Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Thursday print edition (August 16)

Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Jack E. Davis, author of The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea, will be among the more than 160 official panelists who will appear at the Mississippi Book Festival Saturday, where he is scheduled for two thought-provoking events.

Davis will sign copies of The Gulf on the Mississippi Capitol lawn at 9:45 a.m., followed by an appearance in the American History panel at 10:45 a.m. in the C-SPAN Room (the Old Supreme Court room) in the Capitol building.

At 2:45 p.m. he will participate in an informal, in-depth discussion with Dr. Melissa Pringle, senior principal scientist and vice president of Allen Engineering and Science in Jackson. Afterward, he will host a Q & A session with Festival goers. The dialogue will be held in State Capitol Room 202, and those interested are asked to arrive 30 minutes early. Details are available at msbookfestival.com.

Davis said he wrote The Gulf because he was interested in restoring what he calls “an American sea,” to the conventional historical narrative of America.

Davis said he wrote The Gulf because he was interested in restoring what he calls “an American sea,” to the conventional historical narrative of America.

“Look at any general history of the U.S.,” he said, “and you are not likely to find the Gulf in the index, and, at the most, mentioned in passing in the text.”

He wants his readers to realize that the Gulf of Mexico is important to every American, not just “Gulfsiders.”

“All Americans . . . have a historical and ecological connection to the Gulf, and I sought to reclaim the Gulf’s true identity, which I believed had been lost to the BP oil spill and Hurricane Katrina,” he said. “I wanted people to know that the Gulf is more than an oil sump or hurricane alley – that it is an ecologically vibrant place with a rich, interesting, and informative history, meaning it speaks to who we are as a people.”

The author’s fascination with the Gulf began at age 10, when he spent much of his childhood along the Gulf Coast towns of Fort Walton Beach and the Tampa Bay area of Florida. After undergraduate school in Florida, he completed a doctoral program in history at Brandeis University, near Boston.

It was research opportunities for his dissertation at Brandeis that brought him to Jackson in the early ‘90s – a two-year stint that resulted in his first book, Race Against Time: Culture and Separation in Natchez Since 1930, which won the Charles S. Sydnor Prize from the Southern Historical Association for the best book in Southern history in 2001.

Davis said he came to realize “that I needed to write the dissertation in Mississippi to capture the sense of place that I wanted to convey,” adding that he “also met a lot of nice people in Jackson,” some of whom would become close friends.

He later pursued studies in environmental history, realizing it had become his “true passion.” Today he teaches classes in American environmental history at the University of Florida, including courses like The History of Water, The History of Sustainability, and History by Nature.

Among other books by Davis are An Everglades Providence: Marjory Stoneman Douglas and the American Environmental Century, (a biography of Douglas which won the gold medal in nonfiction from the Florida Book Awards); and Only in Mississippi: A Guide for the Adventurous Traveler, which he co-wrote with his friend Lorraine Redd.

In the process, Davis acknowledges, he learned things about the Magnolia State that have stayed with him.

“I’ve said more than once that Mississippians are the nicest people I’ve ever met,” Davis said. “One of things I love about Mississippians is that they are always looking for some type of connection to you. ‘Where are you from and who’s your people?’ they’d often ask, and, more often than not, (they would) find a connection.”

Below, he shares a bit of inside information about the writing of his Pulitzer Prize-winning eighth book.

The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea is an exhaustive history of the Gulf of Mexico and its enormous impact on the human species – throughout the United States and beyond. How did you develop your strong interest in this topic?

Jack E. Davis

Having grown up on the Gulf coast, spending a lot of time in and on it, I developed an intimate relationship with the Gulf. Whenever I was away from it, when I was in the Navy after high school, enrolled in graduate school, living in Birmingham, where I taught at UAB for six years, I missed it. I missed it not being a short drive from me, its smell, and its weather, not to mention its sunsets.

After finishing the Marjory Stoneman Douglas book, which is really a dual biography of a person and a place (the Everglades), I thought about writing another biography of a place. Given my background, the Gulf was a natural fit, and when I explored the topic I learned no one had written a comprehensive history of it. I spent five to six years researching and writing the book.

How has your Pulitzer win impacted your life?

It has taken over my life for now. I didn’t expect that. Didn’t know what to expect. Every day I’m fielding requests to speak or to write something. I have two dozen talks on my calendar for the fall, and 2019 is filling up. Receiving the prize is a great honor. I never in my wildest dreams thought the book could win – even after it received the Kirkus Prize in November and was chosen as a finalist for the National Books Critics Circle Award – or that I would ever be a Pulitzer Prize-winning author.

People ask what it feels like to win a Pulitzer, and I say it feels like someone else’s life. But as I see it, the recognition is not for the author but the work, as Faulkner once said. In this case, it is also recognition for the sea itself. It has been heartening to see positive attention for a change come to this wonderful body of water, attention turned toward the Gulf for something other than a horrific hurricane or oil spill.

Considering the depth of this book, what prompted you to take on such a substantial project?

My last book was 200 pages longer than this one, so writing this book felt something like downsizing. That said, I was initially daunted by how to organize and compose a book about a sea. I knew I wanted the natural environment, not human events, to guide the story, the biography, of the Gulf. I wanted to show nature as an agent in the course of human history, as it indeed is but as it is not regarded by most historians.

To bring nature to the forefront, I organized the chapters around natural characteristics of the Gulf – birds, fish, estuaries, beaches, barrier islands, weather, oil – and integrated nature writing with historical narrative, saving human stories to shape the narrative and illuminate the relationship between civilization and nature.

Your mention Mississippi often in The Gulf, describing many historical events (hurricanes, man-made interventions to its shoreline, seaside development, tourism, etc.), and devoting an entire chapter to the creative drive and devotion to nature that defined the life of artist Walter Anderson. As a Gulf state, how are we doing environmentally and in respect to conservation efforts? How do we compare to other Gulf states?

Mississippi is pretty representative of the other Gulf states. They’ve all engaged with the environment in both wise and unwise ways. All the states have squandered the biological wealth of the great estuarine environment that the Gulf is, mainly by destroying it needlessly, sometimes unwittingly but other times knowingly.

Places like Ocean Springs have been smart about controlling growth, and Jackson County has been thoughtful about protecting its coastal wetlands and the Pascagoula River.

We have to attribute these measures to a lot of people who understand the connection between a healthy natural environment and a healthy human population. They are the heroes in this book, thousands of volunteers and underpaid staff of nonprofit or government organizations, and they are in every Gulf state, and we who enjoy the Gulf and its waters and wildlife owe them much.

In the book, you say it’s common to cry “natural disaster” after weather events “carry away beaches” and destroy property, and you explain the role of “human behavior” in such occurrences. Can nature and local economies in Gulf cities work together successfully?

Absolutely. In the 1970s, most of the bays and bayous and sounds around the Gulf were edging toward ecological collapse from unrelenting pollution, mainly industrial and wastewater discharges, and careless engineering projects. But we’ve since cleaned up those bodies of water, brought them back to be thriving places again.

Tampa Bay was a mess when I was growing up. It is clean and full of life now, hosting bird species I never saw growing up, and the economy around the bay is as robust as ever. Two decades ago downtown Pensacola was a desolate place, but after the water utility removed its broken-down worthless wastewater treatment plant out of the area, downtown quickly came alive. It’s booming, a major draw for locals and tourists. I end the book telling the story of Cedar Key, Fla., and what the people there have done to coexist successfully, to its economic benefit, with the estuarine waters surrounding it.

Your skill as a writer is breathtaking, as you weave history and ecology with the wisdom and reflection of great writers and artists while examining the past and future of the Gulf, an inimitable force of nature. Explain how you’ve developed your unique and powerful style of writing.

I read good writing and pay attention to the composition of paragraphs and the construction of sentences and the selection of descriptive words, and how the author tells a compelling story. I study the writing as I read. In my own writing, I am as interested in getting the words right as I am in getting the history right. I’m a slow writer, a plodder, and I revise, revise, revise.

Writing the opening paragraphs of the book, the last words I wrote for the book, took a month of false starts and endless revisions. As important as anything, I have a writing partner, Cynthia Barnett, author of the superb book Rain: A Natural and Cultural History. She reads in draft everything I write, and I read everything she writes, and we trust and listen to each other.

As I tell my students, identifying your intended audience at the outset is essential, and once you do, imagine them beside you as you write, asking yourself constantly, “Will they understand what I am saying here, will I bore them with the way I am speaking to them, or will my writing keep them engaged?”

Please tell me about your next book you are working on now.

My next book is titled Bird of Paradox: How the Bald Eagle Saved the Soul of America. It is a cultural and natural history of the bald eagle, which lives exclusively in North America, that looks at the historical relationship between people and the bird, from pre-European native cultures to modern American society.

I am interested in how this bird came back from near population collapse in the lower 48 states in the 1960s and in how the American rendezvous with it serves as an allegory of the American relationship with the natural world. That includes how our country originally planted its national identity in the continent’s rarefied natural endowments, then lost its connection to that identity, but now, as the eagle thrives again, it might regain it.

In fact, Isbell’s monumental work is a response to Katrina and the resiliency of our coastal institutions and residents. As a Pulitzer-Prize winning photographer, he chronicled the destruction of the hurricane for The Sun Herald, the Gulfport/Biloxi-based daily newspaper. Isbell explains in his introduction to the The Mississippi Gulf Coast that the work has “special meaning, as it was a therapeutic endeavor after the destruction from Hurricane Katrina.”

In fact, Isbell’s monumental work is a response to Katrina and the resiliency of our coastal institutions and residents. As a Pulitzer-Prize winning photographer, he chronicled the destruction of the hurricane for The Sun Herald, the Gulfport/Biloxi-based daily newspaper. Isbell explains in his introduction to the The Mississippi Gulf Coast that the work has “special meaning, as it was a therapeutic endeavor after the destruction from Hurricane Katrina.”

Cobb’s new book,

Cobb’s new book,

Davis said he wrote The Gulf because he was interested in restoring what he calls “an American sea,” to the conventional historical narrative of America.

Davis said he wrote The Gulf because he was interested in restoring what he calls “an American sea,” to the conventional historical narrative of America.

Such is the wonder and the power of

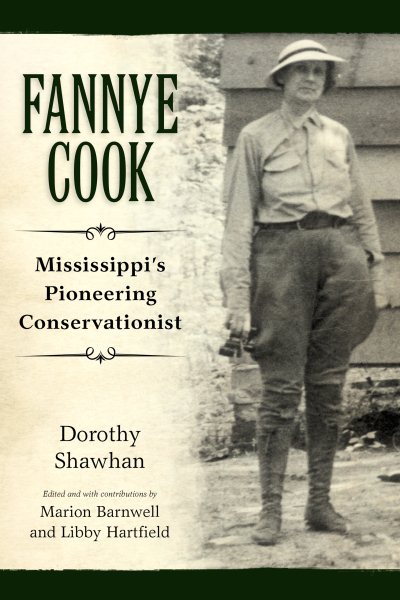

Such is the wonder and the power of  For many outdoors enthusiasts in Mississippi, Dorothy Shawhan’s book

For many outdoors enthusiasts in Mississippi, Dorothy Shawhan’s book

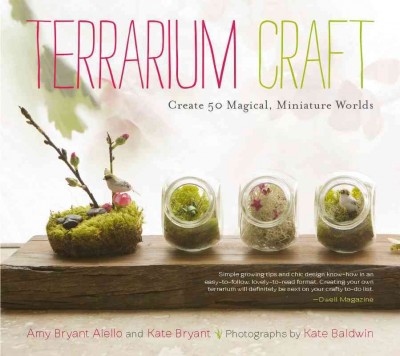

uch always love to make something, but I think the whole new life thing that comes along with spring really does something to me. A book I’ve been drooling over for quite some time now is The Modern Natural Dyer. Not only is it a gorgeous book, but it also tells you how to dye fibers with flowers, vegetables, and spices. Basically head on over to the grocery store and make a mess because I love to make a mess. It’s the cleaning up that presents a problem for me. This book has twenty projects for your home and your wardrobe, including knitting and sewing. Pretty amazing if you think about it. “Oh, why yes, I did make this! I dyed it as well. Eat your freaking heart out!!!” Next up on the docket we have Materially Crafted: A DIY Primer for the Design-Obsessed (that’s me). So this book’s projects are broken down into sections of spray paint, plaster, concrete, paper, thread, wax, wood, and the list goes on. I could definitely get into a modern looking concrete cake stand or some precious wax bud vases. There is more to come about this display, but I feel like I am close to losing all of you so I will leave you here

uch always love to make something, but I think the whole new life thing that comes along with spring really does something to me. A book I’ve been drooling over for quite some time now is The Modern Natural Dyer. Not only is it a gorgeous book, but it also tells you how to dye fibers with flowers, vegetables, and spices. Basically head on over to the grocery store and make a mess because I love to make a mess. It’s the cleaning up that presents a problem for me. This book has twenty projects for your home and your wardrobe, including knitting and sewing. Pretty amazing if you think about it. “Oh, why yes, I did make this! I dyed it as well. Eat your freaking heart out!!!” Next up on the docket we have Materially Crafted: A DIY Primer for the Design-Obsessed (that’s me). So this book’s projects are broken down into sections of spray paint, plaster, concrete, paper, thread, wax, wood, and the list goes on. I could definitely get into a modern looking concrete cake stand or some precious wax bud vases. There is more to come about this display, but I feel like I am close to losing all of you so I will leave you here This year was a doozy. I consumed everything from nonfiction about

This year was a doozy. I consumed everything from nonfiction about