By Allen Boyer. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (December 1)

“It wasn’t easy to get a smiling photograph of William Faulkner!” That was the fond, exasperated comment of J.R. “Colonel” Cofield, the Oxford photographer in whose studio Faulkner sat for the portraits that graced the dust jackets of his novels.

“It wasn’t easy to get a smiling photograph of William Faulkner!” That was the fond, exasperated comment of J.R. “Colonel” Cofield, the Oxford photographer in whose studio Faulkner sat for the portraits that graced the dust jackets of his novels.

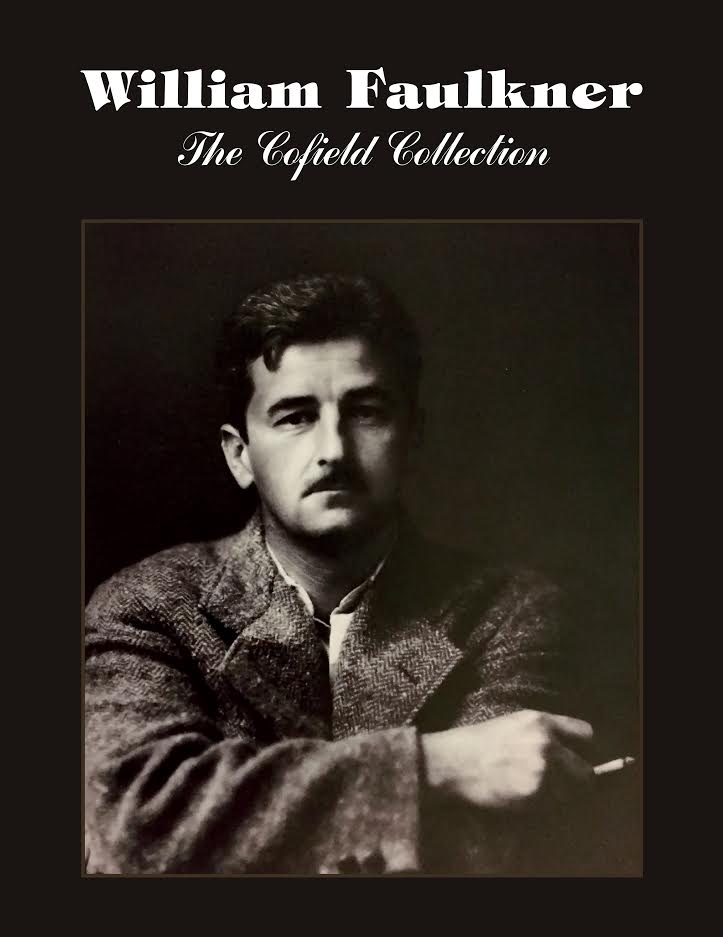

Dealing with William Faulkner was daunting. Yet Cofield endured and ultimately, he prevailed. He seldom saw Faulkner smile, but he captured striking images of the man. Those portraits, with other photos taken or collected by the Cofield family, supply the heart of William Faulkner: The Cofield Collection–published in 1978, now brought back to print.

Cofield first photographed Faulkner when he published Sanctuary, in 1931. Faulkner was thirty-three, a handsome young author with a tweed jacket and a cigarette. Late in life, when pressed by friends in Virginia, he posed in a fox-hunting outfit, with top hat and riding boots and blazing red huntsman’s coat. Other times he was indifferent; he would sit for Cofield wearing a three-piece suit or a simple blue work shirt.

As well as Faulkner, this book covers the postage-stamp of native soil about which he wrote. Field hands work mules, and farmers sell produce from trucks parked on the Oxford Square. Cotton wagons crowd the lot outside the gin. Barnstormers pose beside grass airstrips. Schoolchildren line up, some outside the Oxford Graded School, others on muddy lawns out in the county. A string band warms up the crowd for a speech by youthful Senate candidate John Stennis.

Some pictures have the glossy look of publicity shots. Years after he had won the Nobel Prize for literature, Faulkner posed at a Memphis preview of Land of the Pharaohs. He had a screenwriter’s credit on the picture, and it was a film by Howard Hawks, the director who took Faulkner dove-hunting with Clark Gable. Faulkner’s own favorite photo looks like something from Hollywood, a studio close-up straight out of film noir.

Faulkner summoned Colonel Cofield to Rowan Oak to record his celebrated costume-party hunt breakfast, that Sunday morning in May 1938. He called him back for two weddings, his daughter’s and his niece’s, and at those receptions Cofield caught him smiling.

Some of Faulkner’s past is dead–very clearly past. There are images here from Life Magazine and the Memphis Press-Scimitar. As a teenager, Faulkner often rode the train to Taylor and hiked back along Old Taylor Road, then a red-dirt track, now choked with the cars of Ole Miss student traffic. Black men and women appear on the edges of their white employers’ family portraits. (John Cofield, grandson of Colonel Cofield, whose internet collections preserve his hometown’s history, energetically documents the past of both black and white communities. Forty years ago, this was harder.)

In Faulkner’s fictional Yoknapatawpha County, the Sartoris family seems modeled on Faulkner’s own relations. But, ironically, there is much of the novelist in a different character, strong-willed black tenant farmer Lucas Beauchamp. Beauchamp is a match for Faulkner in independence and a subdued haughty knightliness, a taciturnity shaped by battles with misfortune. Beauchamp’s face, Faulkner wrote, “was not sober and not grave but wore no expression at all.” Can the same distant unreadable expression be seen in these pages? For in nearly every photograph, studio portrait or snapshot alike, Faulkner’s gaze is similar–serious, reserved, never quite directly into the camera. Cofield knew that expression well. Quoting Kipling, he wrote: “‘No price is too high to pay for the privilege of owning yourself.’ Bill Faulkner lived up to this principle to a T.”

Some of these images will be familiar. It was this book that made them well-known. Eudora Welty praised the original edition of “The Cofield Collection.” “These photographs,” she wrote, “eloquently tell us what no voice now can tell, what no words are likely to express so clearly and intimately about William Faulkner’s life.” Miss Welty was no mean photographer herself, and her judgment still holds true.

Allen Boyer lives and writes on Staten Island. He grew up in Oxford, where Colonel Cofield took the Boyer family’s portraits every year.

Lawrence Wells, the editor of The Cofield Collection, will be at Lemuria on Saturday, December 7, from 1:00 to 2:00 to sign copies.

Comments are closed.