Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (December 1)

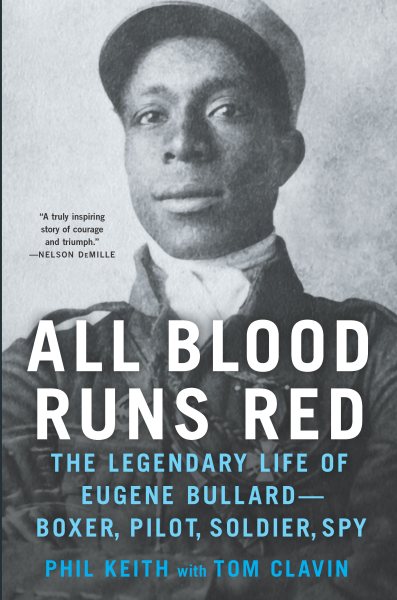

Author Phil Keith adds his sixth book to his collection as his collaboration with bestselling writer Tom Clavin unfolds the almost unbelievable story of bravery and valor of a little-known World War I hero in All Blood Runs Red: The Legendary Life of Eugene Bullard–Boxer, Pilot, Soldier, Spy.

Author Phil Keith adds his sixth book to his collection as his collaboration with bestselling writer Tom Clavin unfolds the almost unbelievable story of bravery and valor of a little-known World War I hero in All Blood Runs Red: The Legendary Life of Eugene Bullard–Boxer, Pilot, Soldier, Spy.

Bullard was the first African American military pilot who flew in combat, and the only one to serve as a pilot in World War I. He would later become a jazz musician, a night club owner in Paris, and a spy during the French Resistance.

Among Keith’s previous volumes is Blackhorse Riders, winner of the 2012 award from USA Book News for Best Military Non-Fiction. He was also a finalist for the 2013 Colby Award, and earned a silver medal from the Military Writers Society of America that same year.

He holds a degree in history from Harvard University, and is a former Navy aviator. During three tours in Vietnam, he was awarded the Purple Heart, Air Medal, Presidential Unit Citation, and the Navy Commendation Medal, among other honors.

Your book states that Eugene Bullard led a “legendary life” as a boxer, pilot, highly decorated soldier, and a spy. Why has his story been so little known?

Phil Keith

Three reasons, primarily: Gene fought for France in World War I, and, of course, he was black. Not many in America, during World War I, were interested in hearing stories about courageous African Americans. The times were still too racially charged, and even the American Air Service had an official policy that banned blacks from serving.

Secondly, all during his World War I experiences, he was constantly badgered and put down by a particularly racist American living in Paris, Dr. Edmund Gros. This doctor was the founder of the famed American Ambulance Service and co-founder of what became the Lafayette Flying Corps. He was a virulent hater of blacks, and of Gene in particular, because Bullard had been so successful despite Gros’ best efforts to ground him. Gros constantly omitted his name from recognition of Americans helping in the war effort and eventually was successful in getting Gene bounced out of French aviation.

Thirdly, when Gene returned to America, he wrote his autobiography in the late 1950s. That was at a time when Franco-American relations were at a low ebb; and, the editors who reviewed his manuscript thought it was too fantastical to be true, especially for a barely educated black man.

How did you hear about Bullard, and how did you handle the research for this book, working with information that was not only hard to find, but often conflicting?

Doing research for a book on World War I, with a chapter on America’s famous aviators, I came across a footnote in some Eddie Rickenbacker material that mentioned Bullard. That was the first I had ever heard of him. I was fascinated and began to dig.

I found the only existing archive on Bullard at Columbus State University in his hometown of Columbus, Ga. I spent a week combing through their boxes. We also found bits and pieces of the Bullard story in other bios, particularly his famous contemporaries.

And, yes, there were conflicting stories, so we had to set up a rigorous process of “triangulation:” Nothing got in the book unless it could be confirmed by at least two other sources.

Despite the obstacles, why did you and your co-author Tom Clavin believe Bullard’s story needed to be told?

Bullard is clearly one of the most fascinating historical figures of the 20th century yet very few people know about him; so, from that standpoint alone, his story is important–fills in a missing piece. Perhaps even more importantly, Bullard’s story should be a role model for today’s African American young men and women. He is a true hero who can be looked up to and his examples of determination and persistence are crucial, we think, to the telling of the experiences of post-slavery blacks in America and Europe.

How did you two split up the writing of this book?

Tom is a dogged researcher, so he got the task of “story-hound,” except for the sojourn to Georgia. Much of the original sleuthing went to Tom. We also wrote to our individual strengths: I concentrated on the military aspects of Gene’s life, for example, and Tom, who has written several sports books, did the work on Gene’s boxing days. I did most of the rough draft manuscript, and Tom did the vast majority of the editing and smoothing. I had never done a collaboration before, but Tom has. I have to say it went very smoothly. It was so smooth, in fact, that our editor at Hanover Square Press immediately optioned our next book idea, which is in progress now. It will be a ripping good sea story about the Civil War’s most famous sea battle between the USS Kearsarge and the CSS Alabama.

Please share the story of how the title of this book was chosen.

“All Blood Runs Red” is the Anglicized version of the French “Tous Sange Que Coule C’est Rouge.” This was the motto Bullard had stenciled on the sides of his SPAD fighter plane, with the words surrounding a large red heart with a dagger stuck in it. For Bullard, he wanted to make the point that “we’re all in this (the war) together.” It did not matter the color of any man’s skin: when any soldier bled, all the blood was red. This was also the title of his never published autobiography (1960) and we wanted to use it in his honor.

Phil Keith will at Lemuria on Tuesday, December 3, at 5:00 p.m. to sign copies of and discuss All Blood Runs Red. Lemuria has selected All Blood Runs Red its December 2019 selection for its First Editions Club for Nonfiction.

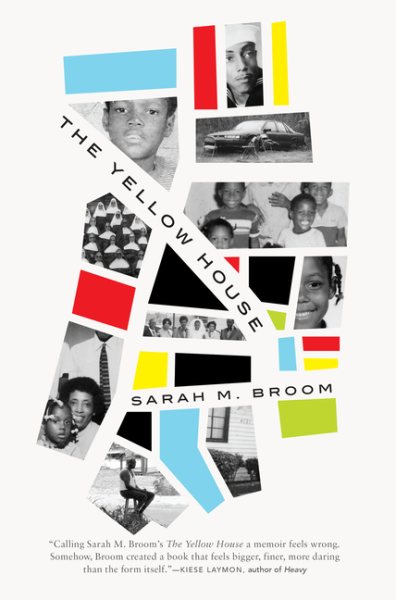

Childhood homes are harbors of our rearing, keepers of our secrets and reflections of our parents. It’s our first understanding of what “home” actually means, and the way it always pulls us back.

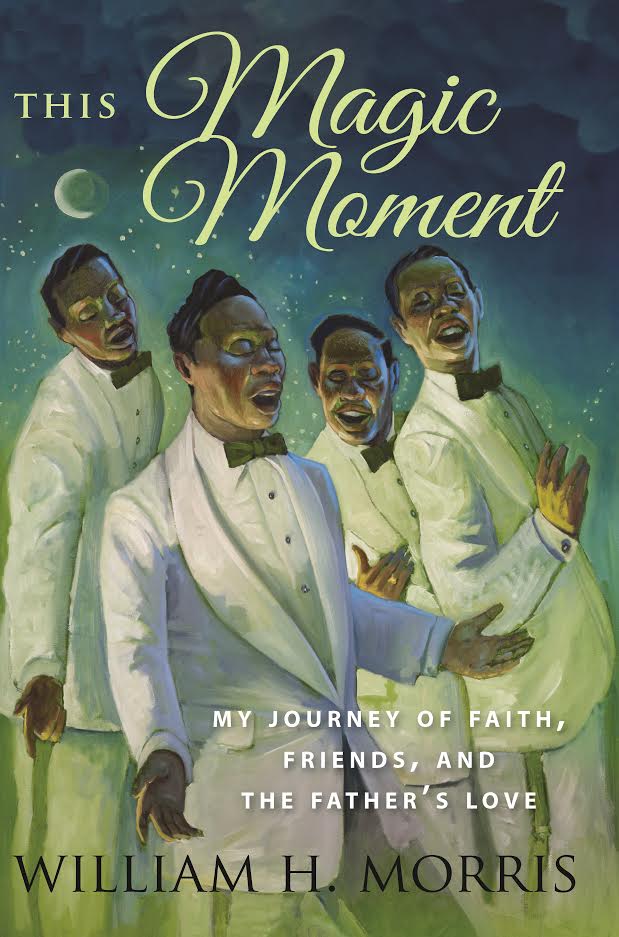

Childhood homes are harbors of our rearing, keepers of our secrets and reflections of our parents. It’s our first understanding of what “home” actually means, and the way it always pulls us back. William H. (Bill) Morris would tell you that he has had more than his share of “magic moments’ in his lifetime, and he shares many details of his close-knit friendships with some of the greatest musicians of the R & B, Rock and Roll and Doo-Wop era of the ‘50s and ‘60s in his heartfelt memoir,

William H. (Bill) Morris would tell you that he has had more than his share of “magic moments’ in his lifetime, and he shares many details of his close-knit friendships with some of the greatest musicians of the R & B, Rock and Roll and Doo-Wop era of the ‘50s and ‘60s in his heartfelt memoir,

Since so much of John Hodgman’s new memoir,

Since so much of John Hodgman’s new memoir,  It is the global projection of this image, as imperfect as it may be in actuality, that has long been a part of the lore and lure of the United States of America. It is the mirage that entices thousands upon thousands of people to leave their troubled homelands and, sometimes, risk their lives to come to “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” where they are free to live their lives as they see fit, worship the God of their choice, and consume as much as their wallet will allow.

It is the global projection of this image, as imperfect as it may be in actuality, that has long been a part of the lore and lure of the United States of America. It is the mirage that entices thousands upon thousands of people to leave their troubled homelands and, sometimes, risk their lives to come to “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” where they are free to live their lives as they see fit, worship the God of their choice, and consume as much as their wallet will allow. Hailman’s fifth book gives us a world filled with adventures, romances, and intrigue he experienced during a lifetime of international travels, beginning as a university student living in France. Traveling the world later as a representative for the U.S. Justice Department, Hailman encountered criminals and conspiracies, including a plot in Ossetia, Georgia, to hijack his helicopter and kidnap him. He brings these adventures to life in this engaging and exciting book.

Hailman’s fifth book gives us a world filled with adventures, romances, and intrigue he experienced during a lifetime of international travels, beginning as a university student living in France. Traveling the world later as a representative for the U.S. Justice Department, Hailman encountered criminals and conspiracies, including a plot in Ossetia, Georgia, to hijack his helicopter and kidnap him. He brings these adventures to life in this engaging and exciting book.

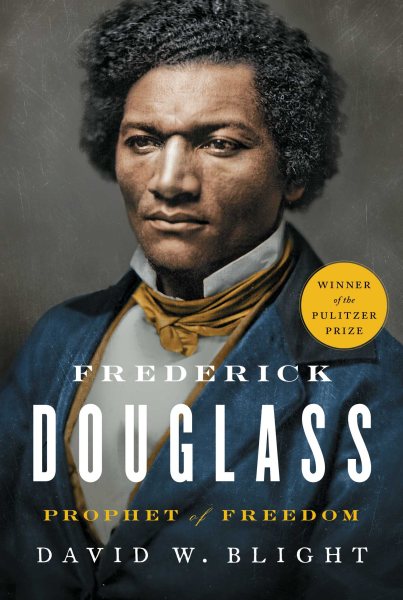

Blight’s biography, which won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in History, offers a similar intensity, but pulls the camera back to offer a wider-angle view. We are greeted with the larger political and social contexts through which Douglass’ life flowed, yet Blight’s writing never looses its focus on Douglass’ own experiences. Showing these intersections between national history and Douglass’ personal history allows Blight to muse on how Douglass’ writing and activism affected the American abolitionist movements, and how the various gears of those movements affected Douglass personally.

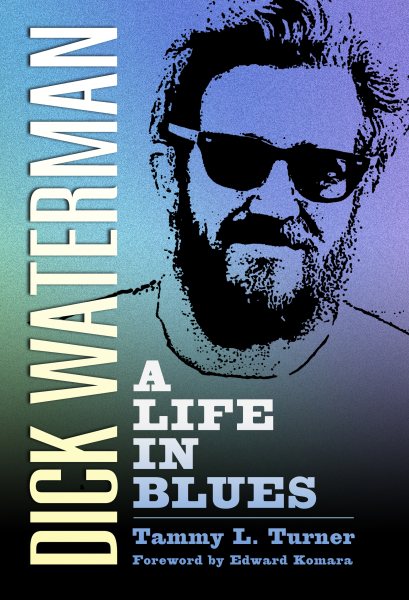

Blight’s biography, which won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in History, offers a similar intensity, but pulls the camera back to offer a wider-angle view. We are greeted with the larger political and social contexts through which Douglass’ life flowed, yet Blight’s writing never looses its focus on Douglass’ own experiences. Showing these intersections between national history and Douglass’ personal history allows Blight to muse on how Douglass’ writing and activism affected the American abolitionist movements, and how the various gears of those movements affected Douglass personally. A member of the Blues Hall of Fame, Waterman managed, booked, and/or photographed essentially the entire Delta Blues revival as well as the electric blues apex of the 60s. Who else could write B.B. King’s biography, introduce unreleased Robert Johnson tracks to Eric Clapton, or receive an apology from Bill Graham? Guided by his level head and committed heart, Dick made many allies and musical history.

A member of the Blues Hall of Fame, Waterman managed, booked, and/or photographed essentially the entire Delta Blues revival as well as the electric blues apex of the 60s. Who else could write B.B. King’s biography, introduce unreleased Robert Johnson tracks to Eric Clapton, or receive an apology from Bill Graham? Guided by his level head and committed heart, Dick made many allies and musical history.