Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (November 5)

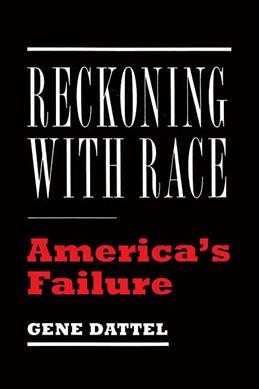

Cultural and economic historian Gene Dattel, who grew up in the small Mississippi Delta town of Ruleville, tackles questions about what he calls “America’s most intractable problem–race”–up close and in depth in his newest book, Reckoning with Race: America’s Failure (Encounter Books).

Cultural and economic historian Gene Dattel, who grew up in the small Mississippi Delta town of Ruleville, tackles questions about what he calls “America’s most intractable problem–race”–up close and in depth in his newest book, Reckoning with Race: America’s Failure (Encounter Books).

The biggest and most necessary part of bridging the racial divide, he said, is “economics–which means jobs,” a goal he believes is possible with what he calls “the right kind of assimilation.” To Dattel, that means avoiding what he believes is a harmful separatism while at the same time allowing for full expression of one’s cultural heritage.

Dattel’s lifelong interest in racial history, and its ties to economic history and colonial nationalism, was launched in the early 60s when he was entering Yale University at the same time James Meredith was entering Ole Miss.

After his early years in Ruleville, located in what he calls “the heart of the majority-black cotton country of the Mississippi Delta,” he graduated from Yale, and then Vanderbilt University Law School. Of his 21-year career in finance as a managing director at Salomon Brothers and Morgan Stanley, 15 were spent in London, Hong Kong, and Tokyo. He has done advisory work for the Pentagon, major financial institutions, and cultural organizations from the New York Historical Society to the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum.

His previous books include Cotton and Race in the Making of America and The Sun That Never Rose.

What prepared you to write this book, (as in, I’m curious–what exactly is a “cultural historian,” and how did you become one?) and what do you hope your book will accomplish?

The small-town dynamic of my youth mean that I had to adjust to people–old/young, middle class/poor, black/white–regularly. Beginning at age 13, I worked in my family’s dry goods store on Saturday night when most of the customers were black. I entered Yale at the same time James Meredith integrated Ole Miss. This triggered my profound interest in racial history, economic history, and colonial nationalism.

A career in finance brought home the importance of economics in the lives of people. My 11-year stay in Japan was transformative; there, I observed the first major economic challenge to the United States by a non-white, non-Western nation. For eight years, I performed a “Parallel Lives” Program with black author (and businessman” Clifton Taulbert about my growing up Jewish and his growing up black in the Mississippi Delta in the 1950s. My book Cotton and Race in the Making of America (2009), a description of the fateful intersection of the power of cotton and the African-American experience, was the stepping stone to Reckoning with Race.

My definition of a cultural historian: one who examines the impact of a broad range of topics–literature, art, movies, music, tradition, communication, values, rhetoric, humor, and fusion in a society. It is my sincere hope that this book contributes to a frank discussion about the hardest of all hard topics in America–race. I believe our goal should be to concentrate on access for the mass of blacks into the American economic mainstream.

In your book, you present a great deal of historical research that most of us never heard in our school history classes about the open hypocrisy of Northern and Midwestern states–dating back as far as the 1700s–of extreme racist attitudes toward blacks. Instead, the history that has captured the nation’s interest has, for the most part, emphasized the racial atrocities of the South. Why has this discrepancy largely remained a well-kept “secret”?

One has only to look at the quotes at the opening of the book’s chapters to recognize how white Northern racial attitudes have frequently been overlooked:

- White abolitionists “best love the colored man at a distance.” – Samuel R. Ward, Black Abolitionist, 1840s

- No free Negro, or Mulatto, not residing in this state at the time of this constitution shall come, reside, or be within this state. – Oregon State Constitution, 1857

- The New York Times, Feb. 26, 1865, in the text: “The negro race…would exist side by side with the white for centuries being constantly elevated by it, individuals of it rising to an equality with the superior white race.”

The white North has almost no exposure to its true historical racial attitudes. White Northern racial hypocrisy and self-righteousness has resulted. Historians extol the abolitionists but neglect the anti-black attitudes that doomed Reconstruction, created a containment policy of keeping blacks in the South, and trapped them in combustible urban ghettos. The drama of the civil rights movement in the 1960s was particularly visual and suited for television; millennials have seen countless clips of Birmingham hoses and dogs, etc. I have found that “going local” is effective in creating awareness for Northern audiences. When in Connecticut, include Connecticut’s past.

You state that, despite decades of political advancement, economics gains and the passage of civil rights legislation, “the practical task facing America is the economic elevation of the black community–desperately for the underclass and significantly for the fragile (but growing) middle class.” To that end, you emphasize the importance of personal responsibility and assimilation into American society. Explain why you believe this idea is so important.

America’s unique strength, its ability to foster the “right kind” of assimilation, allows its people to retain their cultural heritage. We are the only grand experiment of a multiethnic country that does not resort to tribalism. At the same time, we have seen no successful large scale self-sufficient economic group within America, able to function outside the economic mainstream. The acceptance of common values–color-blind middle-class norms–is a prerequisite for mass entrance into the economic mainstream.

In a competitive global marketplace, individuals must aspire to resiliency, a byproduct of personal responsibility.

You cover many government programs that have been implemented through the years to help African-Americans raise their standards of living, often with little progress. Why do you think it’s been so difficult to find lasting solutions toward economic progress?

Gene Dattel

Large government programs are plagued by bureaucracy, inefficiency, and most importantly, lack of accountability. I would argue, if a program is not working, change it or reduce it; if a program is working, expand it. I describe several small programs that are successful but cannot be replicated on a mass scale.

We need to understand and speak about the currently taboo topics of black culture and structure. The only way to move forward economically is to develop viable structures for family, church, and community. Education, the portable credential for employment, largely depends on these influences. Education provides the skill set and thought process for success. Or, in the words of New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker: “My mom and dad were constant mentors, my first and greatest teachers….[From my father] I learned the connection between hard work, discipline, and reward.”

Part of America’s problem in finding racial unity, you say, has been a “hypersensitivity” to real or perceived “slights” that seem to be arising more frequently, especially on college campuses. Why is this, and how can these be dealt with constructively?

Today’s iteration of multiculturalism fosters and encourages differences, to the detriment of what Americans have in common. Our inability to discuss real or perceived sensitive topics further inhibits dialogue and promotes separatism. Greater contact and discussion in a responsible, objective way is the best way to achieve trust. College is supposed to be the proper venue for challenging and preparing students for life and exposing them to a diversity of ideas. The interaction with different opinions promotes resiliency and should be pursued on an individual basis.

Despite hopes that an Obama presidency would help heal some racial divides, you state that “racial divisiveness is more evident now than it was when Obama took office.” To what do you attribute this change?

The racial divide had already been set in motion before the Obama presidency. Powerful forces–multiculturalism, frustration at the ineffectiveness of many programs, social media, separatism as expressed in identity politics, economic recession with a weak recovery, and the lack of a frank racial discussion–were at work. President Obama’s leadership could not produce the necessary unity given these factors.

You speak of a racial mindset in this country that seems to be heading more toward separatism than the defining goal of integration in the ’60s. Explain what that ultimately means, and what your hopes are for our future.

As of the end of 2016, the overall numbers for black progress in education and economic well-being were disheartening. The poverty level of blacks has remained three times that of white for the last 45 years. Also, 32.9 percent of black children under the age of 18 live in poverty. Only 38.7 percent of black children under 18 live in a two-parent family. Black Americans’ college majors, according to a 2016 Georgetown University study, “tend to be low earning.”

As we move int a stage of self-imposed, heightened racial identity, the goals of integration and assimilation become loaded terms with negative connotations. This separatism is highly detrimental in accessing a proper education, combating poverty, and attaining economic parity.

As for the future, we must remember America’s strength. Where else could a man, whose father was Kenyan and whose mother was a white American, become president?

Gene Dattel will sign copies of Reckoning with Race on Monday, November 13, at 5:00 p.m. at Lemuria.

The micro-memoir, she has said, “combines the extreme abbreviation of poetry, the narrative tension of fiction, and the truth-telling of creative nonfiction,” in works that include “memories, quirky observations, tiny scenes, (and) bits of overheard conversations that, with the surrounding noise edited out, reverberate.”

The micro-memoir, she has said, “combines the extreme abbreviation of poetry, the narrative tension of fiction, and the truth-telling of creative nonfiction,” in works that include “memories, quirky observations, tiny scenes, (and) bits of overheard conversations that, with the surrounding noise edited out, reverberate.”

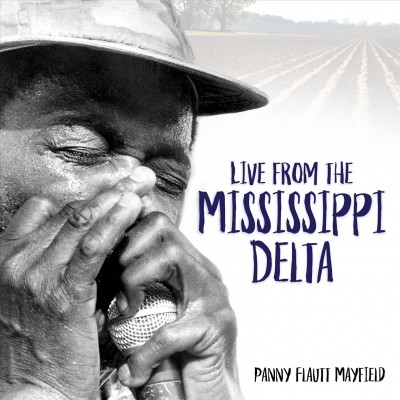

While the Coahoma County seat may not be a booming metropolis, the camera-wielding Mayfield frequently found herself in the right place at the right time, during culturally significant events and times over the past 30 years. Her casual stream-of-consciousness photo journal lets the reader in on the energy, with the perspective only a local could provide.

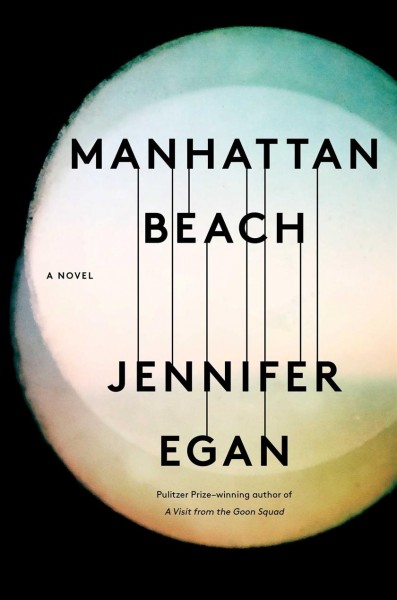

While the Coahoma County seat may not be a booming metropolis, the camera-wielding Mayfield frequently found herself in the right place at the right time, during culturally significant events and times over the past 30 years. Her casual stream-of-consciousness photo journal lets the reader in on the energy, with the perspective only a local could provide. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jennifer Egan’s newest release

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jennifer Egan’s newest release

It’s nice of you to ask. And, I promise you, I’m truly thankful for the people who invest in reading this novel once–that’s already a gift for a writer, and I ask no more. I can tell you that I worked hard to build a book you could just sit down and read, a linear novel that also happens to wrestle with age-old conflict and has many different plot lines, all running concurrently.

It’s nice of you to ask. And, I promise you, I’m truly thankful for the people who invest in reading this novel once–that’s already a gift for a writer, and I ask no more. I can tell you that I worked hard to build a book you could just sit down and read, a linear novel that also happens to wrestle with age-old conflict and has many different plot lines, all running concurrently.

In her newest novel,

In her newest novel,

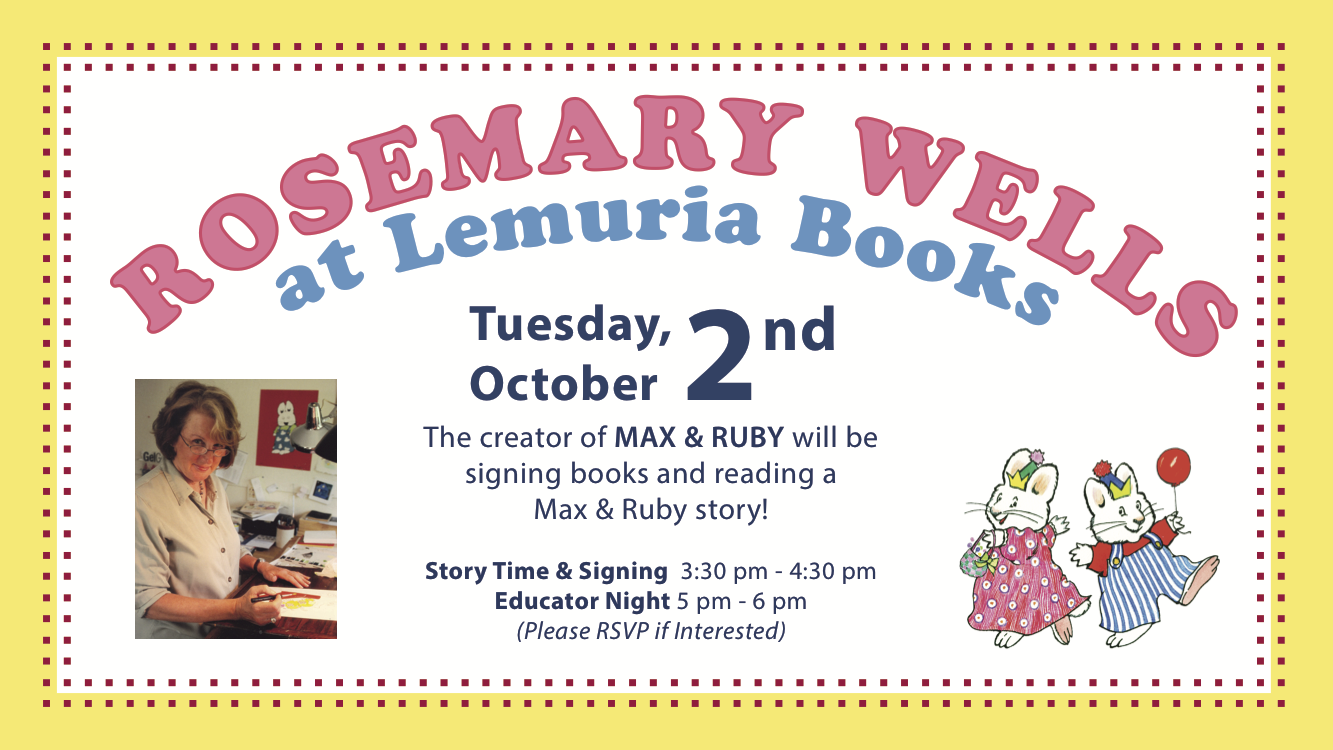

Their creator, Rosemary Wells, has been writing and illustrating books for over 45 years. She began working in publishing as a book designer for seven years. All through her writing and illustrating career, from her picture books to her young adult novels, Rosemary Wells advocates for children’s literacy wherever she goes. Born in New York City and raised in rural New Jersey, she now resides in Connecticut.

Their creator, Rosemary Wells, has been writing and illustrating books for over 45 years. She began working in publishing as a book designer for seven years. All through her writing and illustrating career, from her picture books to her young adult novels, Rosemary Wells advocates for children’s literacy wherever she goes. Born in New York City and raised in rural New Jersey, she now resides in Connecticut. My equally favorite character is Yoko. My next book is another Felix and Fiona melodrama friendship book from Candlewick. And next year, I have a book from Macmillan that introduces new characters, Kit and Kaboodle, twin pussycats and their little nemesis, Spinka, the mouse.

My equally favorite character is Yoko. My next book is another Felix and Fiona melodrama friendship book from Candlewick. And next year, I have a book from Macmillan that introduces new characters, Kit and Kaboodle, twin pussycats and their little nemesis, Spinka, the mouse.

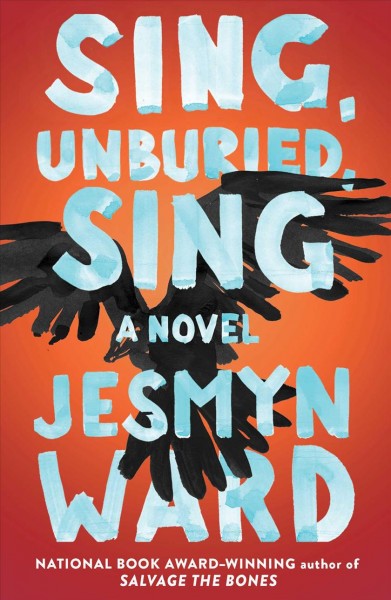

Jesmyn Ward’s

Jesmyn Ward’s