by Andrew Hedglin

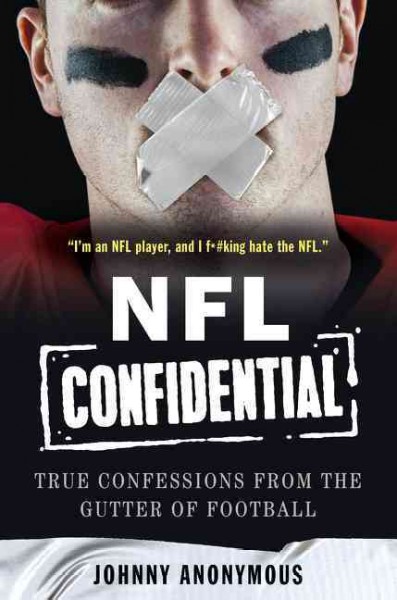

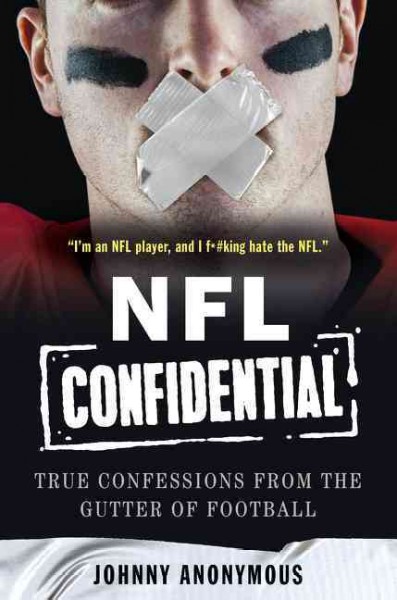

Johnny Anonymous, a white offensive lineman in the NFL who wishes to remain, well…anonymous, opens his book NFL Confidential with a pretty audacious challenge: “…I changed a bunch of…names, timeline, details, the usual. All so you can’t figure out who I really am. Go ahead, try. I dare you. Catch me if you can.”

Johnny Anonymous, a white offensive lineman in the NFL who wishes to remain, well…anonymous, opens his book NFL Confidential with a pretty audacious challenge: “…I changed a bunch of…names, timeline, details, the usual. All so you can’t figure out who I really am. Go ahead, try. I dare you. Catch me if you can.”

That’s a short order in the internet age, especially for somebody who plays in the NFL and is so awash in publicly available information, regardless of how unimportant he thinks he is. I won’t link to the page that floats a very convincing theory as to the author’s real identity, but you can find it with a cursory Google search. As I read the book with this person’s identity in mind, it became clear: all the puzzle pieces fit.

But why all the cloak-and-dagger in the first place? What secrets about the NFL is he going to blow open for the reader? Is it any worse than what we already know–concussions, performance-enhancing drugs , franchises extorting money from cities for new stadiums, and domestic violence?

I mean, not really. If there is one thing he focuses on that will probably leave the reader feeling most uneasy, it’s the excruciating toll being a pro football player takes on the bodies and minds of the people who play the sport, both in the short-term of maintaining weight (things get fairly scatalogical) and the dark spectre of long-term damage.

The other thing he seems to hate about the NFL is the insecurity. Certainly, this is ultimately exemplified in job insecurity, especially for players on the margins like him, who are always in danger of getting cut. Even though “scrubs” make hundreds of thousands of dollars per year, that doesn’t always go as far you’d think. Because he only has one year left on his contract, he can’t even get a mortgage for a modest home he tries to buy in a mid-size Midwestern city..

Ultimately, what his frustration with the NFL seems to add up to is the process of dehumanization that it entails. As an NFL player, you are expected to lose your individuality. It’s the flip side of one of the nicer things you could say about sports, specifically football, and especially the offensive line: it gives you a chance to be part of something larger than yourself. But you can say that about many things, and that’s what makes his dilemma so compelling, I think. It’s a ramped-up version of a very human problem.

Often, it seems like the cons outweigh the pros to staying in football for Anonymous. He feels like he should quit, and his hometown girlfriend certainly encourages him to do so. But, ultimately, he’s not Chris Borland, the pomising San Francisco 49ers linebacker who quit the NFL after just one year. Anonymous struggles to rationalize what keeps him playing, settling for a vague mixture of a love of playing and also a vague terror of deciding what he would do otherwise.

This all sounds pretty personal, but it doesn’t really answer what’s with the anonymity. That’s much easier to explain: he writes with the kind of honesty that makes the people around him look human. And, by “human,” I mean it makes the characters who populate this book–the general manager and owner, his coaches, his teammates, and even himself–look like flawed, silly, self-interested, narcissistic jackasses. He also captures their vulnerabilities and fears and jokes intended for private audiences. I mean, it’s kind of what happens when you write a memoir from any walk of life that isn’t overly sanitized for public consumption.

Anonymous is not overly self-serious, so it would feel off-putting to expect him to treat the rest of his world this way. You do get invested in his journey–from his status as ex-mama’s boy who struggles to move on after her death when was in junior high, to his cyclical relationship with his girlfriend, to his his love/hate relationship with his offensive line coach. It’ll matter to you, too, by the end, if you stick with the book–if you’re okay with all the cursing and lack of political correctness/general sense of propriety.

And, though I find the probing of human condition in those around us to be a fascinating and forgiving process lined with the potential for empathy, that’s cold comfort when you are routinely held up for public scrutiny as much as NFL players and coaches are. Especially when we fans and they themselves so often expect them to be more than human. And don’t even get me started on how the NFL is not big on the distractions that this book could generate with sufficient notoriety.

If you’re looking for a gritty exposé on the dark underbelly of the NFL, this book is probably going to waste your time. If you’re looking for a conflicted, fascinating memoir from the perspective of a specific (though representative) NFL player, this book is great. If you enjoy reading ESPN the Magazine or Peter King’s MMQB website, you will probably like this book. I know I did.

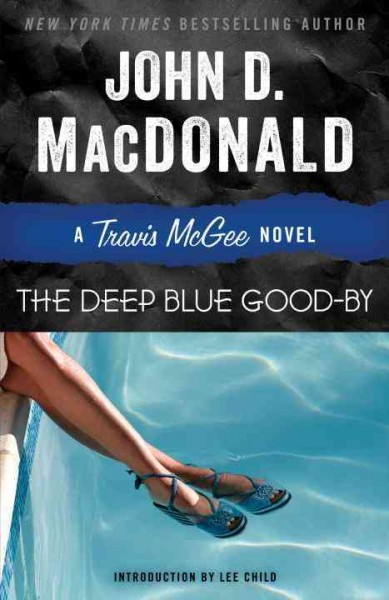

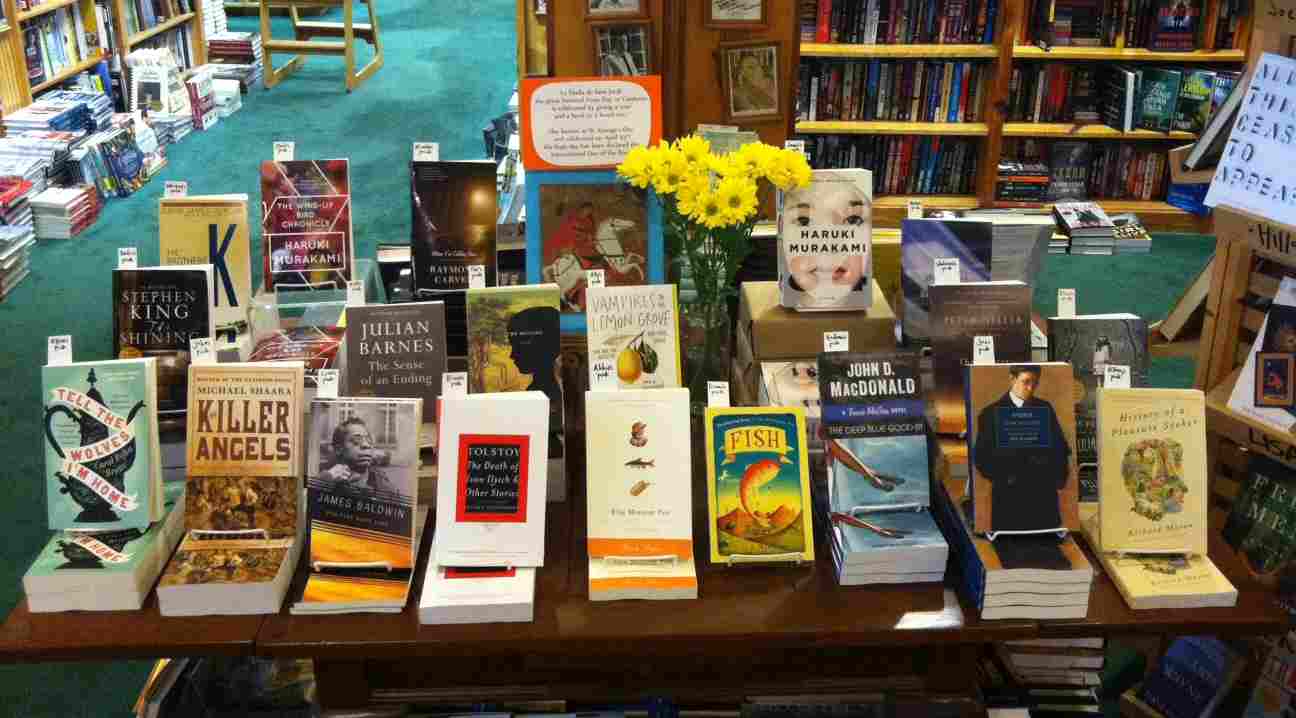

The Travis McGee novels (which can all be identified by the colors in their title, all the way to 1985’s elegiac Lonely Silver Rain) have tightly-constructed and entertaining plots, but it’s the little things that stick with you after you read them: McGee’s philosophical ruminations, proto-environmentalism, and general unease with adapting to modern life (even 50 years ago). The richly detailed settings of 1960s Fort Lauderdale, especially Bahia Mar, where McGee’s houseboat, The Busted Flush, is parked right next to the Alabama Tiger’s Perpetual Floating House Party. And, even though he is strangely missing from The Deep Blue Good-by, the person who outlasts any of McGee’s various lovers is Meyer, the bearded economist living about his yacht the John Maynard Keynes, who frequently plays Watson to McGee’s Sherlock.

The Travis McGee novels (which can all be identified by the colors in their title, all the way to 1985’s elegiac Lonely Silver Rain) have tightly-constructed and entertaining plots, but it’s the little things that stick with you after you read them: McGee’s philosophical ruminations, proto-environmentalism, and general unease with adapting to modern life (even 50 years ago). The richly detailed settings of 1960s Fort Lauderdale, especially Bahia Mar, where McGee’s houseboat, The Busted Flush, is parked right next to the Alabama Tiger’s Perpetual Floating House Party. And, even though he is strangely missing from The Deep Blue Good-by, the person who outlasts any of McGee’s various lovers is Meyer, the bearded economist living about his yacht the John Maynard Keynes, who frequently plays Watson to McGee’s Sherlock.

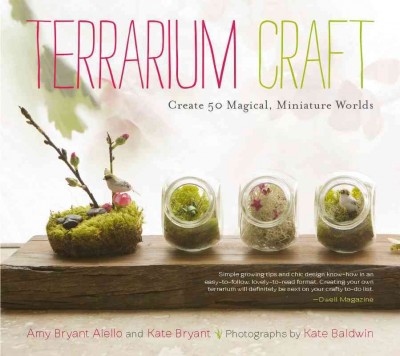

uch always love to make something, but I think the whole new life thing that comes along with spring really does something to me. A book I’ve been drooling over for quite some time now is The Modern Natural Dyer. Not only is it a gorgeous book, but it also tells you how to dye fibers with flowers, vegetables, and spices. Basically head on over to the grocery store and make a mess because I love to make a mess. It’s the cleaning up that presents a problem for me. This book has twenty projects for your home and your wardrobe, including knitting and sewing. Pretty amazing if you think about it. “Oh, why yes, I did make this! I dyed it as well. Eat your freaking heart out!!!” Next up on the docket we have Materially Crafted: A DIY Primer for the Design-Obsessed (that’s me). So this book’s projects are broken down into sections of spray paint, plaster, concrete, paper, thread, wax, wood, and the list goes on. I could definitely get into a modern looking concrete cake stand or some precious wax bud vases. There is more to come about this display, but I feel like I am close to losing all of you so I will leave you here

uch always love to make something, but I think the whole new life thing that comes along with spring really does something to me. A book I’ve been drooling over for quite some time now is The Modern Natural Dyer. Not only is it a gorgeous book, but it also tells you how to dye fibers with flowers, vegetables, and spices. Basically head on over to the grocery store and make a mess because I love to make a mess. It’s the cleaning up that presents a problem for me. This book has twenty projects for your home and your wardrobe, including knitting and sewing. Pretty amazing if you think about it. “Oh, why yes, I did make this! I dyed it as well. Eat your freaking heart out!!!” Next up on the docket we have Materially Crafted: A DIY Primer for the Design-Obsessed (that’s me). So this book’s projects are broken down into sections of spray paint, plaster, concrete, paper, thread, wax, wood, and the list goes on. I could definitely get into a modern looking concrete cake stand or some precious wax bud vases. There is more to come about this display, but I feel like I am close to losing all of you so I will leave you here Brundage takes you to when the Clares first met, and you soon realize that their marriage is not what it appears to be; it’s mostly thrown together because of Catherine’s pregnancy. They begin to move into the auctioned off farm house and meet their neighbors and George’s colleagues. The Hale brothers, the former residents of the home, start to come around and help with upkeep, and the youngest will sometimes babysit Franny, the Clares’ three-year-old daughter. The story is told from multiple points of view, switching from Catherine to one of the Hale brothers and then back to George. Brundage gives quite a few of the Clares new acquaintances chapters throughout the book and shows their perspectives of George and his wife. Most of them see the couple as happy and put together, but some see straight through the lies. As you move through these multiple viewpoints, pieces begin to fall into place, and many people are not at all what you expected.

Brundage takes you to when the Clares first met, and you soon realize that their marriage is not what it appears to be; it’s mostly thrown together because of Catherine’s pregnancy. They begin to move into the auctioned off farm house and meet their neighbors and George’s colleagues. The Hale brothers, the former residents of the home, start to come around and help with upkeep, and the youngest will sometimes babysit Franny, the Clares’ three-year-old daughter. The story is told from multiple points of view, switching from Catherine to one of the Hale brothers and then back to George. Brundage gives quite a few of the Clares new acquaintances chapters throughout the book and shows their perspectives of George and his wife. Most of them see the couple as happy and put together, but some see straight through the lies. As you move through these multiple viewpoints, pieces begin to fall into place, and many people are not at all what you expected.

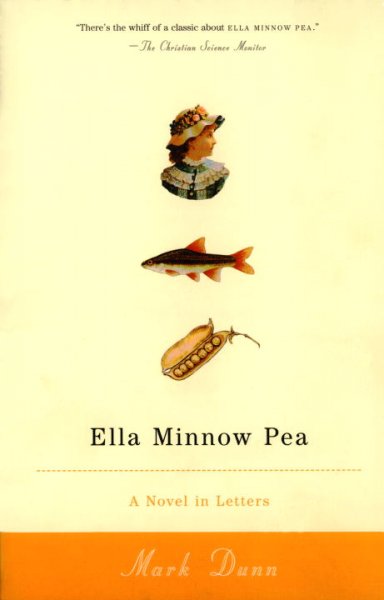

First off, the description of the night being a “black tarp” that’s held in place by stars is simply genius. Trust me: this will affect the way you look at the night’s sky from now on. And the way the poem shifts its (and our) focus from the sky to the lake in which this unnamed man is flinging his fishing net feels natural. This sky/lake relationship is maintained at the poem’s close when, as the threadfin fish slip out of the seine net, the lake is compared to a mirror that reminds us of “when/ this deep water was a sky.”

First off, the description of the night being a “black tarp” that’s held in place by stars is simply genius. Trust me: this will affect the way you look at the night’s sky from now on. And the way the poem shifts its (and our) focus from the sky to the lake in which this unnamed man is flinging his fishing net feels natural. This sky/lake relationship is maintained at the poem’s close when, as the threadfin fish slip out of the seine net, the lake is compared to a mirror that reminds us of “when/ this deep water was a sky.”

While I was working at the humane society, I was around about 150 animals every day. I currently have one dog, two cats, and one foster dog. So, right now I’m only around four a day. When I’m with my dog or cats, I’ll find myself wondering what they’re thinking about or trying to tell me (if that sounds weird….oh, well). BUT, don’t you fret; with Clark’s new book,

While I was working at the humane society, I was around about 150 animals every day. I currently have one dog, two cats, and one foster dog. So, right now I’m only around four a day. When I’m with my dog or cats, I’ll find myself wondering what they’re thinking about or trying to tell me (if that sounds weird….oh, well). BUT, don’t you fret; with Clark’s new book,

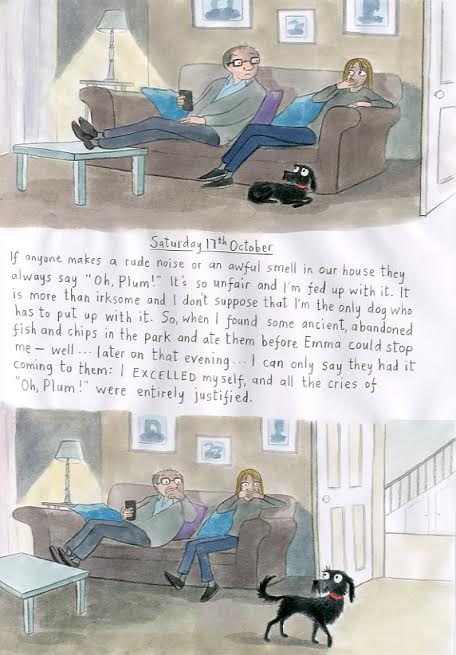

nicely you may ask for it back. That’s just how it is. Also, Plum would like for any and every dog owner to quit blaming their dogs for any rude noise or smell that occurs. It’s just simply not the dog….most of the time.

nicely you may ask for it back. That’s just how it is. Also, Plum would like for any and every dog owner to quit blaming their dogs for any rude noise or smell that occurs. It’s just simply not the dog….most of the time.

Johnny Anonymous, a white offensive lineman in the NFL who wishes to remain, well…anonymous, opens his book

Johnny Anonymous, a white offensive lineman in the NFL who wishes to remain, well…anonymous, opens his book