By Lisa Newman. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (July 15)

“If you want to buy, I’m your chap!” was the cry of peddler at the market, on the street corner, or door-to-door in country towns.

The term “chap” comes from the Old English céap, meaning “to deal, barter, or do business”. These chapmen sold all kinds of things, but they were known for books made for cheap distribution called chapbooks. One of the most famous chapbooks in the United States is Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” (January 1776), considered to be the single most important piece of writing to influence the declaration of independence.

Anti-establishment groups of the modern era have also employed the utility of the chapbook.

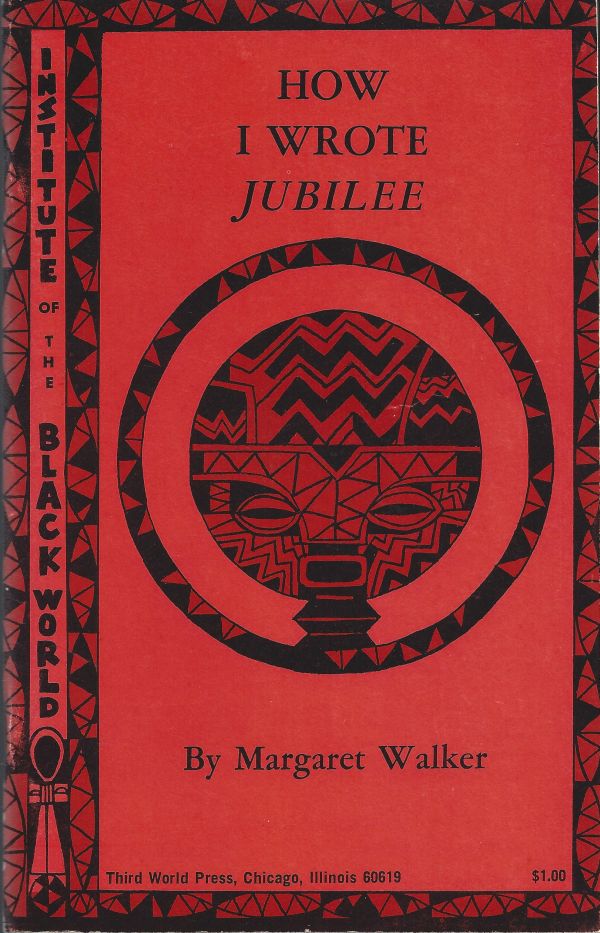

In the 1950s, the Beats adopted the form to publish poetry, most famously “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg and issued by Lawrence Ferlinghetti of City Lights books in San Francisco. The Pocket Poet Series introduced avant-garde poetry to the masses and is still in print today. Broadside Press in Detroit supported the writers of the civil rights movement, publishing Margaret Walker’s “Prophets for a New Day” (1970) and “October Journey” (1973) in addition to works by Alice Walker and Nikki Giovanni.

In the 1950s, the Beats adopted the form to publish poetry, most famously “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg and issued by Lawrence Ferlinghetti of City Lights books in San Francisco. The Pocket Poet Series introduced avant-garde poetry to the masses and is still in print today. Broadside Press in Detroit supported the writers of the civil rights movement, publishing Margaret Walker’s “Prophets for a New Day” (1970) and “October Journey” (1973) in addition to works by Alice Walker and Nikki Giovanni.

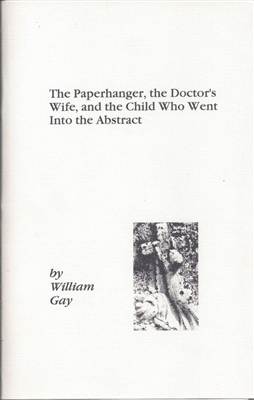

Small literary presses have adopted the form as an inexpensive way to promote unknown writers. These chapbooks might include one short story or an excerpt from an upcoming novel. The first publication by William Gay, the late Southern Gothic writer from Hohenwald, Tennessee, was a chapbook titled “The Paperhanger, the Doctor’s Wife, and the Child Who Went into the Abstract” (Book Source Press, 1998). Limited to a print run of 250 and signed by Gay, this short story chapbook is a fine example of a collectible literary debut. Other presses have used the chapbook as a way to celebrate the success of an established literary writer.

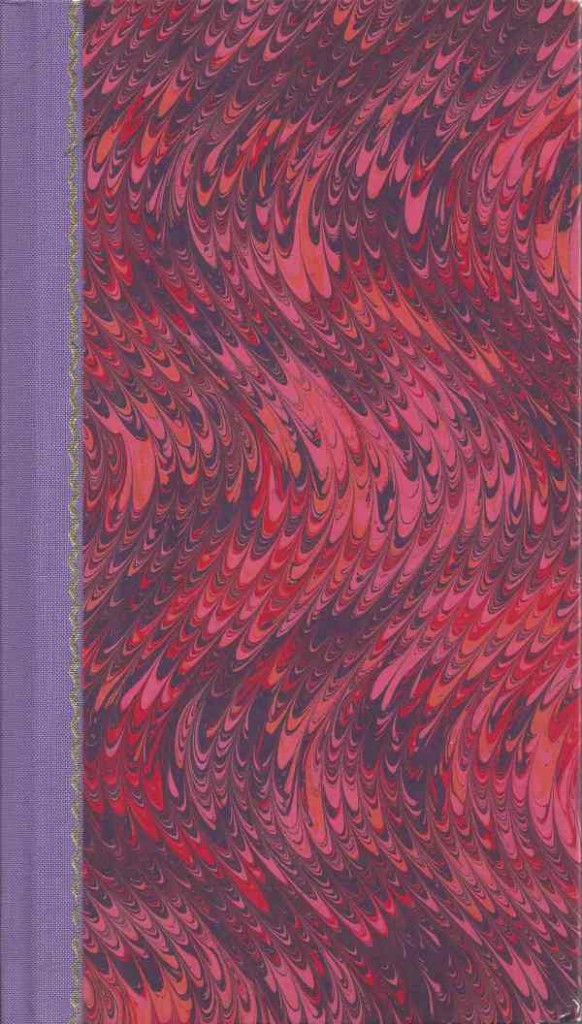

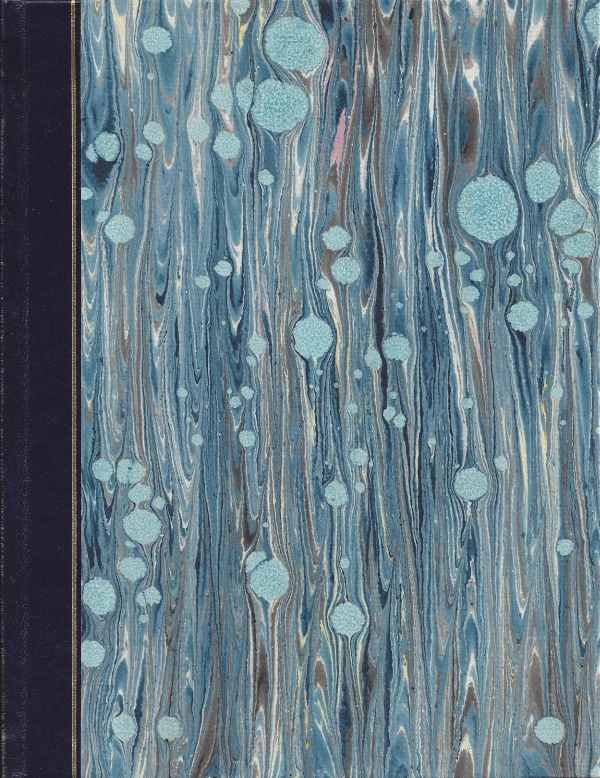

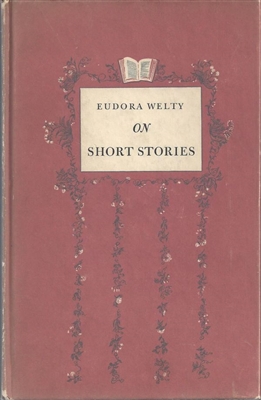

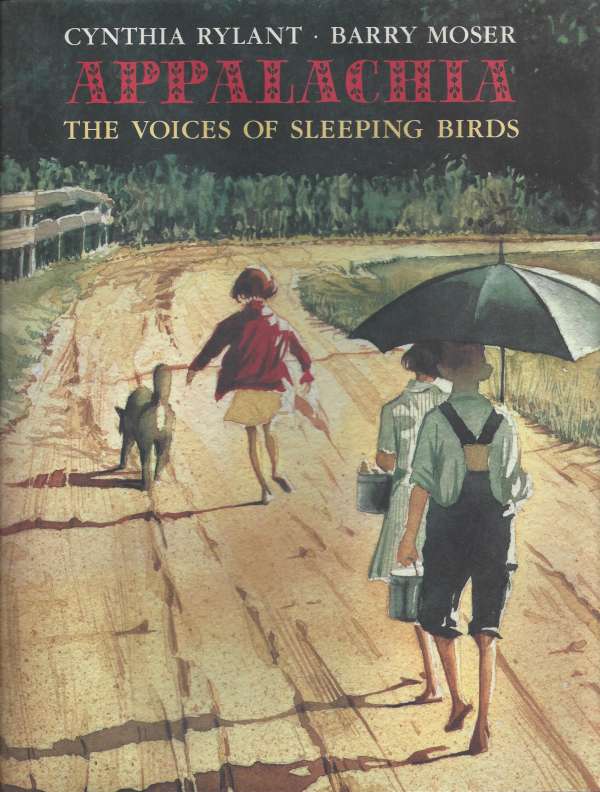

John Updike’s “The Women Who Got Away” (William B. Ewert, 1998) is an example of an embellished chapbook illustrated with woodcuts by Barry Moser. “Gwinlan’s Harp” by Ursula K. Le Guin (Lord John Press, 1981) and “Black Butterfly” by Barry Hannah (Nouveau Press, 1982) are beautiful examples of decorative hand-made paper and hand-stitched binding. All of these books were issued in limited number and signed by the author. “On Short Stories” by Eudora Welty (Harcourt Brace, 1949) was issued in decorative boards as a celebration of the short story and as a Christmas holiday memento.

John Updike’s “The Women Who Got Away” (William B. Ewert, 1998) is an example of an embellished chapbook illustrated with woodcuts by Barry Moser. “Gwinlan’s Harp” by Ursula K. Le Guin (Lord John Press, 1981) and “Black Butterfly” by Barry Hannah (Nouveau Press, 1982) are beautiful examples of decorative hand-made paper and hand-stitched binding. All of these books were issued in limited number and signed by the author. “On Short Stories” by Eudora Welty (Harcourt Brace, 1949) was issued in decorative boards as a celebration of the short story and as a Christmas holiday memento.

Some people think that the chapbook has evolved into online blogs. However, as the internet has become common and screen fatigue a daily headache, the physical chapbook could be revitalized. The handmade papers, the attention to detail heightens the tactile pleasure and the desire to add a rare book from a favorite author to your bookshelf. The number of books and classes on handcrafting books has also increased with poets publishing their own books they call zines.

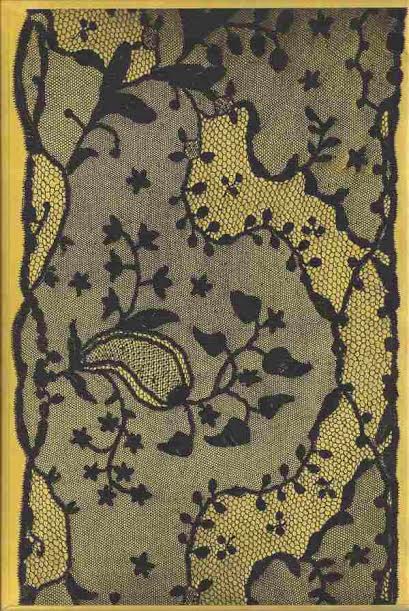

At the time “Love in the Time of Cholera” was published in the United States in 1988, García Márquez could not tour in the United States because of the government travel ban, so Random House mailed the sheets to García Márquez for him to sign. The sheets were bound into a beautiful limited edition of 350 copies with pink cloth over black cloth boards with a black lace patterned acetate jacket, housed in a yellow slipcase with a black lace pattern.

At the time “Love in the Time of Cholera” was published in the United States in 1988, García Márquez could not tour in the United States because of the government travel ban, so Random House mailed the sheets to García Márquez for him to sign. The sheets were bound into a beautiful limited edition of 350 copies with pink cloth over black cloth boards with a black lace patterned acetate jacket, housed in a yellow slipcase with a black lace pattern.

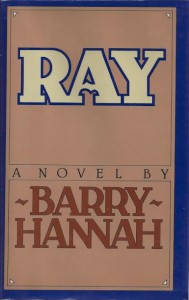

This fragment of “Ray” also differs from the complete version of “Ray” published by Knopf in 1980 as pages 12-26. The publication of Gorgas Oak’s “Neighborhood” provides a rare opportunity to compare an early draft of a literary text with its final form.

This fragment of “Ray” also differs from the complete version of “Ray” published by Knopf in 1980 as pages 12-26. The publication of Gorgas Oak’s “Neighborhood” provides a rare opportunity to compare an early draft of a literary text with its final form.

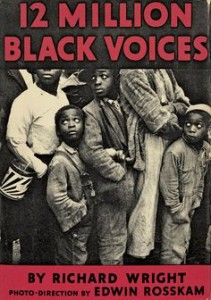

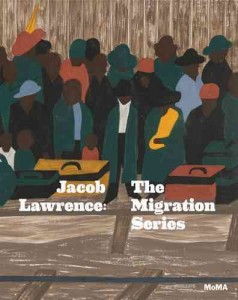

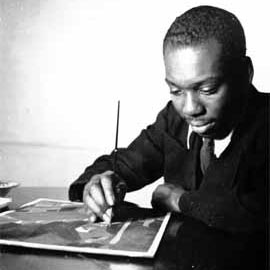

Jacob Lawrence was not your typical painter. He often spent months at a branch of the New York Public Library, taking notes from journals and books and other documents before he would began work on a formal painting project. Lawrence wanted his art to teach history to his people. In describing his research efforts for The Great Migration, Lawrence remarked:

Jacob Lawrence was not your typical painter. He often spent months at a branch of the New York Public Library, taking notes from journals and books and other documents before he would began work on a formal painting project. Lawrence wanted his art to teach history to his people. In describing his research efforts for The Great Migration, Lawrence remarked: