By Jim Warren. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (March 8)

In The Last Taxi Driver, Lou Bishoff drives for Mississippi All Saints Taxis in Gentry, a university town in North Mississippi. His black 1995 Town Car has seen better days–the roof leaks, the brakes are gone, the shocks are shot, the horn doesn’t work, and the tires are bald. Lou’s future is uncertain. Uber is moving into Gentry. His relationship is over, assuming he can convince her to move out. An old nemesis is back in town after cutting off his ankle bracelet and hitchhiking from Kansas.

In The Last Taxi Driver, Lou Bishoff drives for Mississippi All Saints Taxis in Gentry, a university town in North Mississippi. His black 1995 Town Car has seen better days–the roof leaks, the brakes are gone, the shocks are shot, the horn doesn’t work, and the tires are bald. Lou’s future is uncertain. Uber is moving into Gentry. His relationship is over, assuming he can convince her to move out. An old nemesis is back in town after cutting off his ankle bracelet and hitchhiking from Kansas.

Albert Camus said, “The absurd is the essential concept and the first truth.” Maybe Al was a cabbie? Lou’s taxi has three air fresheners–Bigfoot, Shakespeare, and a flying saucer–besides working well as conversation starters, they help ward off smells so varied and offensive that he must keep Ozium and Febreze at the ready for backup. Lou’s a Buddhist, but a bad one, “the worst Buddhist in the world.” Nevertheless, he reads about Buddhism between fares in hopes that it might quell the urge to raise his middle finger in traffic. Then he gets another dispatch—All Saints dispatches come by text to thwart the competition’s radio spying—and he’s off on a run while his boss Stella watches through an onboard camera.

Lou works days; he’d rather avoid the drunk college students. He takes people to work, to shop, or to the doctor. He makes deliveries. If you got arrested last night and need a ride this morning from the jail to the vehicle impound lot, Lou’s your man. He’s also there if the hospital releases you to go home, but there’s no family to pick you up. He’ll be there when you get out of rehab, too, if it’s the good rehab, the one next to the VD clinic. He’ll drive you to Clarksdale, Memphis, or across town. Two bucks a mile outside city limits, though, and two dollars for any extra stops.

Gentry, of course, resembles Oxford. It’s no coincidence that Durkee drove an Oxford taxi for a couple of years. At one point, he was driving over 70 hours a week. Durkee includes a chapter filled with advice for Mississippi drivers right in the middle of the book, like an intermission. “Safe driving is all about the neck. Pride yourself in how much you employ your neck while changing lanes. Approach driving as a neck exercise.” Ditch the sunglasses (they create blind spots). Never blink your headlights at a UFO. And of course: “Your main job as a driver in Mississippi is to anticipate stupidity.” Indeed.

The Last Taxi Driver is a pleasure to read. We waited a long time for second novel from Durkee. It was worth the wait. Durkee’s language is unadorned and direct. It’s first person Lou, explaining the North Mississippi taxi business and narrating as we ride shotgun on a long, strange shift. The novel is dark, but quite funny. Lou has a knack for overthinking that turns even the normal stuff into a comedy routine. And Lou has stories to tell, stories about albino possums, UFOs, and adolescent trauma. As the day shift turns into a night run home from Memphis, with a yellow-eyed transplant surgery escapee on board and a gun under the seat, things get … well, they get darker.

Durkee was raised in Hattiesburg. He attended Pearl River Junior College, graduated from Arkansas, pursued a creative writing degree at Syracuse–he started the program with George Saunders, was taught by Tobias Wolff–and ultimately obtained his MFA back at Arkansas. He’s lived in Oxford for ten years. His first novel was Rides of the Midway, published twenty years ago. His memoir Stalking Shakespeare is scheduled for publication in 2021.

Jim Warren is a lawyer in Jackson. He collects books, enjoys music, and occasionally writes about both.

Signed first editions of The Last Taxi Driver can be found at Lemuria and at our online store.

Bass Reeves—a real, historical figure—was born a slave on an Arkansas plantation in the 1840s. In Sidney Thompson’s new novel,

Bass Reeves—a real, historical figure—was born a slave on an Arkansas plantation in the 1840s. In Sidney Thompson’s new novel,  Oxford’s Michael Farris Smith reinforces his rising prominence as “one of Southern fiction’s leading voices” with his newest Southern noir offering,

Oxford’s Michael Farris Smith reinforces his rising prominence as “one of Southern fiction’s leading voices” with his newest Southern noir offering,

In

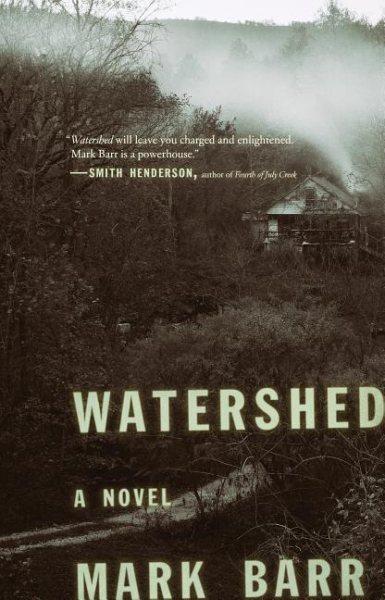

In  Mark Barr’s debut novel

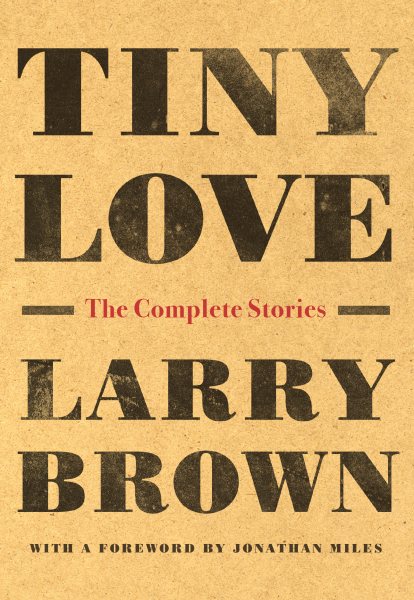

Mark Barr’s debut novel  Fans of the late Oxford author Larry Brown need wait no longer to own a collection of his career short works in one volume, with the release of Algonquin’s

Fans of the late Oxford author Larry Brown need wait no longer to own a collection of his career short works in one volume, with the release of Algonquin’s

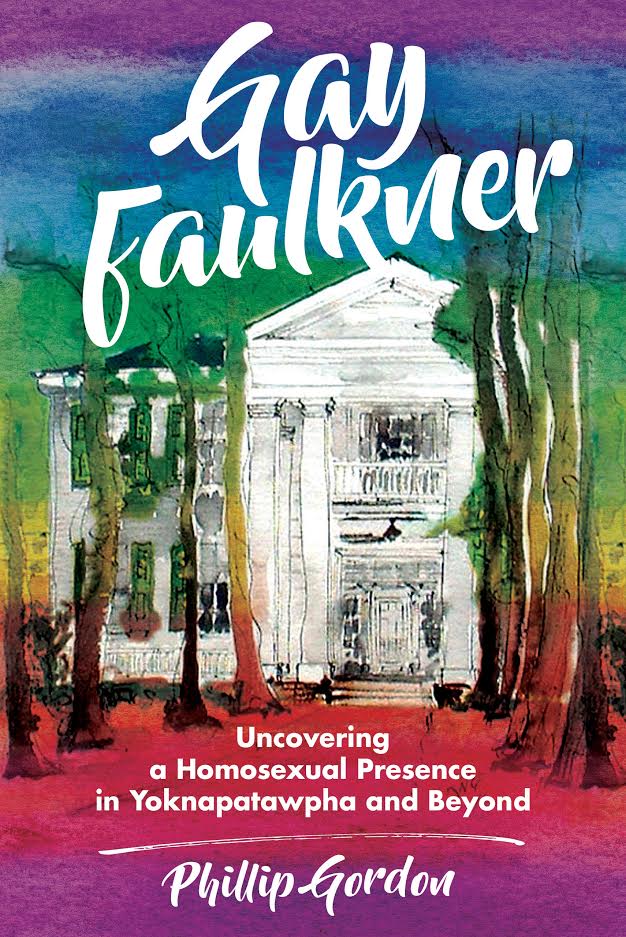

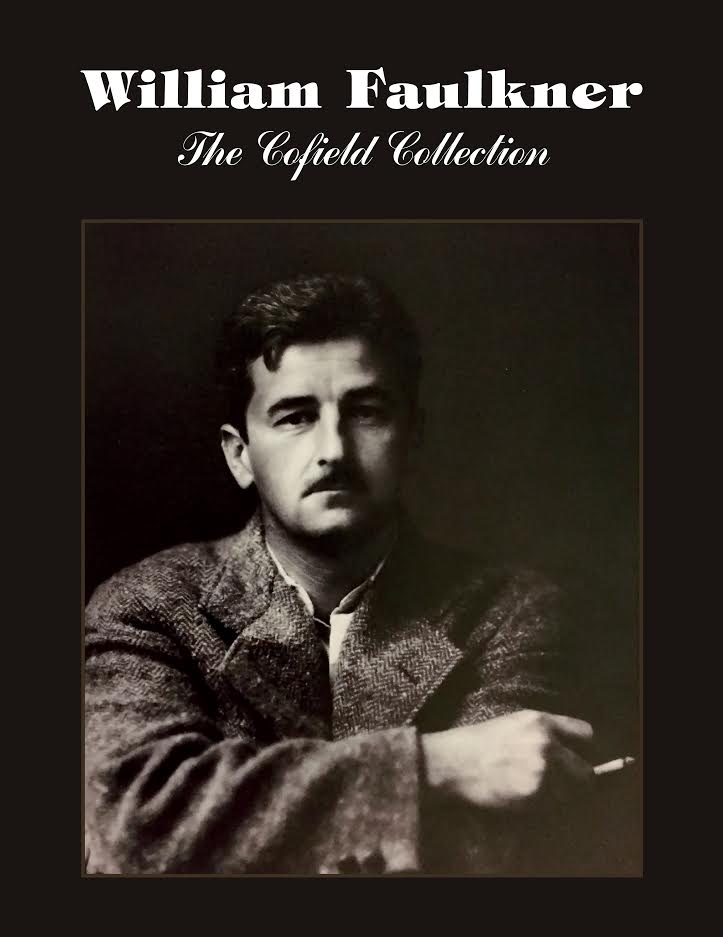

“It wasn’t easy to get a smiling photograph of William Faulkner!” That was the fond, exasperated comment of J.R. “Colonel” Cofield, the Oxford photographer in whose studio Faulkner sat for the portraits that graced the dust jackets of his novels.

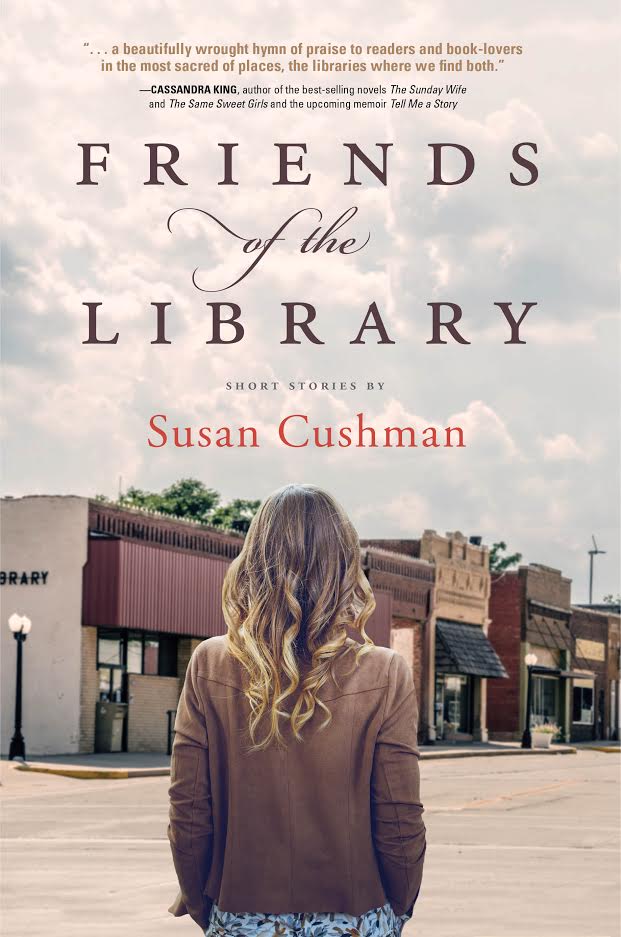

“It wasn’t easy to get a smiling photograph of William Faulkner!” That was the fond, exasperated comment of J.R. “Colonel” Cofield, the Oxford photographer in whose studio Faulkner sat for the portraits that graced the dust jackets of his novels. Hosted by each site’s Friends of the Library, a non-profit advocacy group aimed at supporting public libraries through fundraising and promotion, Adele adapts her program to the group and, depending on their interests, discusses either her novel, which deals with a sexually abused graffiti artist, or her memoir, which details her experiences with her mother’s struggle with Alzheimer’s.

Hosted by each site’s Friends of the Library, a non-profit advocacy group aimed at supporting public libraries through fundraising and promotion, Adele adapts her program to the group and, depending on their interests, discusses either her novel, which deals with a sexually abused graffiti artist, or her memoir, which details her experiences with her mother’s struggle with Alzheimer’s.