers Ask You to Reconsider ‘American Dirt’

- …You Ain’t Steinbeck: My Bronca with Fake…Social Justice Literature by Myriam Gurba (strong language advisory)

- Sandra Cisneros Calls Critics of Highly Controversial ‘American Dirt’ Novel “Exagerados”

- ‘American Dirt’ has us talking. That’s a good thing. by Reyna Grande (New York Times opinion)

- A Mother and Son, Fleeing for Their Lives Over Treacherous Terrain by Parul Sehgal (New York Times review)

When his grandmother, his beloved “G’ma,” shows up in an RV at the beginning of his spring break, to jailbreak him from being grounded, he jumps at the chance. He writes a note to his dad, and leaves his phone at home so he can’t be called. Just the wide open road, and the person he adores and trusts most in the world.

When his grandmother, his beloved “G’ma,” shows up in an RV at the beginning of his spring break, to jailbreak him from being grounded, he jumps at the chance. He writes a note to his dad, and leaves his phone at home so he can’t be called. Just the wide open road, and the person he adores and trusts most in the world. Since so much of John Hodgman’s new memoir,

Since so much of John Hodgman’s new memoir,  Mostly, I’m a football fan, with only a minor concern for keeping a toe in other waters of the sporting well, mostly for conversation purposes. And occasionally, the content would run a little too deep into the numbers and statistics for me to connect. But often, astonishingly so, it was a repository of top-flight long-form journalism, stories that connect you straight to the truths of the human heart (Faulkner’s “

Mostly, I’m a football fan, with only a minor concern for keeping a toe in other waters of the sporting well, mostly for conversation purposes. And occasionally, the content would run a little too deep into the numbers and statistics for me to connect. But often, astonishingly so, it was a repository of top-flight long-form journalism, stories that connect you straight to the truths of the human heart (Faulkner’s “

In the 1970s, rebellious Marilyn and straight-laced David fall in love by literally running into each other in a university hallway. Their life together unfolds into a strange domestic bliss when Marilyn becomes pregnant with their daughters in quick succession and decides not to finish undergrad. By 2016, when the book is set, their four daughters, Wendy, Violet, Liza, and Grace, are adults and living wildly different lives than their parents had envisioned.

In the 1970s, rebellious Marilyn and straight-laced David fall in love by literally running into each other in a university hallway. Their life together unfolds into a strange domestic bliss when Marilyn becomes pregnant with their daughters in quick succession and decides not to finish undergrad. By 2016, when the book is set, their four daughters, Wendy, Violet, Liza, and Grace, are adults and living wildly different lives than their parents had envisioned. Raphael Bob-Waksberg’s book,

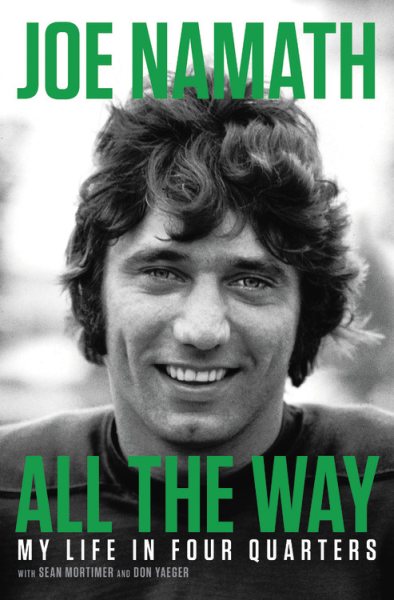

Raphael Bob-Waksberg’s book,  What was going to talk about here? Oh, yes. Joe Namath. Joe Willie. Broadway Joe. And, specifically, his new memoir,

What was going to talk about here? Oh, yes. Joe Namath. Joe Willie. Broadway Joe. And, specifically, his new memoir,

But if I told you Ocean Vuong’s novel debut

But if I told you Ocean Vuong’s novel debut  Knight’s new novel, set in 1994 at a boarding school in rural Virginia, is told from the perspective of Lenore Littlefield, a pregnant student of hidden talents and opaque motivations, and two lonely faculty members ostensibly charged with the education and guidance of Littlefield and her peers. The first person to whom Lenore reveals her predicament is her well-intentioned but somewhat indecisive history teacher, Lucas Bishop.

Knight’s new novel, set in 1994 at a boarding school in rural Virginia, is told from the perspective of Lenore Littlefield, a pregnant student of hidden talents and opaque motivations, and two lonely faculty members ostensibly charged with the education and guidance of Littlefield and her peers. The first person to whom Lenore reveals her predicament is her well-intentioned but somewhat indecisive history teacher, Lucas Bishop. Roommates in college, Helen and Charlie were opposite forces who became incredibly close. Helen was more scientific and analytical, a quiet woman who made herself known in the academic world, while Charlie was magnetic and outgoing. She was one of those people who everyone wanted to be around. After graduation, the women drifted apart. They both had children, Helen on her own and Charlie with a husband, and they made great strides in their professions. Helen became a theoretical physicist at MIT and published accessible books about physics, and Charlie became a screenwriter in Hollywood.

Roommates in college, Helen and Charlie were opposite forces who became incredibly close. Helen was more scientific and analytical, a quiet woman who made herself known in the academic world, while Charlie was magnetic and outgoing. She was one of those people who everyone wanted to be around. After graduation, the women drifted apart. They both had children, Helen on her own and Charlie with a husband, and they made great strides in their professions. Helen became a theoretical physicist at MIT and published accessible books about physics, and Charlie became a screenwriter in Hollywood.