Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (February 4)

As an Army brat who swore in her teen years that she’d never live in Mississippi, poet and University of Mississippi professor Ann Fisher-Wirth has, after nearly 30 years as an Oxford resident, decided that Mississippi (along with parts of California) now feels like home.

Not only has she felt moved to compose poetry honoring Mississippi’s culture, history, and people, but she is devoted to preserving its land, which she believes has suffered “severe environmental degradation that cannot be separated from its history of poverty and racial oppression.”

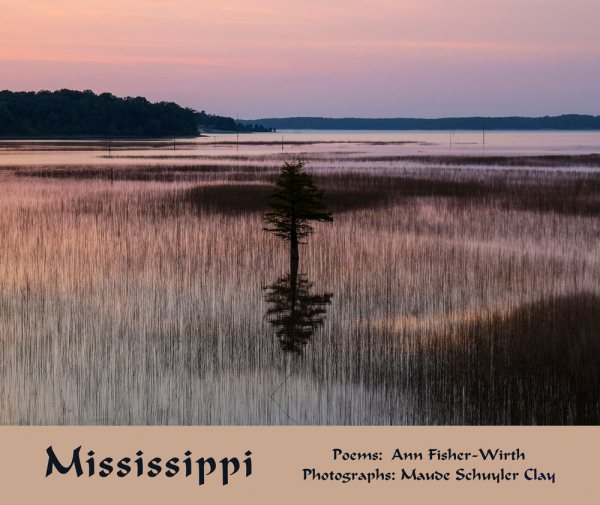

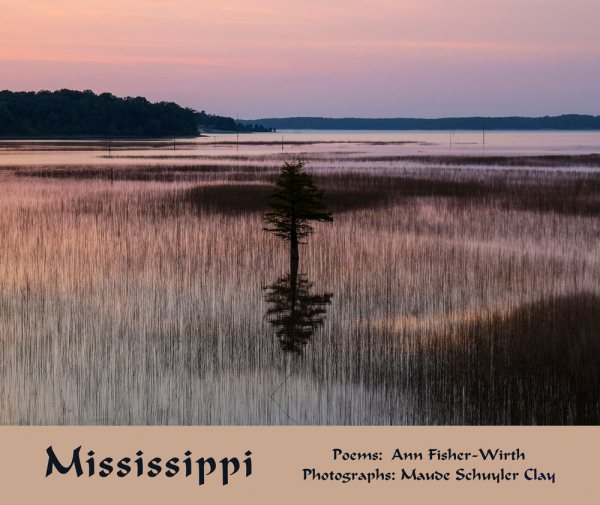

Her newest book, titled Mississippi, is a collaboration with acclaimed photographer and Delta native Maude Schuyler Clay, offering a different perspective on her current home state–one that is both visual and literary. The volumes includes 47 sets of Clay’s striking–and sometimes haunting–photos, each paired with one of Fisher-Wirth’s reflective poems.

Her newest book, titled Mississippi, is a collaboration with acclaimed photographer and Delta native Maude Schuyler Clay, offering a different perspective on her current home state–one that is both visual and literary. The volumes includes 47 sets of Clay’s striking–and sometimes haunting–photos, each paired with one of Fisher-Wirth’s reflective poems.

Photographs and letterpress poems from this project are on exhibit throughout Mississippi, and a performance piece involving six actors has been created from two dozen of the poems.

Fisher-Wirth’s other poetry books include Dream Cabinet, Carta Marina, Five Terraces, and Blue Window. She has alos published an academic book on William Carlos Williams and four poetry chapbooks. With Laura-Gray Street, she co-edited the groundbreaking Ecopoetry Anthology.

She has been the recipient of several residencies, is a Fellow of the Black Earth Institute, and received a senior Fulbright to Switzerland and a Fulbright Distinguished Chair award to Sweden. She is also a past president of the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment. Fisher-Wirth teaches American literature and poetry workshops and directs the Environmental Studies program at Ole Miss. She has recently completed a sixth poetry book manuscript, Because Here We Are.

There was a time when you swore you’d never live here. Tell me about your Mississippi experience, and why you’ve stayed.

I was an Army brat; when I was 10, my father retired and my family moved to Berkeley, California, where I spent my teenage years. Living in Berkeley in the 1960s, I paid careful attention to the civil rights movement; that’s why I swore I’d never live in Mississippi. I lived in southern California, Belgium, and Virginia.

Ann Fisher-Wirth

But in the late 1980s, we cam here (to Ole Miss), lured by the terrific English department, the literary community centered in Square Books, and the fact that Mississippi seemed to be a very complicated, culturally fascinating, beautiful and troubled place. We came in a spirit of adventure, and a feeling that we could do good work here. We’ve stayed because we want to. The English department has just gotten better and better–it’s a friendly and increasingly heterogeneous department. I love working with our MFA poets as well as with the undergraduates who study American literature and creative nonfiction with me. I also love directing and teaching for the minor in Environmental Studies, and ahve had some fantastic, dynamic students over the years.

Our children are all grown–our three daughters live elsewhere, but our two sons are here, as are two of our grandchildren–a major attraction. I’m attached to our house, old and drafty as it is. And Oxford is just plain an incredible place to be a writer.

How did you and Maude come up with the idea to create a book together? Were the poems written to go with the photographs, or were the photographs taken to go with the poems?

Maude Schuyler Clay

Maude and I have known each other socially for decades and have known each other’s work. At one point or the other of us casually remarked, “We should do something sometime.” She thinks I was the one; I think she was the one.

A few years ago she started sending me photographs she had taken but never published. I had recently published Dream Cabinet and The Ecopoetry Anthology and was looking for a new project. I was moved by her photo of a tree in water–this has turned out to be the cover image for the book–and I wrote the poem based on the yoga pose Vrksasana that begins “You stand in Tree…” A little later, she sent me a hauntingly beautiful image of a boat in greenish water. I knew I wanted to write a poem based on this photo, but had no idea what it could say until Made mentioned that the boat had belonged to her close friend who had just died. Immediately, the poem “Between two worlds / the soul floats…” came to me, and eventually that became the opening poem of the book. Others followed as Maude continued to send me photographs over the next couple of years.

Nearly all the poems were written to go with photographs; in only on or two cases, we found photos to go with poems I had already written. But as you know, the poems don’t just describe the photographs, and, with one exception, the photographs don’t have people in them.

Instead, the poems are spoken in voices of fictive characters that the photographs somehow suggested to me. Creating this book was, for me, very much an act of channeling voices, scraps of lives that I have encountered since living in Mississippi, sometimes combined with scraps of memory from my own life–exploring the incredible richness of this region’s spoken language.

What is the message of the blending of this poetry with the sometimes bare, sometimes harsh images of the state’s landscape, that you want to leave with your readers?

Poems are more about experiences than messages, so I don’t really have a message per se. I wanted the poems to reflect the variety of voices, and hence the variety of people, in Mississippi: old, young; wise, foolish; poor, middle-class, wealthy; loving, hateful; male, female; lettered, unlettered; black, white, Native American. Some of the poems are harsh and bleak, and speak to the realities of racism, poverty, violence, and environmental damage that are part of Mississippi. Others are lush and beautiful, as befits the beauty and gentler aspects of the people and places.

How did you develop an interest in writing poetry–and then realize that you were so good at it?

I come from a family of English teachers and readers, and I’ve always wanted to write poetry. I wrote a little bit in high school, then stopped, then wrote a little bit more while writing my dissertation, then stopped. Until I got tenure at the University of Mississippi, my writing was academic–a book on William Carlos Williams, a numbers of essays on Williams, Willa Cather, Anita Brookner, Robert Haas, and others.

Then just for fun I audited a poetry workshop that my friend Aleda Shirley was teaching, and after the first day, I said to myself, “This is it. I’m writing poems from now on, and never looking back.” Some time later, I attended a week-long workshop in California called The Art of the Wild, and wrote a poem called, “What Is There to Do in Mississippi?” It became my first published poem, in the magazine The Wilderness Society, and it even paid–so I took my whole family out to dinner to celebrate at City Grocery (in Oxford). After that, it took a while to get my first book, Blue Window, published, and the rest has followed. It’s always a a lot of work, always an adventure.

Thank you for saying I am “so good at it.” I sure love it. I’ve always loved writing, but my confidence about it is never a steady-state thing.

Your poetry style here is at once stark and powerful–there are no titles, no punctuation, no apparent patter of wordplay–and grammatical rules are cast aside. Tell me how this design contributes to the interpretation of the poetry.

I wanted to get rid of the conventional accouterments of poetry and just let the voices be heard. I also wanted the eye to be alive on the page–to treat the page as a field of composition and make use of negative space in order to capture the way we actually speak, which is never a steady march forward, and never completely grammatically. One of the strongest elements of Southern literature is its orality, and I wanted to honor the living voices in every way.

There are several recurring themes in your poetry in this book: racism, sexual desire, death, family, tragedy, memories, and nature’s beauty and fury. Why these topics?

Is there anything else? I’m partly kidding. But a writer doesn’t exactly get to choose his or her themes; these are topics that have greatly concerned me my whole life. They’re central to human experience, no matter where or when. By the way, I love the phrase “nature’s beauty and fury.” That “fury” is so important.

Do you have plans for future writing projects?

Well, I have a lot of uncollected poems and a desire to create another book, but as yet it has no shape. I’m writing new poems all the time, some of which are worth keeping. For the pas two fall semesters, I have team-taught with my colleague Patrick Alexander in the Prison to College Pipeline program for pre-release prisoners at Parchman. This has been an intensely rich experience for me and I’ve been writing about that. And there are a couple of editing projects I’ll be working on–but it’s too early to talk about them.

Ann Fisher-Wirth and Maude Schuyler Clay will be at Lemuria on Friday, February 9, at 5:00 to sign and discuss their new book, Missisippi.

So plays out the message in Julie Cantrell’s latest novel, Perennials (Thomas Nelson), an intimate and intriguing look at families, relationships, and the role each member plays. The New York Times and USA Today award-winning author is known for her inspirational novels that offer hope in the face of emotional issues. Her smooth, lyrical writing style fits well with the laid-back atmosphere of Southern living.

So plays out the message in Julie Cantrell’s latest novel, Perennials (Thomas Nelson), an intimate and intriguing look at families, relationships, and the role each member plays. The New York Times and USA Today award-winning author is known for her inspirational novels that offer hope in the face of emotional issues. Her smooth, lyrical writing style fits well with the laid-back atmosphere of Southern living.

Newlyweds Celestial and Roy drive from their home in Atlanta to visit Roy’s parents in Eloe, Louisiana. Tension between Celestial and her mother-in-law makes the young couple decide to rent a hotel room rather than stay at the house. At the hotel, an argument between the couple sends Roy out of their room for less than an hour, an hour that will determine the course of both of their lives.

Newlyweds Celestial and Roy drive from their home in Atlanta to visit Roy’s parents in Eloe, Louisiana. Tension between Celestial and her mother-in-law makes the young couple decide to rent a hotel room rather than stay at the house. At the hotel, an argument between the couple sends Roy out of their room for less than an hour, an hour that will determine the course of both of their lives. Perhaps others among you received a more comprehensive education at your own schooling or by your own volition, but for anybody who considers themselves a true Jacksonian, I cannot recommend highly enough Josh Foreman and Ryan Starrett’s

Perhaps others among you received a more comprehensive education at your own schooling or by your own volition, but for anybody who considers themselves a true Jacksonian, I cannot recommend highly enough Josh Foreman and Ryan Starrett’s

Her newest book, titled

Her newest book, titled

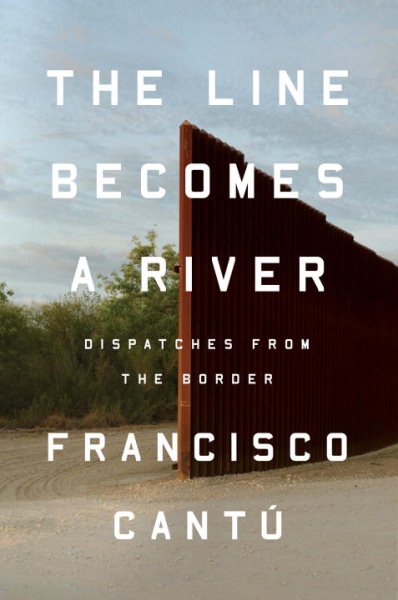

One such conversation I feel like I’m not that knowledgeable about is immigration. I hear a lot of things, but haven’t really tried reading about the topic myself. So when The Line Becomes a River fell into my hands, I knew it was a chance for me to start listening to that conversation more closely.

One such conversation I feel like I’m not that knowledgeable about is immigration. I hear a lot of things, but haven’t really tried reading about the topic myself. So when The Line Becomes a River fell into my hands, I knew it was a chance for me to start listening to that conversation more closely.

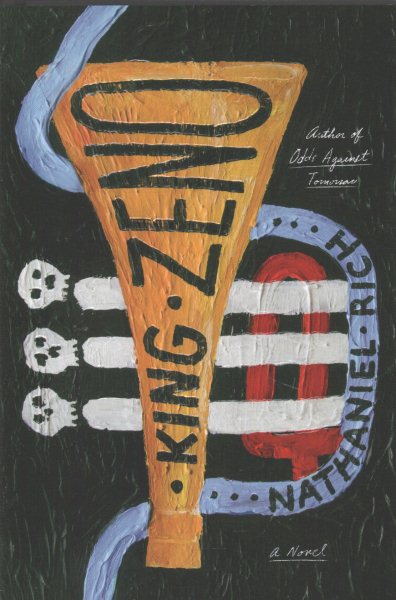

The initial idea grew out of my fascination with two historical events: the series of unsolved ax murders that reached its culmination with a bizarre letter to the Times-Picayune; and the excavation of the Industrial Canal, a hubristic manhandling of the local terrain that has haunted New Orleans ever since.

The initial idea grew out of my fascination with two historical events: the series of unsolved ax murders that reached its culmination with a bizarre letter to the Times-Picayune; and the excavation of the Industrial Canal, a hubristic manhandling of the local terrain that has haunted New Orleans ever since.

I believe each of them is stronger than he initially thinks is the aftermath of that tragedy. Richard is a naturally skilled writer, and those abilities, along with a lifetime of trying to do an honest job as a reporter, eventually re-involve him in life.

I believe each of them is stronger than he initially thinks is the aftermath of that tragedy. Richard is a naturally skilled writer, and those abilities, along with a lifetime of trying to do an honest job as a reporter, eventually re-involve him in life.