Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (November 4)

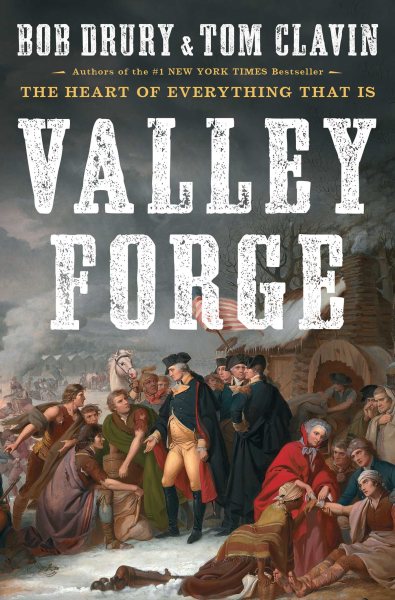

By examining the true story of George Washington’s six-month battle with disease, desertion, and frigid weather as he turned the Continental Army into a fighting force that would win America’s freedom from the British, co-authors Bob Drury and Tom Clavin show readers how this turning point in U.S. history is still relevant today.

Valley Forge is the pair’s sixth book together, supported by research that includes thousands of original documents written or dictated by Washington and highlighted with “a cast of iconic characters”–some of whose names have faded from history but who were instrumental in America’s struggle for freedom.

Valley Forge is the pair’s sixth book together, supported by research that includes thousands of original documents written or dictated by Washington and highlighted with “a cast of iconic characters”–some of whose names have faded from history but who were instrumental in America’s struggle for freedom.

Drury and Clavin’s previous books include the New York Times number one bestseller The Heart of Everything That Was, and other New York Times bestsellers Halsey’s Typhoon, Last Men Out, and The Last Stand of Fox Company.

Drury said his collaboration with Clavin has “settled into a process” of shared research, with him conducting interviews and Clavin taking the lead in editing.

“He is a very good editor, and I do the writing,” Drury said. “We realized we couldn’t have four hands on the keyboard.”

Bob Drury

All told, Drury has authored and/or edited nine books, and his work has also appeared in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, Men’s Journal and GQ. Nominated for three National Magazine Awards and a Pulitzer Prize, Drury has covered news in Iraq, Afghanistan, Liberia, Bosnia, Northern Ireland, and Darfur, among other sites. He makes his home at the Jersey shore.

Clavin, who lives in Sag Harbor, New York, has worked as a reporter for the New York Times, and has served as a newspaper and web site editor, as well as working as a magazine writer and TV and radio commentator. He has earned awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the National Newspaper Association.

What was it about Washington that motivated him to persevere despite not only the conditions of the Valley Forge winter, but the political battles he also fought on a regular basis?

In public, Washington showed his steely will, but we discovered a different side. In private, he was very conflicted. One of the tensions of Valley Forge was that Washington had the weight of the war and the protection of his men on his shoulders, as well as his political relationship with the Continental Congress–and it burdened him.

He had the console of his young officers and “surrogate sons”–the Marquis de Lafayette, who was only 19; Alexander Hamilton, who was 22; and John Laurens – the “forgotten founding father,” also 22. Alone, he unburdened himself to (his wife) Martha.

I have personally read every (document) Washington wrote during (a period from) 1777 to 1778. He wrote about how he felt the burden he could never show to the Congress. On the outside he kept a steely composure and will. His confidants and his journals allowed him to keep his composure.

Of the 2,000 men who perished at Valley Forge (that winter of 1777-1778), half died of starvation and exposure, and half from diseases like typhus, typhoid and cholera.

Washington had to make an example of himself. He was driven. We don’t think of Washington as insecure. But earlier he had to take orders from British officers whom he outranked. He was a man who had no college education. Yet he became the father of our country

Through the years, several other authors have written books about the events at Valley Forge that winter. What is it about your account of Valley Forge that separates it from other books?

We contend that Valley Forge was THE turning point of the American Revolution. As we were putting this book together, we knew that other (authors) have disagreed. Everyone has their own feeling of what was the turning point for the Americans. We give a view of Washington they’ve never seen before. We decided early on that we would be prepared for this (challenge).

We present a cast of characters others have not, and we dispel many of the myths.

One of those myths is the notion of what bad luck it was for George Washington and his men to have been at Valley Forge in such a bad winter. Actually, it was one of the mildest on record at that time. The records show that it would snow, then soon turn 40 degrees, then it would rain, and everything would turn to mud–and the latrines would overflow. Over 500 horses starved to death in the freezing cold. They would be buried about a foot deep, and the heavy rains would wash their bodies up. Together, this created a pervasive odor that hung over the camp and made it miserable.

Another myth was that everyone (around the Valley Forge area) was starving to death, but 1777 produced the greatest harvest of the decade. There was plenty of corn, wheat, cattle, and mutton. The problem for the soldiers was that the local farmers preferred to smuggle their foods to the British Army for money. Remember, not all Americans supported the revolution. About 40 percent of the country’s population then were for the revolution; about 20 percent remained loyalists to King George, and the other 40 percent were really not committed to either side.

Another fact we bring to light is that this was the first time in American history that the military was integrated. There were 750 black soldiers, all free men from the northeast, who fought alongside the Continental Army. American military units were not integrated again until the Korean War (in the 1950s).

If the British had chosen to attack Washington and his men at Valley Forge that winter, history would have surely been changed forever. Do you think it was America’s destiny that it didn’t turn out that way?

I think it was a combination of destiny and British hubris. Back then there was a “fighting season” in temperate climates, and armies didn’t fight in winter. If they had attacked Washington at Valley Forge that winter, they would have overrun the American forces in a minute. They were overconfident that they would brush the Continental Army like a piece of lint off their shoulder. They thought that in the spring, they would take care of this rag-tag army.

I think it was a little destiny, a little luck, and a lot of British hubris.

When you’re researching a book that dates back this far, do you find yourself in awe of the fact that you’re looking at actual diaries and documents that are as old as these, and that they belonged to real people?

Oh, yes. Valley Forge is so well documented. I read nearly 2,000 documents that were written or dictated by Washington. Quite often with centuries-old documents like diaries or journals, university libraries and sometimes historical societies preserve them in such a way that you cannot touch them with your hands. They may be stored in fiberglass boxes and you have to turn the pages with tongs because they’re so old and fragile.

On one hand it makes you realize how young this country is. Also, we can clearly see what we think we know about Washington, and what is actually true. His writings show us his angst and self-doubt about things we never think of.

Why do we need to be reminded about Valley Forge today–and how can we apply the hard-fought lessons of what they endured and what their sacrifice helped make possible?

Not to be too political, but our country is so polarized today–not that it wasn’t in 1777 and 1778. At that time the U.S. was in an age of enlightenment: there was a novel idea that thinking itself, and definitely expressing those thoughts, that was the ultimate form of political engagement.

I think that’s something we’ve lost today, and that (finding it again) would move our country forward.

Bob Drury will at Lemuria on Monday, November 12, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and read from Valley Forge. Valley Forge is Lemuria’s November 2018 selection for its First Editions Club for Nonfiction.

Well, the season is upon us: hundreds of hungry children dressing up like princesses and superheroes, anticipating candy by the truckload. But my treat came early in the form of John M. Floyd’s seventh exciting collection of mystery short stories.

Well, the season is upon us: hundreds of hungry children dressing up like princesses and superheroes, anticipating candy by the truckload. But my treat came early in the form of John M. Floyd’s seventh exciting collection of mystery short stories.  For the characters of Beth Kander’s

For the characters of Beth Kander’s  Cobb’s new book,

Cobb’s new book,

How the couple has gotten to this point is the result of two lifetimes of struggles and triumphs as documented in their memoir,

How the couple has gotten to this point is the result of two lifetimes of struggles and triumphs as documented in their memoir,

Although, effortless is a bit misleading. In interviews, conversations, and in the very content of the book, Laymon admits that Heavy was difficult to write. It was necessary. This duality persists throughout the layers of the memoir. The relationship Laymon describes with his mother is at times toxic, but is also nurturing, sincere, and life-giving. The relationship Laymon has with his own body and food moves between destructive and healthy. Growing up as a brilliant black child in Mississippi is both “burden and blessing,” to borrow Laymon’s own words. In the face of one-dimensional, monolithic, unimaginative stereotypes, Laymon spits nuance and grace and honesty—honesty that is gritty and soothing, that captures the “contrary states of the human soul,” as William Blake says.

Although, effortless is a bit misleading. In interviews, conversations, and in the very content of the book, Laymon admits that Heavy was difficult to write. It was necessary. This duality persists throughout the layers of the memoir. The relationship Laymon describes with his mother is at times toxic, but is also nurturing, sincere, and life-giving. The relationship Laymon has with his own body and food moves between destructive and healthy. Growing up as a brilliant black child in Mississippi is both “burden and blessing,” to borrow Laymon’s own words. In the face of one-dimensional, monolithic, unimaginative stereotypes, Laymon spits nuance and grace and honesty—honesty that is gritty and soothing, that captures the “contrary states of the human soul,” as William Blake says. While this “modern day reinterpretation” of the classic book has retained many favorite recipes from the original, it is filled with popular choices from recent editions of Southern Living magazine, and many of Heiskell’s own favorites. Menus include appetizers, main dishes, drinks, and desserts for a Bridal Tea, Garden Club Luncheon, Summer Nights, Cocktails and Canapés, Tailgate, Picnic on the Lawn, Fall Dinner, and 24 more occasions.

While this “modern day reinterpretation” of the classic book has retained many favorite recipes from the original, it is filled with popular choices from recent editions of Southern Living magazine, and many of Heiskell’s own favorites. Menus include appetizers, main dishes, drinks, and desserts for a Bridal Tea, Garden Club Luncheon, Summer Nights, Cocktails and Canapés, Tailgate, Picnic on the Lawn, Fall Dinner, and 24 more occasions.

It’s a fascinating voyage into the Golden Age of Piracy that not only proves true some of the stereotypes of legend, book and film, but also debunks others and shockingly reveals the depth of early America’s connection to the outlaw seafarers.

It’s a fascinating voyage into the Golden Age of Piracy that not only proves true some of the stereotypes of legend, book and film, but also debunks others and shockingly reveals the depth of early America’s connection to the outlaw seafarers. Though lesser known than other heroic military campaigns throughout America’s history, the struggle that played out along the frozen shores of the Chosin Reservoir in the snowy mountains of North Korea in 1950 tested the mettle of the First Marine Division beyond reason.

Though lesser known than other heroic military campaigns throughout America’s history, the struggle that played out along the frozen shores of the Chosin Reservoir in the snowy mountains of North Korea in 1950 tested the mettle of the First Marine Division beyond reason.