Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (June 2)

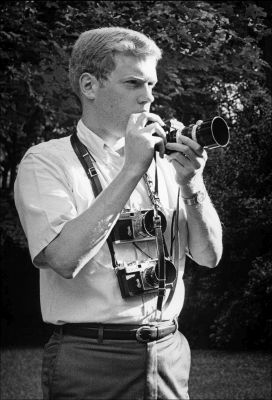

Pennsylvania native Michael Ford will tell you that his “snap decision” nearly 50 years ago–to ditch a dream job offer in Massachusetts, uproot his family, and move to Oxford, Miss. to pursue a hunch–turned out to be the best decision he ever made, as he launched his dreams that would ignite a successful and fulfilling career.

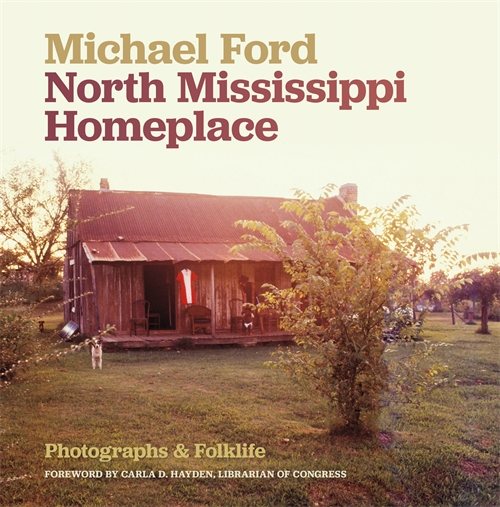

Now a filmmaker in Washington, D.C., Ford’s photo essays in his new book North Mississippi Homeplace: Photographs and Folklife (University of Georgia Press) reveal his passionate reverence for the area he has come to call his “homeplace.”

Now a filmmaker in Washington, D.C., Ford’s photo essays in his new book North Mississippi Homeplace: Photographs and Folklife (University of Georgia Press) reveal his passionate reverence for the area he has come to call his “homeplace.”

The unique volume contains only two chapters: one about moving to rural Mississippi and living in Oxford from 1972 to 1975; and the other explaining what brought him back multiple times four decades later. It includes scores of color photos taken during both periods. Ford notes that all these images–taken decades apart–invariably settled into three main themes: the land, the light and the people.

The materials he recorded for the documentary film he produced during his Mississippi stay are now archived in the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress as The Michael Ford Mississippi Collection.

During your first trip to visit in-laws in Oxford in December 1971, you made a quick decision to leave a secure teaching position at Boston’s Emerson College and move to Oxford with the idea of making a documentary film. Explain how this came about.

Michael Ford

I was working on my thesis film for my master’s program in film at Boston University. We had to design a master’s project and I had considered something about rural America, maybe in Vermont or New Hampshire.

When I began exploring the land (around the outskirts of Oxford) during that Christmas break, I had no reference for what I saw–the remoteness, the country shacks, the hogs’ legs hoisted in tree branches for gutting. I had studied (photography history) and I knew things like this shouldn’t exist in America anymore. I had done hard news for two years, and I knew there was a story here.

So, four months later, here I was, a Yankee, driving into Mississippi in an old VW bus with a peace sign on it and New York plates. I was just beginning to figure out that everyone might not like us so much. I began settling in with a deep immersion into the Mississippi hill country. I started reading Faulkner. I spent maybe six months driving and talking to people, getting a cold drink, and sometimes taking their pictures.

My number one anchor to the community was (Oxford blacksmith) Mr. (Morgan Randolph) Hall, who hired me as his apprentice. Number two was Hal Waldrip, who owned and ran an archaic general store in Chulahoma, Miss. He saw himself as one of the “keepers of the lore.” He told me, “I could fix this store up. I could add air conditioning and heat and clean it up. But it would lose some of the atmosphere.”

There were others–Doc Jones, who sold molasses at Waldrip’s store; AG Newson, who actually made the molasses with the help of his mules, Frank and Jake.

These were the people I found. They found me. They were important because they were all preserving this last flash of old times.

Tell me what you discovered about Mississippi–and yourself–as you began to capture the images in your book.

I had no idea this kind of life still existed in the U.S. anymore. I was making an independent documentary. You couldn’t make any preconceived ideas about where it was going. It designed itself. You can shape and interpret it, but you can’t invent it.

I realized that in a concrete sense when it came time to write it. It was the essence of the documentary–the experiences of the intuitive or spiritual side of life–that I wanted to share.

So, one of the things I had to learn as a documentarian was to shut up, that is, shut up the (analytical) left side of the brain, so the (creative) right side can do what it needs to do. I learned over the years that the best situation I could ask for was to shoot something and say, “I got it!” You just know. Words define a thing, but a photograph speaks for itself.

You write that your return visits to Mississippi in 2013-2015 were initially driven by nostalgia and curiosity. How did these trips of new discovery turn out?

What really sparked it were several things that came together at once. My grown daughter, who was a baby when we moved to Oxford, was insisting I do something with my film and audiotapes from Mississippi before I “croaked,” in her words; and technology had advanced to a point that I could do much of the work myself. That stuff had sat for 40 years in cans and boxes in my closets–not forgotten, but definitely ignored.

While reviewing old audio tapes, I listened to a recording of Mr. Hall talking to me. Out of nostalgia I Googled his name and (wound up getting) in touch with Andy Waller, an apprentice of Mr. Hall’s after I left Oxford. Andy had bought Mr. Hall out when he retired.

(That conversation) convinced me there was no doubt it was time to return . . . That was in April 2013. I’ve been back another half dozen times since then.

What I discovered was that it was different. The country people were gone, especially the older people. The sense of community had diminished. Today, even as far out as you can go in the country, you have can have a TV satellite and the internet. Having a place where people get together is difficult. There is not a downtown in most of these communities anymore.

The old way of life was mostly gone forever.

What did you ultimately learn from this whole unique experience, and how has it affected your life and career?

Two answers: one would be “everything.” It has affected everything. I lived where I’ve lived and done what I’ve done all because of it. I started my own film production company, Yellow Cat Productions, which I’ve had for 45 years. Maybe it taught me that I learned to take risks.

On our 1972 trip headed (from Massachusetts) to move to Mississippi, we stopped in New York and visited with (a friend). At that time, it felt in some ways like we were going to a land of darkness, chasing something I barely knew existed and wasn’t sure what to expect.

I told (my friend) that I wasn’t really sure why I should do this, and she said, “Why not?”

Everything changed at that instant. It was like I got it. I learned that when you look back, you see that it’s the single microseconds, not the big bangs, that change the course of a life.

I see the world in patterns, visually, and this is the way Mississippi works in my mind. Mississippi has a special place in this world.

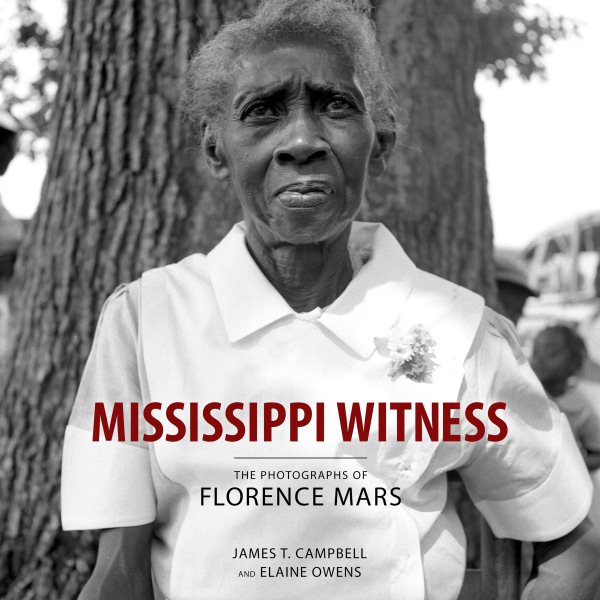

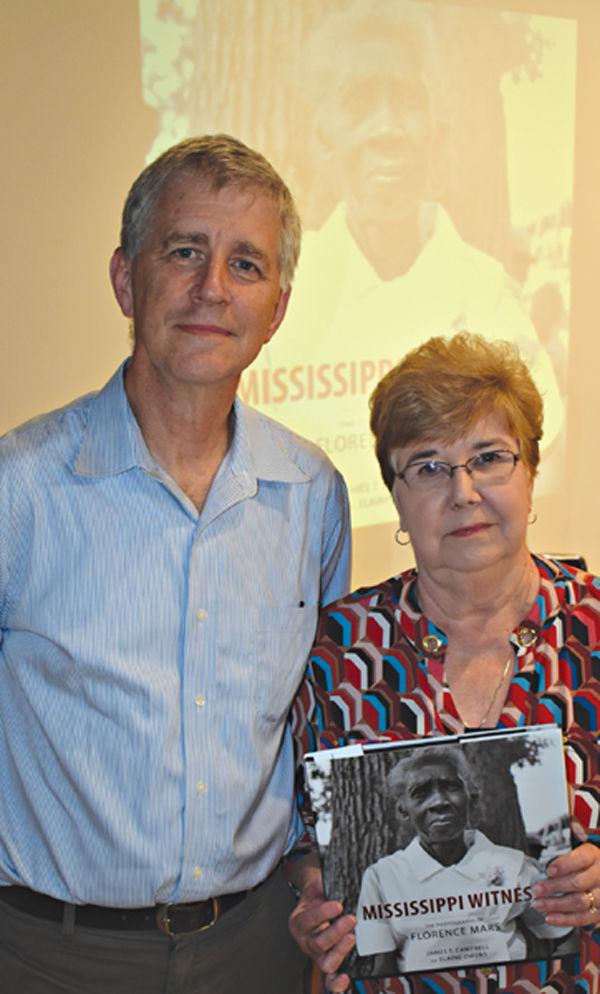

Mississippi Witness: The Photographs of Florence Mars

Mississippi Witness: The Photographs of Florence Mars

The Mistral is the wind that plagues Provence, as southern California is plagued by the Santa Ana winds. Over centuries of living in the region, the natives of Provence have learned ways to account for the strong and sudden wind.

The Mistral is the wind that plagues Provence, as southern California is plagued by the Santa Ana winds. Over centuries of living in the region, the natives of Provence have learned ways to account for the strong and sudden wind. In fact, Isbell’s monumental work is a response to Katrina and the resiliency of our coastal institutions and residents. As a Pulitzer-Prize winning photographer, he chronicled the destruction of the hurricane for The Sun Herald, the Gulfport/Biloxi-based daily newspaper. Isbell explains in his introduction to the The Mississippi Gulf Coast that the work has “special meaning, as it was a therapeutic endeavor after the destruction from Hurricane Katrina.”

In fact, Isbell’s monumental work is a response to Katrina and the resiliency of our coastal institutions and residents. As a Pulitzer-Prize winning photographer, he chronicled the destruction of the hurricane for The Sun Herald, the Gulfport/Biloxi-based daily newspaper. Isbell explains in his introduction to the The Mississippi Gulf Coast that the work has “special meaning, as it was a therapeutic endeavor after the destruction from Hurricane Katrina.”

In her new book,

In her new book,

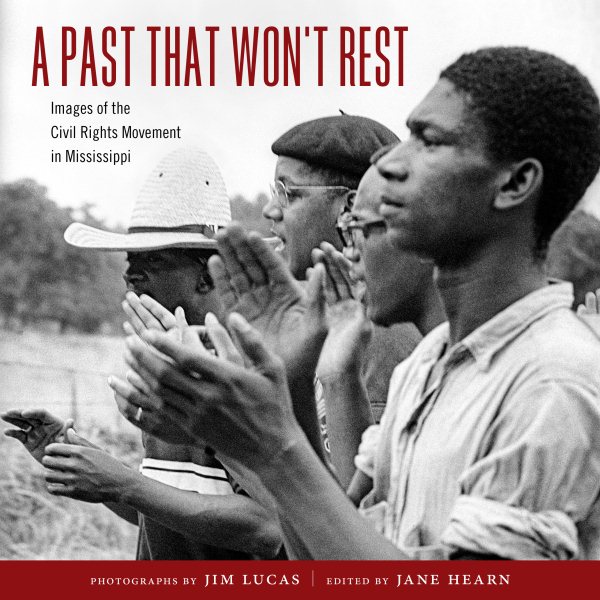

The University Press of Mississippi publication features more than 100 never-before-seen photographs taken by Lucas from 1964 to 1968 that focus on four Mississippi historic events, with a fifth chapter putting recent national episodes of activist violence into historical perspective. These chapters are bolstered with narratives contributed by Dr. Howard Ball, Peter Edelman, Aram Goudsouzian, Robert E. Luckett Jr., Ellen B. Meacham, and Stanley Nelson, with a foreword by Charles L. Overby.

The University Press of Mississippi publication features more than 100 never-before-seen photographs taken by Lucas from 1964 to 1968 that focus on four Mississippi historic events, with a fifth chapter putting recent national episodes of activist violence into historical perspective. These chapters are bolstered with narratives contributed by Dr. Howard Ball, Peter Edelman, Aram Goudsouzian, Robert E. Luckett Jr., Ellen B. Meacham, and Stanley Nelson, with a foreword by Charles L. Overby.