Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (January 7)

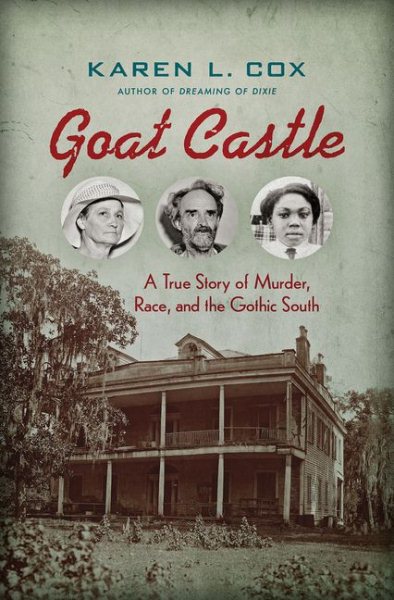

Goat Castle: A True Story of Murder, Race, and the Gothic South (University of North Carolina Press) uncovers the details of what came to be the highly sensationalized case of the 1932 murder of Jennie Merrill, a wealthy white Natchez woman who was killed during an attempted robbery of her antebellum home.

The book, which documents the obvious racial injustice with which the case was handled by local officials, gained national attention because of the eccentric lifestyle of initial suspects Richard Dana and Octavia Dockery, who lived in a decaying antebellum home overrun with crumbling furnishings, pervasive filth–and a pen of goats, among many other animals.

The book, which documents the obvious racial injustice with which the case was handled by local officials, gained national attention because of the eccentric lifestyle of initial suspects Richard Dana and Octavia Dockery, who lived in a decaying antebellum home overrun with crumbling furnishings, pervasive filth–and a pen of goats, among many other animals.

Emily Burns, an African-American domestic worker and Natchez resident who unwillingly found herself at the scene of the crime, was unjustly tried and convicted of the murder, and sentenced to life imprisonment at Parchman Penitentiary.

It was award-winning author Karen L. Cox, a history professor at University of North Carolina at Charlotte, who came across the story when she was conducting research for another book at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in Jackson.

Karen L. Cox

A native of West Virginia, Cox said her ties to Mississippi go back to when she first arrived in Hattiesburg to pursue her doctorate degree at the University of Southern Mississippi in 1991.

“There’s hardly been a year that I haven’t been back to the state to work on a research project,” she said. “After writing Goat Castle, I fell in love with Natchez and made good friends there.”

Cox, who teaches courses in American history and culture, also authored Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture, which won the Southern Association for Women Historians’ Julia Cherry Spruhill Prize; and Dreaming of Dixie: How the South Was Created in American Popular Culture. She is also editor of Destination Dixie: Tourism and Southern History.

As a distinguished historian widely recognized for her knowledge of the American South, Cox has written op-eds for The New York Times, The Washington Post, CNN, and The Huffington Post, and she has been interviewed by the Los Angeles Times, Newsweek, The Daily Beast, The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, and numerous other American newspapers, as well as papers in Germany, Denmark, Ireland, and Japan. She has also appeared on numerous television news outlets around the country, as well as the BBC.

How did you learn about this case, and why did you decide to write this book about it?

I learned about this case while working in the State Archives in Jackson. I was researching a previous book, which included the tourism generated by the Natchez Pilgrimage, when Clinton Bagley–a longtime historian/librarian at the Archives–told me that I should be looking at Goat Castle. As soon as I learned the barest of information on the story, I instinctively knew I’d write this book. It has so many layers to it and the “characters” are real. The truth is really stranger than fiction.

The investigation after the crime revealed that Dana and Dockery, white neighbors of Merrill’s, had plotted with George Pearls, an African-American, to rob Merrill’s home. But things wen terribly wrong, and Merrill was shot during the attempted robbery. After Pears was soon killed by an Arkansas policeman for an unrelated incident, an innocent black woman, Emily Burns, would ultimately be charged with the murder and imprisoned. The book states that the murder had become national news within less than 48 hours. Why was this?

Why it became national headlines so swiftly had to do with Jennie Merrill’s status as a descendant of planter aristocracy and being the daughter of Ayres Merrill, Jr., who was the former Belgian ambassador. Yet, within a week the story became less about her death and more about her eccentric neighbors, Dick Dana and Octavia Dockery. They, too, were from elite Southern families, but in 1932 lived in absolute squalor at their home Glenwood, which the press nicknamed “Goat Castle” since the pair kept a pen of goats inside the house.

The news coverage after the murder seems to have focused much more on the strange, eccentric lifestyle of Dockery and Dana than it did on the fact that a murder had been committed and Burns’ future was at stake. Please describe the public’s obsession with “Goat Woman” and “Wild Man,” and the press’s fascination with keeping the story focused on their “Old South” heritage–even as Burns remained in prison.

In addition to the squalor, the press nicknamed Dick Dana the “Wild Man” and, it seems, needed to give one to Octavia Dockery as well. She became the “Goat Woman.” The press was obsessed with what it saw as the decline of the Old South as seen in the lives of Dana and Dockery–the shocking contrast between the grandeur of the Old South and what appeared to be a Gothic novel come to life. This obsession resulted in a tourist trade to go to Natchez to see the house and the odd couple who lived there. It should be no surprise that little attention was paid to Emily Burns, a black domestic. Jim Crow justice meant that she was assumed to be guilty.

This book is well-documented, with 20 pages of notes. It seems that the research must have been painstaking, as you include a great deal of description about the city of Natchez, its crumbling antebellum homes at that time–and, just 70 years after the Civil War had ended, the mindset of the descendants of those who had fought in the Civil War and those who had been enslaved. How did you approach the research for this material, and how long did it take?

The timeline of the research looks like it took me five years (2012-2017), but it’s important to note that as a professor of history, I am also teaching classes, grading papers, going to meetings, etc. So, I’d have to plan research trips to Jackson, Natchez, and even Baton Rouge–a week here and a week there. Fortunately, I had a sabbatical that allowed me to write full time beginning in the fall of 2015. I wrote the book in about seven months. It went through a few months of editing and then was submitted in 2016. It takes about a year after submission for a book to come out.

Please describe the run and filth that Dockery and Dana lived in–along with ducks, geese, chickens, cats, dogs, and of course, the goats–and explain how they actually profited off of their eccentric lifestyle.

I’d rather that people read the book for those descriptions. They profited off of their notoriety by selling tickets to tour the grounds. There was a second charge to enter the house, where Dick Dana played piano. The pair also went on a tour of towns in Mississippi and Louisiana and appeared on stage as the “Wild Man” and “Goat Woman” of Goat Castle.

The city of Natchez was not fond of the publicity brought on by the trial at that time, but it was a boon for tourism.

How did the city deal with this circus of a crime story invading it on a national scale?

It’s not clear how the city of Natchez dealt with it. Certainly, local restaurants benefited. People would also tour other houses while in Natchez. On the one hand, there was profit to be made. On the other, it had become an embarrassment. So, the best way to deal with it was not to talk about it publicly.

What can we learn today from this story of criminal injustice 85 years ago–as a state and as a nation?

What is evident in this story is that the double standard of justice that sent an innocent black woman to prison still exists. Octavia Dockery’s fingerprints were found inside of Merrill’s home, not Burns’. Yet Dockery got to go home. Also, 85 years late, it’s still true that the majority of women sent to prison are women of color, especially African-American and Hispanic women.

Do you have other writing projects in mind that you can share with us?

I’m still trying to figure that out. Goat Castle only came out in October and I’ve still got book events coming up. I’ll be back in Natchez in February for the Literary and Cinema Celebration, which will be focused on Southern Gothic. I’m also going to be in New Orleans in march for the Tennessee Williams Literary Festival. My guess is that my next project will include Mississippi, as all of my books have done.

For many outdoors enthusiasts in Mississippi, Dorothy Shawhan’s book

For many outdoors enthusiasts in Mississippi, Dorothy Shawhan’s book  What began for Lyon as a doctoral dissertation while he was a history student at Ole Miss more than a decade ago eventually resulted in his debut book, which unfolds in meticulous detail why activists and students at Tougaloo College acted on what they believed was a necessary element in advancing their goal of racial integration in the capital city.

What began for Lyon as a doctoral dissertation while he was a history student at Ole Miss more than a decade ago eventually resulted in his debut book, which unfolds in meticulous detail why activists and students at Tougaloo College acted on what they believed was a necessary element in advancing their goal of racial integration in the capital city.

Addressing the Aug. 4, 1932, murder of Natchez heiress Jennie Merrill at her antebellum home Glenburnie, Cox peels back the layers of sensationalism surrounding the case to reveal the hard truths of racism and Jim Crow justice of the time.

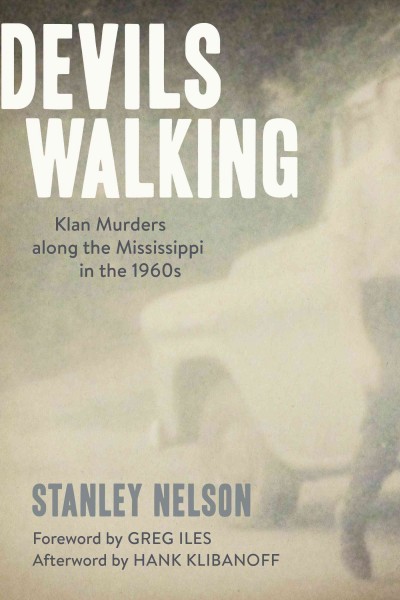

Addressing the Aug. 4, 1932, murder of Natchez heiress Jennie Merrill at her antebellum home Glenburnie, Cox peels back the layers of sensationalism surrounding the case to reveal the hard truths of racism and Jim Crow justice of the time. But it was Nelson’s tough investigative reporting that led to his book,

But it was Nelson’s tough investigative reporting that led to his book,

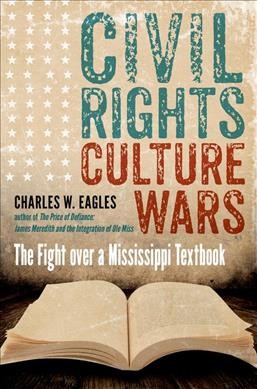

Not until 1980 were Mississippi high schools allowed to use a textbook that accurately and dispassionately covered the entire history of the state, complete with the horrors of slavery, the motives behind the Civil War, the value of Reconstruction, and the triumphs of the civil rights movement.

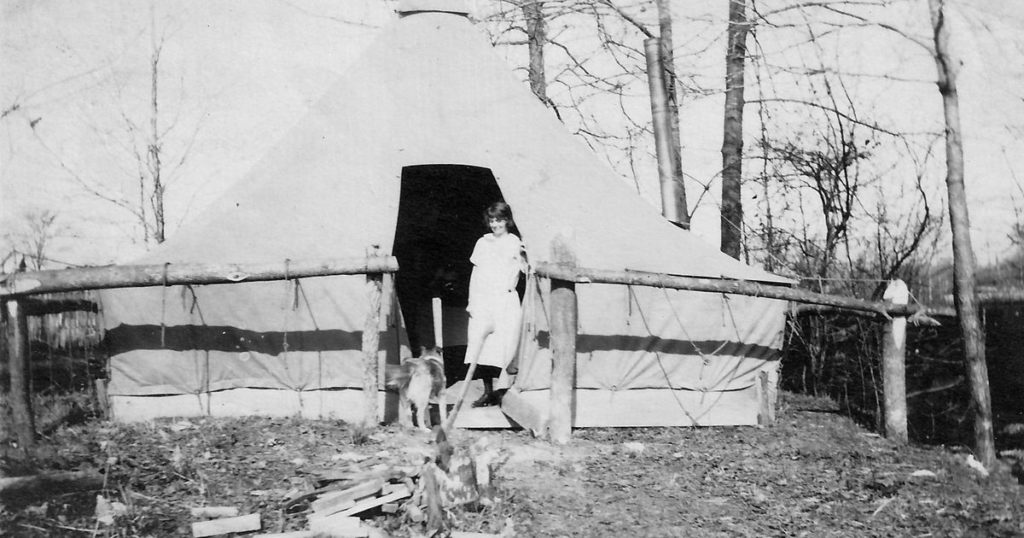

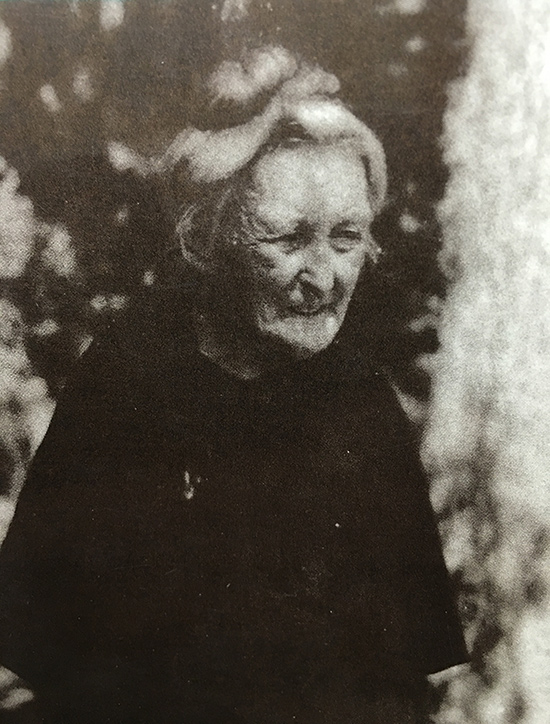

Not until 1980 were Mississippi high schools allowed to use a textbook that accurately and dispassionately covered the entire history of the state, complete with the horrors of slavery, the motives behind the Civil War, the value of Reconstruction, and the triumphs of the civil rights movement.  Mary Mann Hamilton was a remarkable women who was encouraged to write down her life as a female pioneer. Hamilton was born in 1866 and passed away in 1936. It was later in her life that she began to write down her experiences of “taming the American South”– she writes about living through floods, fires, tornadoes, and her husband’s drinking. An early draft of

Mary Mann Hamilton was a remarkable women who was encouraged to write down her life as a female pioneer. Hamilton was born in 1866 and passed away in 1936. It was later in her life that she began to write down her experiences of “taming the American South”– she writes about living through floods, fires, tornadoes, and her husband’s drinking. An early draft of

So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed

So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed The Great Beanie Baby Bubble

The Great Beanie Baby Bubble Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans

Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of Elements

The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of Elements Dispatches from Pluto: Lost and Found in the Mississippi Delta

Dispatches from Pluto: Lost and Found in the Mississippi Delta

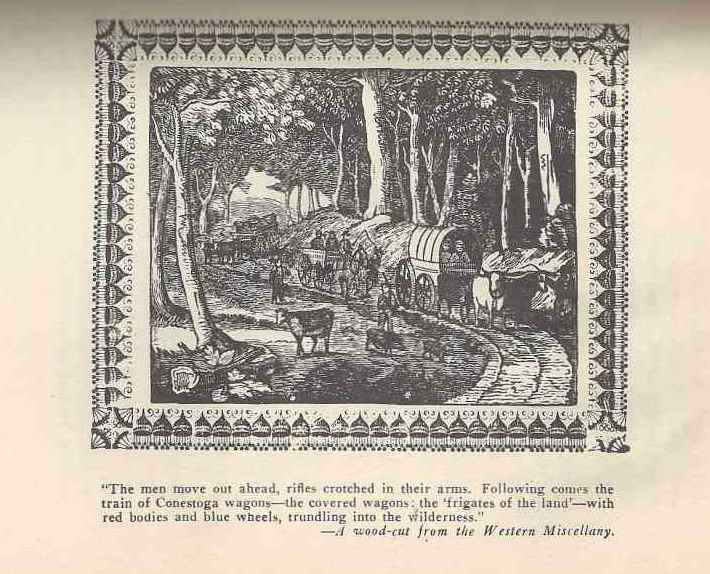

Coates’ list of sources are as equally intriguing as the entire book: Fulkerson’s “Early Days in Mississippi” (1885) is cited as an “excellent book of gossip”; “Ashe’s Travels in America” (1808) is noted as a “very interesting chronicle of an astonished Englishman, on a trip down to the Mississippi”; and Rothert’s “The Outlaws of Cave-in-Rock” (1924) is credited as a major source for the book.

Coates’ list of sources are as equally intriguing as the entire book: Fulkerson’s “Early Days in Mississippi” (1885) is cited as an “excellent book of gossip”; “Ashe’s Travels in America” (1808) is noted as a “very interesting chronicle of an astonished Englishman, on a trip down to the Mississippi”; and Rothert’s “The Outlaws of Cave-in-Rock” (1924) is credited as a major source for the book.