By Susan Cushman. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (January 12)

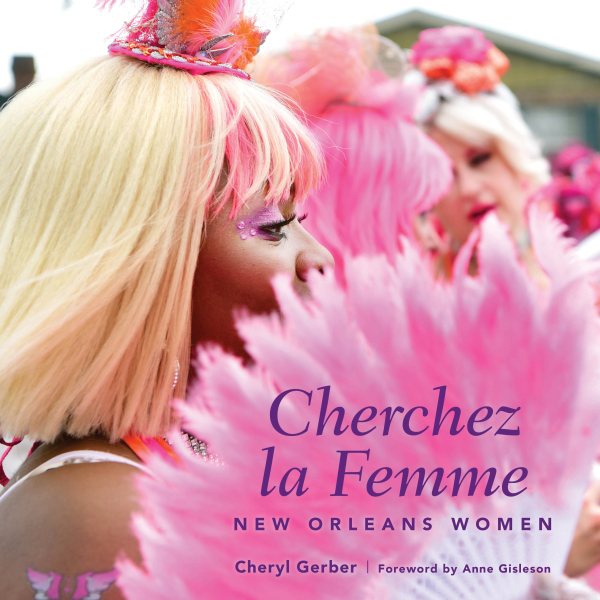

Inspired by the 2017 Women’s March in Washington, D.C., New Orleans native and documentary photographer Cheryl Gerber has, in her new book Cherchez la Femme: New Orleans Women, curated an incredible collection of over 200 color photographs and 12 essays, showcasing both famous and lesser-known New Orleans women. Gerber set out to show their “grit and grace” and their “beauty and desire,” and I believe she succeeded in a big way with this gorgeous large format hardcover masterpiece.

Inspired by the 2017 Women’s March in Washington, D.C., New Orleans native and documentary photographer Cheryl Gerber has, in her new book Cherchez la Femme: New Orleans Women, curated an incredible collection of over 200 color photographs and 12 essays, showcasing both famous and lesser-known New Orleans women. Gerber set out to show their “grit and grace” and their “beauty and desire,” and I believe she succeeded in a big way with this gorgeous large format hardcover masterpiece.

Cherchez la femme literally translates as “look for the woman.” In his 1854 novel The Mohicans of Paris, Alexandre Dumas repeats the phrase several times. Since then the French have often used it in a sexist manner, implying that women–or “the woman”–must be the cause of whatever problem is being described. It brings to mind Adam’s reply to God’s question concerning his transgression with the forbidden fruit; he blamed it on “the woman you gave me.”

In her homage to those women, Gerber has turned that phrase on its head, inviting the reader to look for the women who have made and are still making significant contributions to their colorful city.

My use of the word “colorful” is intentional. In the foreword, New Orleans native Anne Gisleson prepares us for the tour de force that Cherchez la Femme is–a tribute to the monumental achievements of colorful women and women of color.

Beginning with the Ursuline nuns and their beloved Lady of Prompt Succor who ran the hosptials and schools for people of all races as early as the War of 1812, and later as French baroness Macaela Pontalba fought to protect and rebuild the historic architecture of her beloved city. Gisleson introduces us to Henriette Delille–a free woman of color who started her won order to feed and educate the poor, since she wasn’t allowed to join the Ursulines.

Gerber’s loving tribute to chef Leah Chase (1923-2019) and Helen Freund’s essay about Chase in the culinary chapter set a celebratory tone for the stories that follow. Gerber organized these into topical chapters: Musicians, Business, Philanthropists and Socialites, Spiritual, Activists, Mardi Gras Indian Queens, Mardi Gras Krewes, Baby Dolls, Social and Pleasure Clubs, and Burlesque. The contributors include publishers, authors, historians, journalists, and educators.

Fifty years ago, the New Orleans-born gospel great Mahalia Jackson debuted at Jazz Fest. In her essay, Alison Fensterstock hails Jackson as “an artist whose powerful creative spark and spiritual passion shaped the sound not only of the city, but also of her nation.”

In her essay, Kathy Finn says that female entrepreneurs–including Voodoo practitioners, strippers, clothing and jewelry designers, and professional sports team owners–are “helping to ensure that the city” retains its unique character far into the future.”

Sue Strachan tells us about a bevy of female philanthropists, lobbyists, social columnists, and fundraisers who have “a passion for making the community a better place.”

The city of New Orleans–named for a young French girl who saw angels and saints and led France in a victory over England, “The Maid of Orleans,”–today “serves as the cauldron where these archetypal forms simmer together: the saints, the nuns, the witches, the mambo…a distinctively feminine spirituality…that runs through the streets…” Constance Adler found her true home there through a Voodoo priestess’ “gestures, words, and smoke at the altar.”

Katy Reckdahl shines a light on many women activists, showing us that “the tradition of resistance in New Orleans is particularly strong.”

Mardi Gras Indian Queens like essay contributor Charice Harrison-Nelson, also known as Maroon Queen Reesie, is one of 16 Indian Queens Gerber photographed for the book. Did I mention this city (and the book) is colorful?

While Krewes were male-dominted in the past, women have become “the architects of a new carnival experience,” as Karen Trahan Leathem explains in her essay.

Kim Vaz-Deville goes into more depth about the Baby Dolls, offering an opportunity for black women who were previously shout out of Mardi Gras. Gerber captures 14 of these dance groups in her amazing photographs.

Social and pleasure clubs keep the tradition of second-line parades alive. Karen Celestan explains in her essay: “The kinetic procession viewed on weekend streets in the Crescent City is nothing less than liquid muscle memory….It is fresh joyfulness, majestic, paying tribute to their ancestors.”

Gerber’s final chapter features an essay by Melanie Warner Spencer, who writes about the resurgence of burlesque. Today’s stars–like Bella Blue, Louisiana native and mother of two–are often trained in classic ballet. Blue is also headmistress of the New Orleans School of Burlesque. Spencer says burlesque “promotes a message of fun, fabulousness, confidence, and body positivity…keeping alive an art farm that is as much a part of the history of New Orleans as streetcars and beignets albeit a dash naughtier.”

“Fun and fabulousness” are also words I would use to describe Cherchez la Femme, a beautiful love letter to the women of New Orleans.

Jackson native Susan Cushman is editor of Southern Writers on Writing and two other anthologies. She is author of short story collection Friends of the Library, the novel Cherry Bomb, and the memoir Tangles and Plaques: A Mother and Daughter Face Alzheimer’s.

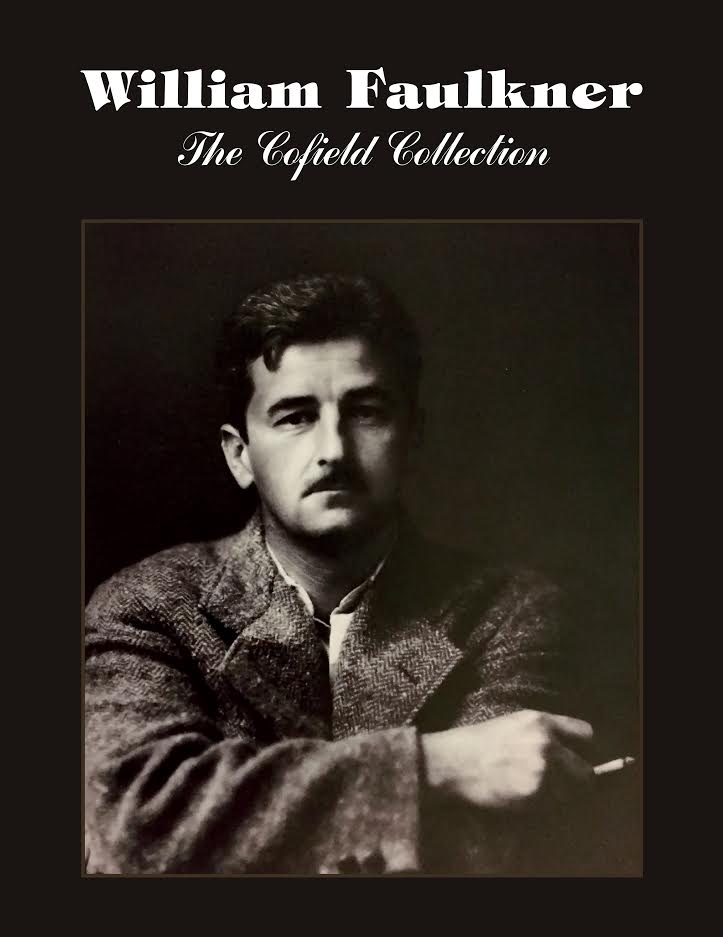

“It wasn’t easy to get a smiling photograph of William Faulkner!” That was the fond, exasperated comment of J.R. “Colonel” Cofield, the Oxford photographer in whose studio Faulkner sat for the portraits that graced the dust jackets of his novels.

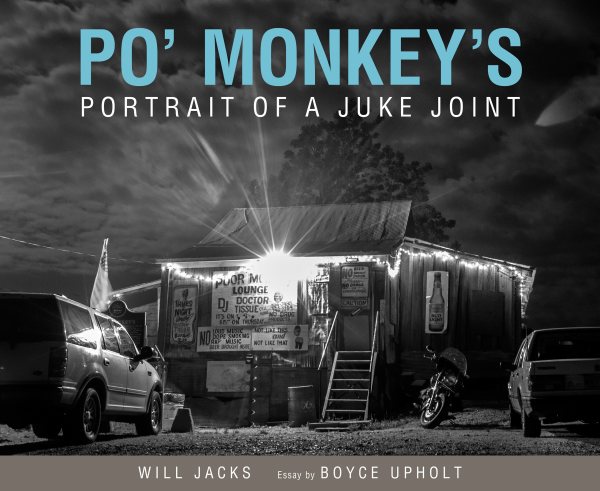

“It wasn’t easy to get a smiling photograph of William Faulkner!” That was the fond, exasperated comment of J.R. “Colonel” Cofield, the Oxford photographer in whose studio Faulkner sat for the portraits that graced the dust jackets of his novels. After decades of those-who-know-don’t-need-to-ask operation catering to locals in search of a Thursday evening respite, the establishment rose to prominence as white photographers and journalists enthralled by its authenticity brought news of its existence to their audiences, turning it into a must-see site for blues tourists traveling the Mississippi Delta.

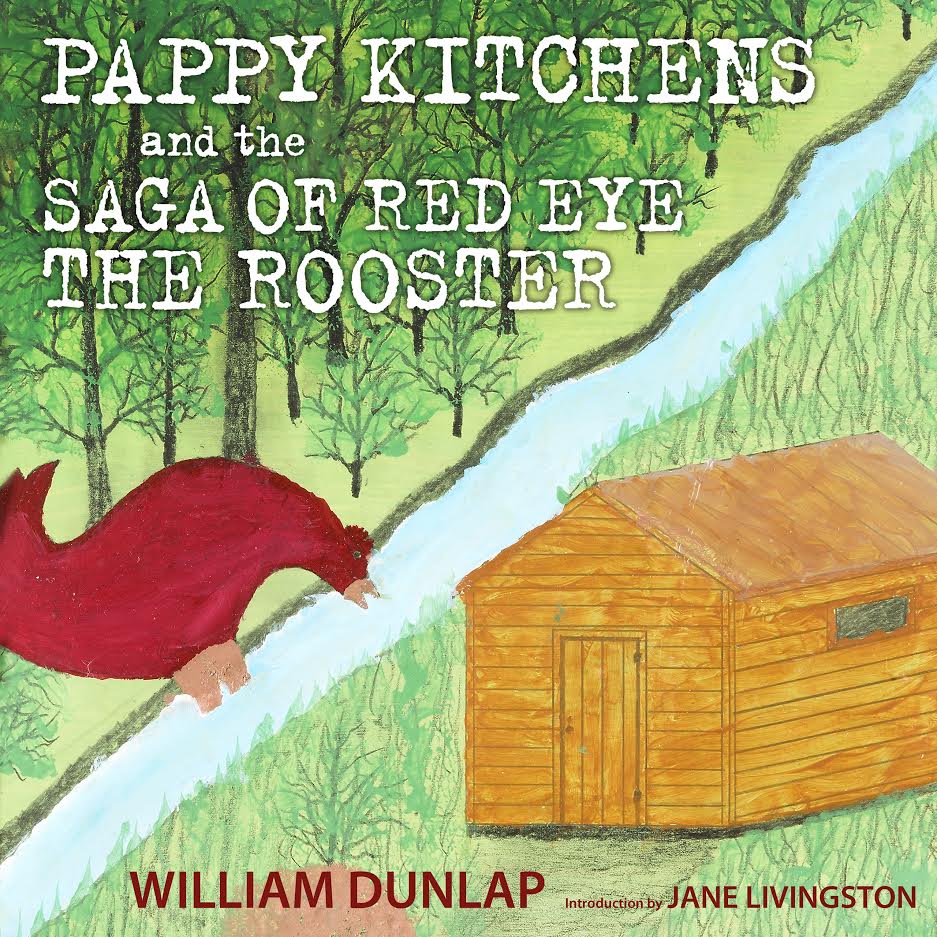

After decades of those-who-know-don’t-need-to-ask operation catering to locals in search of a Thursday evening respite, the establishment rose to prominence as white photographers and journalists enthralled by its authenticity brought news of its existence to their audiences, turning it into a must-see site for blues tourists traveling the Mississippi Delta. O.W. “Pappy” Kitchens was a distinctive Mississippi character. He was a building contractor and house mover, as well as an accomplished storyteller, who, after he sold his business and retired, discovered that he was an artist.

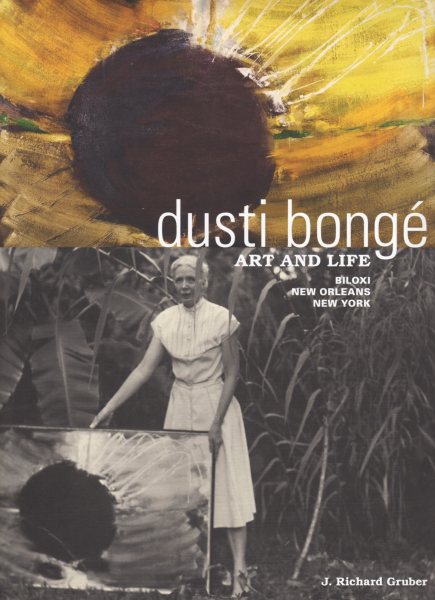

O.W. “Pappy” Kitchens was a distinctive Mississippi character. He was a building contractor and house mover, as well as an accomplished storyteller, who, after he sold his business and retired, discovered that he was an artist. In the interest of full disclosure, let me state that I know Rick Gruber, and I know him to be a scholar of the first order who has at his command more information about art of a southern nature than anyone alive. It is also worth noting that his prose is infinitely readable, unlike so many of those who write about art in a scholarly fashion.

In the interest of full disclosure, let me state that I know Rick Gruber, and I know him to be a scholar of the first order who has at his command more information about art of a southern nature than anyone alive. It is also worth noting that his prose is infinitely readable, unlike so many of those who write about art in a scholarly fashion.

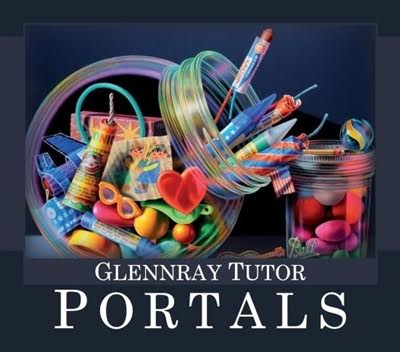

Oxfords’s Glennray Tutor–who has been cited as not only one of the world’s top hyperrealist artists, but also one of the three who actually began the movement–shares his visionary style developed over more than three decades in his debut album,

Oxfords’s Glennray Tutor–who has been cited as not only one of the world’s top hyperrealist artists, but also one of the three who actually began the movement–shares his visionary style developed over more than three decades in his debut album,

In

In

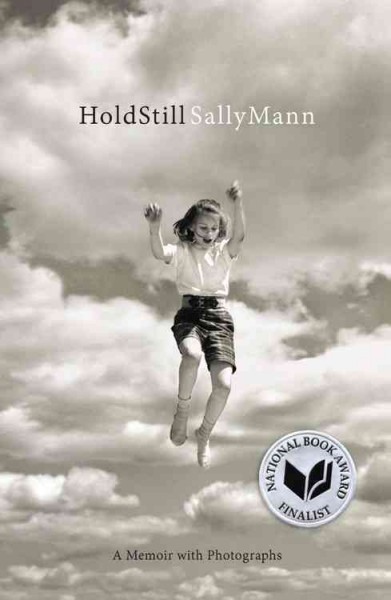

Just a week ago I realized that I could not have the woman I basically worship come to Lemuria without even reading her book. So I did it. I picked up the book I had treasured like a child for almost a year. This book has had permanent residence beside my bed in two different homes at this point. I can only blame putting it off for so long because of my own stupid fear. What if it wasn’t as good as I needed it to be? After all, she is human. She could get it wrong. Thankfully all that worrying was in vain because not unlike Patti Smith, Sally Mann is a Renaissance woman. And if I had looked a little more closely, I would have seen that Patti had even blurbed the damn thing on the back.

Just a week ago I realized that I could not have the woman I basically worship come to Lemuria without even reading her book. So I did it. I picked up the book I had treasured like a child for almost a year. This book has had permanent residence beside my bed in two different homes at this point. I can only blame putting it off for so long because of my own stupid fear. What if it wasn’t as good as I needed it to be? After all, she is human. She could get it wrong. Thankfully all that worrying was in vain because not unlike Patti Smith, Sally Mann is a Renaissance woman. And if I had looked a little more closely, I would have seen that Patti had even blurbed the damn thing on the back. And then we come to her writing about her work. Well I could read about that until I am I don’t know what. Immediate Family was the first body of work that I became familiar with of Sally’s, but it was her writing about Deep South that really resonated with me. Being a Mississippi delta girl and someone who is very connected to the land, I very much get what she was doing with this work. But I can honestly say I didn’t feel the images before as I do now. I am looking at those images in a completely different way now. In one part she says that the images look “breathed onto the plate.” If you haven’t read the book or aren’t familiar with her process, she is referring to the way the southern landscape and the light appear on a collodion plate. “Breathed onto the plate.” Now that is one of the loveliest things I’ve ever read, and it will always be with me.

And then we come to her writing about her work. Well I could read about that until I am I don’t know what. Immediate Family was the first body of work that I became familiar with of Sally’s, but it was her writing about Deep South that really resonated with me. Being a Mississippi delta girl and someone who is very connected to the land, I very much get what she was doing with this work. But I can honestly say I didn’t feel the images before as I do now. I am looking at those images in a completely different way now. In one part she says that the images look “breathed onto the plate.” If you haven’t read the book or aren’t familiar with her process, she is referring to the way the southern landscape and the light appear on a collodion plate. “Breathed onto the plate.” Now that is one of the loveliest things I’ve ever read, and it will always be with me.

uch always love to make something, but I think the whole new life thing that comes along with spring really does something to me. A book I’ve been drooling over for quite some time now is The Modern Natural Dyer. Not only is it a gorgeous book, but it also tells you how to dye fibers with flowers, vegetables, and spices. Basically head on over to the grocery store and make a mess because I love to make a mess. It’s the cleaning up that presents a problem for me. This book has twenty projects for your home and your wardrobe, including knitting and sewing. Pretty amazing if you think about it. “Oh, why yes, I did make this! I dyed it as well. Eat your freaking heart out!!!” Next up on the docket we have Materially Crafted: A DIY Primer for the Design-Obsessed (that’s me). So this book’s projects are broken down into sections of spray paint, plaster, concrete, paper, thread, wax, wood, and the list goes on. I could definitely get into a modern looking concrete cake stand or some precious wax bud vases. There is more to come about this display, but I feel like I am close to losing all of you so I will leave you here

uch always love to make something, but I think the whole new life thing that comes along with spring really does something to me. A book I’ve been drooling over for quite some time now is The Modern Natural Dyer. Not only is it a gorgeous book, but it also tells you how to dye fibers with flowers, vegetables, and spices. Basically head on over to the grocery store and make a mess because I love to make a mess. It’s the cleaning up that presents a problem for me. This book has twenty projects for your home and your wardrobe, including knitting and sewing. Pretty amazing if you think about it. “Oh, why yes, I did make this! I dyed it as well. Eat your freaking heart out!!!” Next up on the docket we have Materially Crafted: A DIY Primer for the Design-Obsessed (that’s me). So this book’s projects are broken down into sections of spray paint, plaster, concrete, paper, thread, wax, wood, and the list goes on. I could definitely get into a modern looking concrete cake stand or some precious wax bud vases. There is more to come about this display, but I feel like I am close to losing all of you so I will leave you here