Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (December 1)

Author Phil Keith adds his sixth book to his collection as his collaboration with bestselling writer Tom Clavin unfolds the almost unbelievable story of bravery and valor of a little-known World War I hero in All Blood Runs Red: The Legendary Life of Eugene Bullard–Boxer, Pilot, Soldier, Spy.

Author Phil Keith adds his sixth book to his collection as his collaboration with bestselling writer Tom Clavin unfolds the almost unbelievable story of bravery and valor of a little-known World War I hero in All Blood Runs Red: The Legendary Life of Eugene Bullard–Boxer, Pilot, Soldier, Spy.

Bullard was the first African American military pilot who flew in combat, and the only one to serve as a pilot in World War I. He would later become a jazz musician, a night club owner in Paris, and a spy during the French Resistance.

Among Keith’s previous volumes is Blackhorse Riders, winner of the 2012 award from USA Book News for Best Military Non-Fiction. He was also a finalist for the 2013 Colby Award, and earned a silver medal from the Military Writers Society of America that same year.

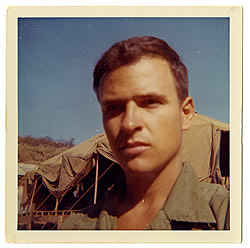

He holds a degree in history from Harvard University, and is a former Navy aviator. During three tours in Vietnam, he was awarded the Purple Heart, Air Medal, Presidential Unit Citation, and the Navy Commendation Medal, among other honors.

Your book states that Eugene Bullard led a “legendary life” as a boxer, pilot, highly decorated soldier, and a spy. Why has his story been so little known?

Phil Keith

Three reasons, primarily: Gene fought for France in World War I, and, of course, he was black. Not many in America, during World War I, were interested in hearing stories about courageous African Americans. The times were still too racially charged, and even the American Air Service had an official policy that banned blacks from serving.

Secondly, all during his World War I experiences, he was constantly badgered and put down by a particularly racist American living in Paris, Dr. Edmund Gros. This doctor was the founder of the famed American Ambulance Service and co-founder of what became the Lafayette Flying Corps. He was a virulent hater of blacks, and of Gene in particular, because Bullard had been so successful despite Gros’ best efforts to ground him. Gros constantly omitted his name from recognition of Americans helping in the war effort and eventually was successful in getting Gene bounced out of French aviation.

Thirdly, when Gene returned to America, he wrote his autobiography in the late 1950s. That was at a time when Franco-American relations were at a low ebb; and, the editors who reviewed his manuscript thought it was too fantastical to be true, especially for a barely educated black man.

How did you hear about Bullard, and how did you handle the research for this book, working with information that was not only hard to find, but often conflicting?

Doing research for a book on World War I, with a chapter on America’s famous aviators, I came across a footnote in some Eddie Rickenbacker material that mentioned Bullard. That was the first I had ever heard of him. I was fascinated and began to dig.

I found the only existing archive on Bullard at Columbus State University in his hometown of Columbus, Ga. I spent a week combing through their boxes. We also found bits and pieces of the Bullard story in other bios, particularly his famous contemporaries.

And, yes, there were conflicting stories, so we had to set up a rigorous process of “triangulation:” Nothing got in the book unless it could be confirmed by at least two other sources.

Despite the obstacles, why did you and your co-author Tom Clavin believe Bullard’s story needed to be told?

Bullard is clearly one of the most fascinating historical figures of the 20th century yet very few people know about him; so, from that standpoint alone, his story is important–fills in a missing piece. Perhaps even more importantly, Bullard’s story should be a role model for today’s African American young men and women. He is a true hero who can be looked up to and his examples of determination and persistence are crucial, we think, to the telling of the experiences of post-slavery blacks in America and Europe.

How did you two split up the writing of this book?

Tom is a dogged researcher, so he got the task of “story-hound,” except for the sojourn to Georgia. Much of the original sleuthing went to Tom. We also wrote to our individual strengths: I concentrated on the military aspects of Gene’s life, for example, and Tom, who has written several sports books, did the work on Gene’s boxing days. I did most of the rough draft manuscript, and Tom did the vast majority of the editing and smoothing. I had never done a collaboration before, but Tom has. I have to say it went very smoothly. It was so smooth, in fact, that our editor at Hanover Square Press immediately optioned our next book idea, which is in progress now. It will be a ripping good sea story about the Civil War’s most famous sea battle between the USS Kearsarge and the CSS Alabama.

Please share the story of how the title of this book was chosen.

“All Blood Runs Red” is the Anglicized version of the French “Tous Sange Que Coule C’est Rouge.” This was the motto Bullard had stenciled on the sides of his SPAD fighter plane, with the words surrounding a large red heart with a dagger stuck in it. For Bullard, he wanted to make the point that “we’re all in this (the war) together.” It did not matter the color of any man’s skin: when any soldier bled, all the blood was red. This was also the title of his never published autobiography (1960) and we wanted to use it in his honor.

Phil Keith will at Lemuria on Tuesday, December 3, at 5:00 p.m. to sign copies of and discuss All Blood Runs Red. Lemuria has selected All Blood Runs Red its December 2019 selection for its First Editions Club for Nonfiction.

And yet. As Hungary and the citizens of the Engels’ town of Pecs, Hungary were overrun by Nazi forces in 1944, a century of prominence, good works and assumed assimilation weren’t enough for the Engels. The scion of the Pecs branch of the family—McMullan’s grandfather’s first cousin Richard Engel—died at the Mauthausen concentration camp after being rounded up along with other town Jews in March 1944. The story of Richard’s descent from respected, wealthy World War I war hero and city civic leader to being marched off as townspeople watched is the spellbinding story that McMullan tells in

And yet. As Hungary and the citizens of the Engels’ town of Pecs, Hungary were overrun by Nazi forces in 1944, a century of prominence, good works and assumed assimilation weren’t enough for the Engels. The scion of the Pecs branch of the family—McMullan’s grandfather’s first cousin Richard Engel—died at the Mauthausen concentration camp after being rounded up along with other town Jews in March 1944. The story of Richard’s descent from respected, wealthy World War I war hero and city civic leader to being marched off as townspeople watched is the spellbinding story that McMullan tells in

That curiosity eventually led to published research in newspapers, magazine, website, and blogs about the role of women in the Civil War.

That curiosity eventually led to published research in newspapers, magazine, website, and blogs about the role of women in the Civil War.

The author’s newest book,

The author’s newest book,

Though lesser known than other heroic military campaigns throughout America’s history, the struggle that played out along the frozen shores of the Chosin Reservoir in the snowy mountains of North Korea in 1950 tested the mettle of the First Marine Division beyond reason.

Though lesser known than other heroic military campaigns throughout America’s history, the struggle that played out along the frozen shores of the Chosin Reservoir in the snowy mountains of North Korea in 1950 tested the mettle of the First Marine Division beyond reason.

As a Francophile graphic designer who spends most of her reading time studying World War II,

As a Francophile graphic designer who spends most of her reading time studying World War II,

The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1945. The United States was caught virtually unawares, in a nearly two decade season of disarmament. The U.S. military had sparse forces, and few spies abroad. There was an immediate and urgent need for code breakers to decipher enemy message systems.

The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1945. The United States was caught virtually unawares, in a nearly two decade season of disarmament. The U.S. military had sparse forces, and few spies abroad. There was an immediate and urgent need for code breakers to decipher enemy message systems.

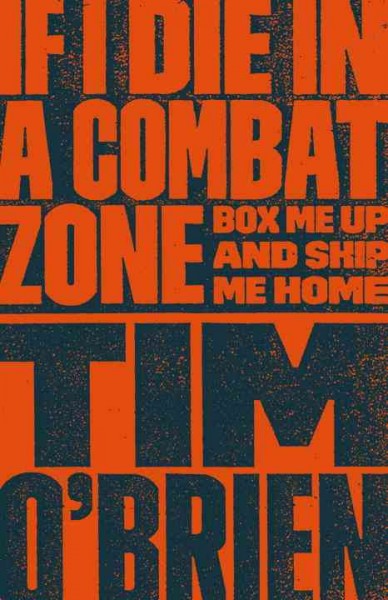

This book is tough; it has a way of making the reader feel many, sometimes awful, feelings. This book is told in stories, through characters, and simply with O’Brien’s very own thoughts and opinions. He encountered some truly horrible people and situations and he does not hold back at all, immersing the reader as much as he can in the horrors and realities of war.

This book is tough; it has a way of making the reader feel many, sometimes awful, feelings. This book is told in stories, through characters, and simply with O’Brien’s very own thoughts and opinions. He encountered some truly horrible people and situations and he does not hold back at all, immersing the reader as much as he can in the horrors and realities of war.