“Afoot and light hearted, I take to the open road.” So begins Whitman’s long poem “Song of the Open Road,” a delightful, meandering meditation on what it means to be human. A theme that Whitman hammers into this poem, without a hint of subtlety, is the familiar “the journey is the destination,” a trope that has had countless iterations over time. Frank LaRue Owen’s new book, The Temple of Warm Harmony, follows in the same vein as Whitman, Homer, and Kerouac, yet he finds inspiration in the Eastern traditions of Zen and Pure Land Buddhism. It’s hard to classify which genre to place Temple: it could be shelved with poetry or with metaphysical studies or Zen meditation. But tacking The Temple of Warm Harmony down into a tidy category is antithetical to the book’s very purpose. Rather than telling us to be something, Owen’s poems invite us to simply be, whatever and wherever we are.

“Afoot and light hearted, I take to the open road.” So begins Whitman’s long poem “Song of the Open Road,” a delightful, meandering meditation on what it means to be human. A theme that Whitman hammers into this poem, without a hint of subtlety, is the familiar “the journey is the destination,” a trope that has had countless iterations over time. Frank LaRue Owen’s new book, The Temple of Warm Harmony, follows in the same vein as Whitman, Homer, and Kerouac, yet he finds inspiration in the Eastern traditions of Zen and Pure Land Buddhism. It’s hard to classify which genre to place Temple: it could be shelved with poetry or with metaphysical studies or Zen meditation. But tacking The Temple of Warm Harmony down into a tidy category is antithetical to the book’s very purpose. Rather than telling us to be something, Owen’s poems invite us to simply be, whatever and wherever we are.

The book is arranged like a classical comedy. Poems at the beginning of the book show the speaker’s struggle with strife, loneliness, and feeling spiritually lost, having lost the tao, or the path, upon which he wishes to tread. In the end, though, we gain hope. “Sometimes the inner and outer/ move along like birds/ gliding in different directions,” Owen tells us in “Teaching of the Seasons.” Even though these “birds” of body and soul are moving in opposite directions, there is a peace to this split. They are “gliding,” unobstructed, to their various ends. Sometimes—often —the physical and spiritual are at opposing ends to each other, yet Owen doesn’t require that our currents be parallel for us to find contentment.

There are times when a reader’s defensiveness might make one look at Owen’s high-minded contentment as arrogance, but nothing could be farther from the truth. “Who is this guy, and why does he claim to have it all figured out,” one might ask. Well, he doesn’t know it all, and this is the source of the book’s wisdom. Part metaphysical self-help guide, part image-driven poetry, part Zen meditative koan collection, The Temple of Warm Harmony offers quiet in a time we desperately need it. When the barrage of news and tweets and noise (literal and otherwise) send us into an overwhelmed, bloated fatigue, Frank LaRue Owen offers us simplicity.

Frank LaRue Owen will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, November 20, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and discuss The Temple of Warm Harmony. He will also be at Lemuria on Saturday, December 21, at 2:00 p.m. in a joint event with Beth Kander, author of Born in Syn.

First, a little in-universe context. Dog Man is a book-within-a-book series, “written” by George and Harold, the mischievous heroes of Pilkey’s zany Captain Underpants series. Dog Man was the duo’s first foray into comic making, and we’re better people for it. The titular character has, like all super heroes, an interesting origin story: the city’s best cop and best police dog are injured in an explosion. The dog’s body is badly injured, but his head is intact; his human partner’s injuries are the exact opposite. A nurse suggests a reasonable way to save both—sew the dog’s head on the man’s body. Thus, Dog Man, crime fighter extraordinaire.

First, a little in-universe context. Dog Man is a book-within-a-book series, “written” by George and Harold, the mischievous heroes of Pilkey’s zany Captain Underpants series. Dog Man was the duo’s first foray into comic making, and we’re better people for it. The titular character has, like all super heroes, an interesting origin story: the city’s best cop and best police dog are injured in an explosion. The dog’s body is badly injured, but his head is intact; his human partner’s injuries are the exact opposite. A nurse suggests a reasonable way to save both—sew the dog’s head on the man’s body. Thus, Dog Man, crime fighter extraordinaire.

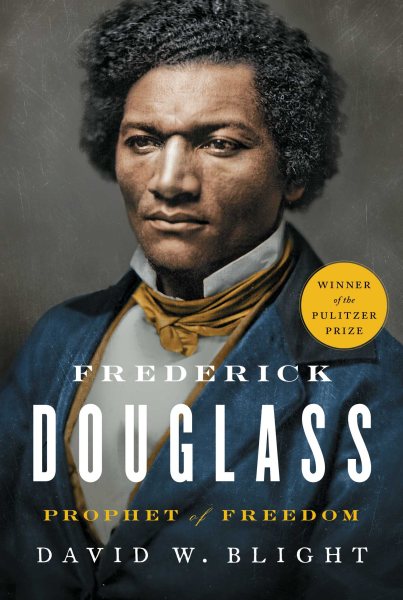

Blight’s biography, which won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in History, offers a similar intensity, but pulls the camera back to offer a wider-angle view. We are greeted with the larger political and social contexts through which Douglass’ life flowed, yet Blight’s writing never looses its focus on Douglass’ own experiences. Showing these intersections between national history and Douglass’ personal history allows Blight to muse on how Douglass’ writing and activism affected the American abolitionist movements, and how the various gears of those movements affected Douglass personally.

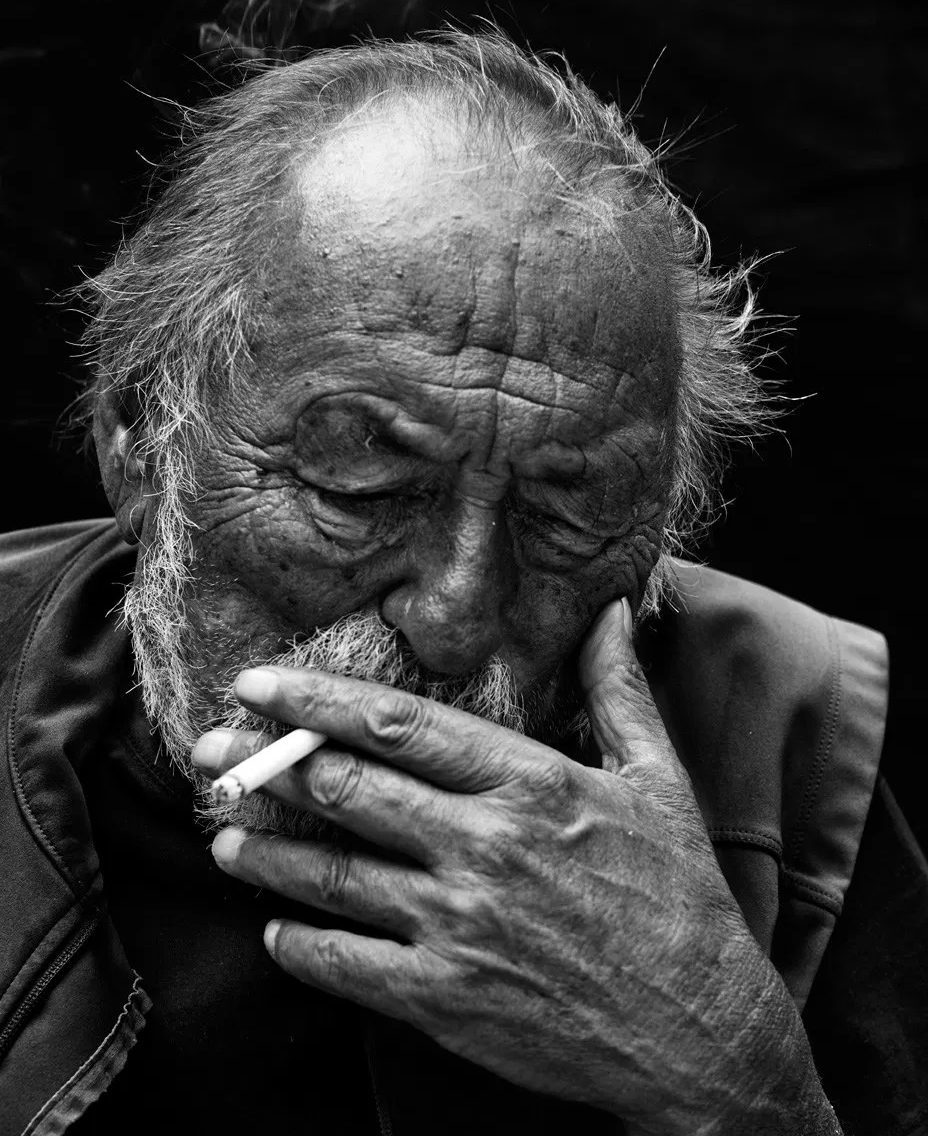

Blight’s biography, which won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in History, offers a similar intensity, but pulls the camera back to offer a wider-angle view. We are greeted with the larger political and social contexts through which Douglass’ life flowed, yet Blight’s writing never looses its focus on Douglass’ own experiences. Showing these intersections between national history and Douglass’ personal history allows Blight to muse on how Douglass’ writing and activism affected the American abolitionist movements, and how the various gears of those movements affected Douglass personally. Jim Harrison knew he was dying when he wrote the poems in Dead Man’s Float. The grace with which he accepts his very end is comforting, but not all of the poems are about his life’s sunset. In another imitating-animals move, the poem “Mad Dog,” Harrison tells us that he “envied the dog lying in the yard,” so he lies down with it, rolling around, unable to find the same level of blissful comfort that his canine counterpart does. We’ve all been here: trying to make ourselves happy but blocked by ourselves. It’s funny, tongue in cheek, light.

Jim Harrison knew he was dying when he wrote the poems in Dead Man’s Float. The grace with which he accepts his very end is comforting, but not all of the poems are about his life’s sunset. In another imitating-animals move, the poem “Mad Dog,” Harrison tells us that he “envied the dog lying in the yard,” so he lies down with it, rolling around, unable to find the same level of blissful comfort that his canine counterpart does. We’ve all been here: trying to make ourselves happy but blocked by ourselves. It’s funny, tongue in cheek, light. Although, effortless is a bit misleading. In interviews, conversations, and in the very content of the book, Laymon admits that Heavy was difficult to write. It was necessary. This duality persists throughout the layers of the memoir. The relationship Laymon describes with his mother is at times toxic, but is also nurturing, sincere, and life-giving. The relationship Laymon has with his own body and food moves between destructive and healthy. Growing up as a brilliant black child in Mississippi is both “burden and blessing,” to borrow Laymon’s own words. In the face of one-dimensional, monolithic, unimaginative stereotypes, Laymon spits nuance and grace and honesty—honesty that is gritty and soothing, that captures the “contrary states of the human soul,” as William Blake says.

Although, effortless is a bit misleading. In interviews, conversations, and in the very content of the book, Laymon admits that Heavy was difficult to write. It was necessary. This duality persists throughout the layers of the memoir. The relationship Laymon describes with his mother is at times toxic, but is also nurturing, sincere, and life-giving. The relationship Laymon has with his own body and food moves between destructive and healthy. Growing up as a brilliant black child in Mississippi is both “burden and blessing,” to borrow Laymon’s own words. In the face of one-dimensional, monolithic, unimaginative stereotypes, Laymon spits nuance and grace and honesty—honesty that is gritty and soothing, that captures the “contrary states of the human soul,” as William Blake says. Hosseini’s newest book,

Hosseini’s newest book,  Michael Chabon’s

Michael Chabon’s  Jesmyn Ward’s

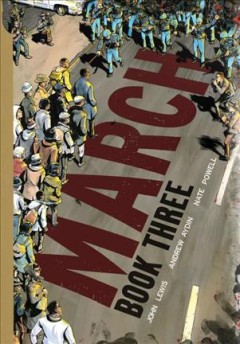

Jesmyn Ward’s  With the occasional jump back into the narrative present, March follows Lewis’ life using major civil rights events (the

With the occasional jump back into the narrative present, March follows Lewis’ life using major civil rights events (the  It’s also compellingly told. Lewis’ tone is conversational: it balances seriousness and grief with levity and honesty. Anyone who’s heard Senator Lewis speak knows he does so with conviction but without false airs, and March is written the same way.

It’s also compellingly told. Lewis’ tone is conversational: it balances seriousness and grief with levity and honesty. Anyone who’s heard Senator Lewis speak knows he does so with conviction but without false airs, and March is written the same way.

Like all of Rash’s fiction, The Risen is set in North Carolina, and this place informs both the characters and plot. Our narrator, Eugene, tells us two parallel stories: first, he recalls his youth, specifically the

Like all of Rash’s fiction, The Risen is set in North Carolina, and this place informs both the characters and plot. Our narrator, Eugene, tells us two parallel stories: first, he recalls his youth, specifically the