By Lisa Newman. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (July 15)

“If you want to buy, I’m your chap!” was the cry of peddler at the market, on the street corner, or door-to-door in country towns.

The term “chap” comes from the Old English céap, meaning “to deal, barter, or do business”. These chapmen sold all kinds of things, but they were known for books made for cheap distribution called chapbooks. One of the most famous chapbooks in the United States is Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” (January 1776), considered to be the single most important piece of writing to influence the declaration of independence.

Anti-establishment groups of the modern era have also employed the utility of the chapbook.

In the 1950s, the Beats adopted the form to publish poetry, most famously “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg and issued by Lawrence Ferlinghetti of City Lights books in San Francisco. The Pocket Poet Series introduced avant-garde poetry to the masses and is still in print today. Broadside Press in Detroit supported the writers of the civil rights movement, publishing Margaret Walker’s “Prophets for a New Day” (1970) and “October Journey” (1973) in addition to works by Alice Walker and Nikki Giovanni.

In the 1950s, the Beats adopted the form to publish poetry, most famously “Howl” by Allen Ginsberg and issued by Lawrence Ferlinghetti of City Lights books in San Francisco. The Pocket Poet Series introduced avant-garde poetry to the masses and is still in print today. Broadside Press in Detroit supported the writers of the civil rights movement, publishing Margaret Walker’s “Prophets for a New Day” (1970) and “October Journey” (1973) in addition to works by Alice Walker and Nikki Giovanni.

Small literary presses have adopted the form as an inexpensive way to promote unknown writers. These chapbooks might include one short story or an excerpt from an upcoming novel. The first publication by William Gay, the late Southern Gothic writer from Hohenwald, Tennessee, was a chapbook titled “The Paperhanger, the Doctor’s Wife, and the Child Who Went into the Abstract” (Book Source Press, 1998). Limited to a print run of 250 and signed by Gay, this short story chapbook is a fine example of a collectible literary debut. Other presses have used the chapbook as a way to celebrate the success of an established literary writer.

John Updike’s “The Women Who Got Away” (William B. Ewert, 1998) is an example of an embellished chapbook illustrated with woodcuts by Barry Moser. “Gwinlan’s Harp” by Ursula K. Le Guin (Lord John Press, 1981) and “Black Butterfly” by Barry Hannah (Nouveau Press, 1982) are beautiful examples of decorative hand-made paper and hand-stitched binding. All of these books were issued in limited number and signed by the author. “On Short Stories” by Eudora Welty (Harcourt Brace, 1949) was issued in decorative boards as a celebration of the short story and as a Christmas holiday memento.

John Updike’s “The Women Who Got Away” (William B. Ewert, 1998) is an example of an embellished chapbook illustrated with woodcuts by Barry Moser. “Gwinlan’s Harp” by Ursula K. Le Guin (Lord John Press, 1981) and “Black Butterfly” by Barry Hannah (Nouveau Press, 1982) are beautiful examples of decorative hand-made paper and hand-stitched binding. All of these books were issued in limited number and signed by the author. “On Short Stories” by Eudora Welty (Harcourt Brace, 1949) was issued in decorative boards as a celebration of the short story and as a Christmas holiday memento.

Some people think that the chapbook has evolved into online blogs. However, as the internet has become common and screen fatigue a daily headache, the physical chapbook could be revitalized. The handmade papers, the attention to detail heightens the tactile pleasure and the desire to add a rare book from a favorite author to your bookshelf. The number of books and classes on handcrafting books has also increased with poets publishing their own books they call zines.

Karl Marlantes found a publisher in El Léon Literary Arts, a small press privately funded through donations. Led by author Thomas Farber, the operation is known to run on a $200 a year travel and entertainment budget and publishes literary works that might not seem commercially viable by mainstream publishers. By the time the 700-page Matterhorn was printed in softcover and review copies were sent out, a group of booksellers got the attention of El Léon by submitting Matterhorn to a first-novel contest. Soon Farber began getting calls from larger publishers. Eventually, a deal with the independent press Grove Atlantic was made and Matterhorn was released in hardback in 2010. Behind the scenes, Grove Atlantic’s Morgan Entrekin championed Matterhorn to booksellers across the country. The success of Matterhorn is due to the perseverance of its author, small presses, and the diligence of booksellers. It is a story of authenticity as opposed to overblown media hype.

Karl Marlantes found a publisher in El Léon Literary Arts, a small press privately funded through donations. Led by author Thomas Farber, the operation is known to run on a $200 a year travel and entertainment budget and publishes literary works that might not seem commercially viable by mainstream publishers. By the time the 700-page Matterhorn was printed in softcover and review copies were sent out, a group of booksellers got the attention of El Léon by submitting Matterhorn to a first-novel contest. Soon Farber began getting calls from larger publishers. Eventually, a deal with the independent press Grove Atlantic was made and Matterhorn was released in hardback in 2010. Behind the scenes, Grove Atlantic’s Morgan Entrekin championed Matterhorn to booksellers across the country. The success of Matterhorn is due to the perseverance of its author, small presses, and the diligence of booksellers. It is a story of authenticity as opposed to overblown media hype. This authenticity leads to a collectible book. The copies of Matterhorn printed in softcover at El Léon became advanced copies for Grove Atlantic’s hardcover edition. For collectors, that softcover is the true first edition. Matterhorn follows in the tradition of other great war novels like Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and James Jones’ The Thin Red Line.

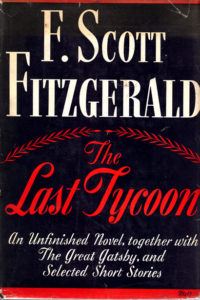

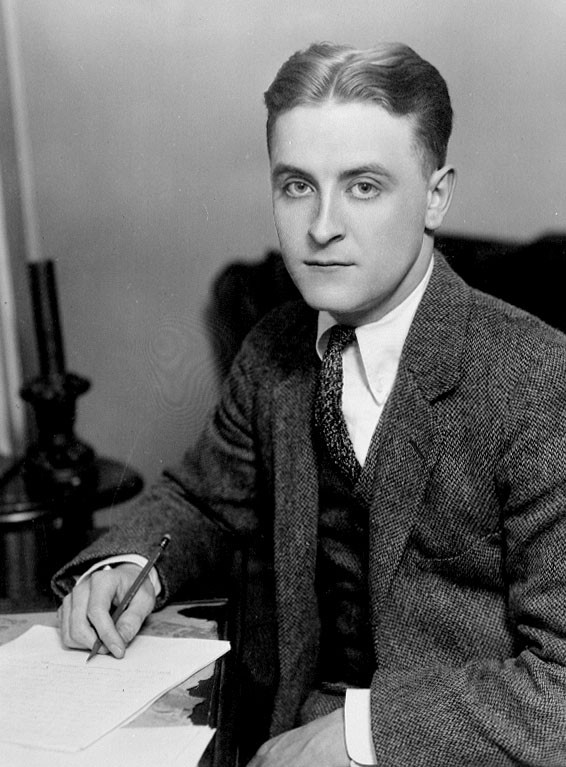

This authenticity leads to a collectible book. The copies of Matterhorn printed in softcover at El Léon became advanced copies for Grove Atlantic’s hardcover edition. For collectors, that softcover is the true first edition. Matterhorn follows in the tradition of other great war novels like Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead and James Jones’ The Thin Red Line. After his death in 1940, a longtime critic and friend Edmund Wilson secured permission from Fitzgerald’s family to publish “The Last Tycoon.” Wilson had never held back his negative criticism of the author’s work, even from Fitzgerald’s beginnings when Wilson published a satirical poem arguing that the young writer’s work was shallow and superficial. But Wilson was deeply affected by his death, expressing in a letter to Fitzgerald’s wife, Zelda: “I feel myself as though I had been suddenly robbed of some part of my own personality.”

After his death in 1940, a longtime critic and friend Edmund Wilson secured permission from Fitzgerald’s family to publish “The Last Tycoon.” Wilson had never held back his negative criticism of the author’s work, even from Fitzgerald’s beginnings when Wilson published a satirical poem arguing that the young writer’s work was shallow and superficial. But Wilson was deeply affected by his death, expressing in a letter to Fitzgerald’s wife, Zelda: “I feel myself as though I had been suddenly robbed of some part of my own personality.” Wilson, who must have felt some regret at being so critical of what he often called a “commercial” and “trashy” writer, decided to set the tone for Fitzgerald’s legacy by preparing his last manuscript and titling it “The Last Tycoon.” It would be published in book form accompanied strategically by “The Great Gatsby” and selected short stories. In the Foreword, Wilson announced “The Last Tycoon” to be “Fitzgerald’s most mature piece of work” and “the best novel we have had about Hollywood.” Other critics followed with similar praise. Novelist J. F. Powers asserted that “The Last Tycoon” contained more of his best writing than anything he had ever done and Fitzgerald’s best had always been the best there was.”

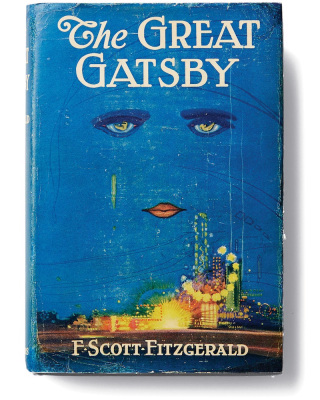

Wilson, who must have felt some regret at being so critical of what he often called a “commercial” and “trashy” writer, decided to set the tone for Fitzgerald’s legacy by preparing his last manuscript and titling it “The Last Tycoon.” It would be published in book form accompanied strategically by “The Great Gatsby” and selected short stories. In the Foreword, Wilson announced “The Last Tycoon” to be “Fitzgerald’s most mature piece of work” and “the best novel we have had about Hollywood.” Other critics followed with similar praise. Novelist J. F. Powers asserted that “The Last Tycoon” contained more of his best writing than anything he had ever done and Fitzgerald’s best had always been the best there was.” Fitzgerald’s influence, his attention to the illusive American dream, is seen in the work of Richard Yates, J. D. Salinger, Joseph Heller, and many contemporary writers. Mystery writer, Raymond Chandler, wrote that that “Fitzgerald is a subject no one has the right to mess up . . . He had one of the rarest qualities in all of literature . . . The word is charm—charm as Keats would have used it . . . It’s a kind of subdued magic, controlled and exquisite.” While Fitzgerald had sold less than 25,000 copies of “The Great Gatsby” at the time of his death, this book has now sold over 25 million copies worldwide.

Fitzgerald’s influence, his attention to the illusive American dream, is seen in the work of Richard Yates, J. D. Salinger, Joseph Heller, and many contemporary writers. Mystery writer, Raymond Chandler, wrote that that “Fitzgerald is a subject no one has the right to mess up . . . He had one of the rarest qualities in all of literature . . . The word is charm—charm as Keats would have used it . . . It’s a kind of subdued magic, controlled and exquisite.” While Fitzgerald had sold less than 25,000 copies of “The Great Gatsby” at the time of his death, this book has now sold over 25 million copies worldwide.

After the great success of his first novel,

After the great success of his first novel,  F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote his first novel,

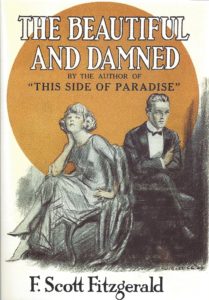

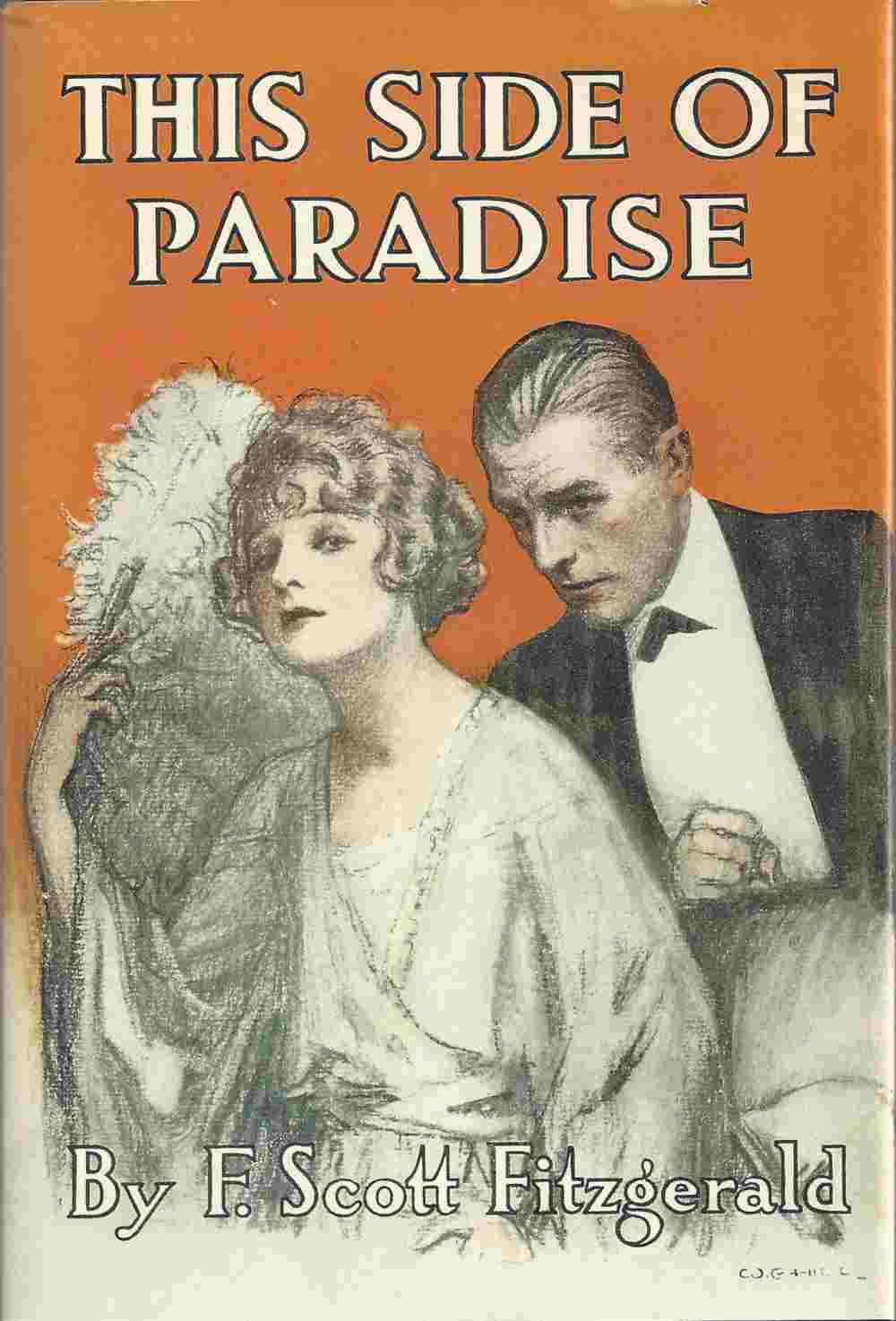

F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote his first novel,  The dust jacket of any Fitzgerald first edition is key to its value. In the 1920s, publishers had only been making dust jackets for a short time. Readers often pulled them off and threw them away. Prior to the advent of the dust jacket, books were stamped with the title and author and often embellished with beautiful designs and gold stamped accents. The new dust jackets promoted the book, protected it, and advertised other books from the publisher. Because of this change in book design, it is very hard to find one of the 3,000 first printings of “This Side of Paradise”—a debut by a relatively unknown author—with the dust jacket present and in good condition. The era before climate control also did nothing to help preserve books.

The dust jacket of any Fitzgerald first edition is key to its value. In the 1920s, publishers had only been making dust jackets for a short time. Readers often pulled them off and threw them away. Prior to the advent of the dust jacket, books were stamped with the title and author and often embellished with beautiful designs and gold stamped accents. The new dust jackets promoted the book, protected it, and advertised other books from the publisher. Because of this change in book design, it is very hard to find one of the 3,000 first printings of “This Side of Paradise”—a debut by a relatively unknown author—with the dust jacket present and in good condition. The era before climate control also did nothing to help preserve books.