By John Mort. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (March 8)

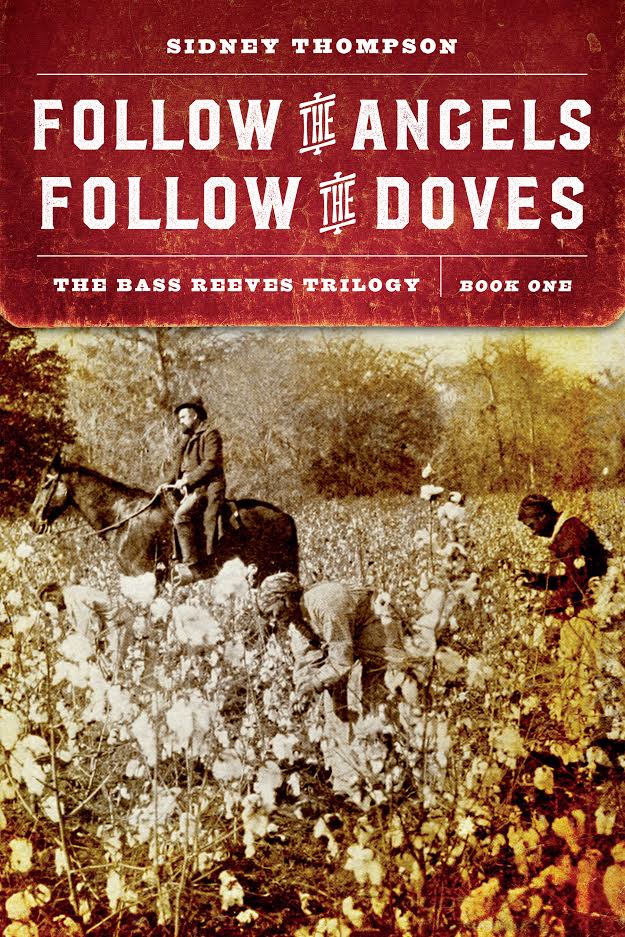

Bass Reeves—a real, historical figure—was born a slave on an Arkansas plantation in the 1840s. In Sidney Thompson’s new novel, Follow the Angels, Follow the Doves: The Bass Reeves Trilogy, Book One, Reeves grows up to be a big, agreeable man entirely loyal to his master, the redoubtable Master Reeves. Master Reeves is not cruel. When a black scullery maid has her baby, he gives her one day off, and this is regarded as kind by the scullery maid and everyone else.

Bass Reeves—a real, historical figure—was born a slave on an Arkansas plantation in the 1840s. In Sidney Thompson’s new novel, Follow the Angels, Follow the Doves: The Bass Reeves Trilogy, Book One, Reeves grows up to be a big, agreeable man entirely loyal to his master, the redoubtable Master Reeves. Master Reeves is not cruel. When a black scullery maid has her baby, he gives her one day off, and this is regarded as kind by the scullery maid and everyone else.

Slaves have so adapted to this patriarchal economic system that notions of emancipation and equality don’t occur to them. A kind of freedom exists just a few miles to the west, in Oklahoma Territory, but fleeing—running—is a tough concept. If you were beaten or starved, that would be one thing, but Master Reeves would never beat you or withhold food. You may be a slave, but you can live a life on Master Reeves’s plantation. You can marry. You can have kids.

It develops that Bass is an extraordinary marksman, and Master Reeves takes Bass to a number of turkey shoots in Arkansas and the Territory. Bass always wins, and the Master makes good money betting on him. Bass enjoys himself, and sometimes, he can bring those dead turkeys home for the other slaves.

Ignorance may have seemed like bliss, but Bass is a slave and a slave can be moved about like a horse. Old Master Reeves gives Bass to his son, young Master Reeves, who has a plantation down in Texas. Bass has a difficult time understanding this. He doesn’t know where Texas is, and doesn’t want to leave behind his aging parents. How could Master Reeves treat him like this?

The young Master Reeves is an intellectual with all sorts of theories about slavery. He baits Bass with his endless mind-games, trying to cause his new manservant to reveal his true feelings. In many ways, young Master Reeves inadvertently educates Bass and inculcates in him a desire for freedom. Young Reeves is despicable, but he’s also complicated. He fully understands how intelligent Bass is, and potentially how dangerous.

The Civil War has reached the West, and young Master Reeves wants a manservant who can shoot. Most of the Southern officers bring their manservants to the Battle of Wilson’s Creek (near Springfield, Missouri), a Southern victory of sorts that flows into the Southern defeat at Pea Ridge (near Fayetteville, Arkansas). These battles have been written about by historians and novelists alike, but Thompson’s treatment, portraying the war from a slave’s perspective, is unique.

The man-servant’s job is to reload weapons for their masters (for the most part, repeating rifles are not yet in use). But Bass is such an unerring shot that the young Master Reeves loads for his slave. And Bass kills many a Yankee, aiming for the brass buttons of their coats.

Young Master Reeves and Bass return to a changing Texas. The war isn’t over but everyone knows the South will lose. Throughout Bass’s faithful service, young Master Reeves has promised Bass’s manumission, or freedom; secretly, Bass, who has seen some of the world by now, has begun to contemplate running for his freedom into Oklahoma Territory. Just how to maneuver away from the devious young Master Reeves, and how to take leave of his sweetheart, Jennie, occupies the final pages of the first installment of this epic, three-volume portrait of Bass Reeves, the first black deputy west of the Mississippi.

When you’re gifted with the fine sense of characterization Thompson deploys, even the unsubtle subject of slavery grows subtler. His Young Master Reeves is a sort of Nazi, but he’s drawn masterfully. Thompson, once one of Barry Hannah’s students at University of Mississippi, is a highly entertaining writer, and his Bass Reeves emerges as an intelligent, reluctantly violent, sympathetic young man. Readers will find the compelling recreations of two important Civil War battles to be a kind of bonus.

John Mort is the author of Down Along the Piney: Ozarks Stories among others, and the winner of many awards for his fiction including a Spur Award from the Western Writers of America.

Sidney Thompson will be at Lemuria on Tuesday, March 10, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and discuss Follow the Angels, Follow the Doves.

Mildred Taylor wraps up her 10-book series that has followed the lives of the Logan family from slavery to the Civil rights movement with her final addition,

Mildred Taylor wraps up her 10-book series that has followed the lives of the Logan family from slavery to the Civil rights movement with her final addition,

Lara Prescott’s fictional account of three young women employed in the CIA’s typing pool who rise to the upper echelons of espionage during the 1950s Cold War is based on the true story of the agency’s undercover plan to smuggle copies of Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago into the USSR.

Lara Prescott’s fictional account of three young women employed in the CIA’s typing pool who rise to the upper echelons of espionage during the 1950s Cold War is based on the true story of the agency’s undercover plan to smuggle copies of Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago into the USSR.

Karl Marlantes says his penchant for writing long novels comes naturally: he has much to tell through his stories and the undercurrents he masterfully weaves just below the surface.

Karl Marlantes says his penchant for writing long novels comes naturally: he has much to tell through his stories and the undercurrents he masterfully weaves just below the surface.

So I absolutely have to tell you about another book that you are going to love:

So I absolutely have to tell you about another book that you are going to love:  I know that Charles Frazier is most known for his novel,

I know that Charles Frazier is most known for his novel,  Married at 17 to a man nearly 20 years her senior, Varina is thrust into political life during the brutality of the Civil War. She suffers the loss of several children and then decides to rescue a black child named Jimmie to raise as her own.

Married at 17 to a man nearly 20 years her senior, Varina is thrust into political life during the brutality of the Civil War. She suffers the loss of several children and then decides to rescue a black child named Jimmie to raise as her own.

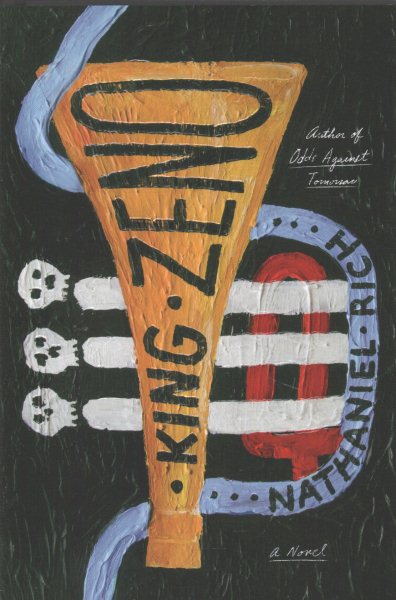

It’s a “crime” novel because it swirls around the notorious, real life crimes of an ax murder spree and wave of street robberies that struck 1918 New Orleans.

It’s a “crime” novel because it swirls around the notorious, real life crimes of an ax murder spree and wave of street robberies that struck 1918 New Orleans.