Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (December 30)

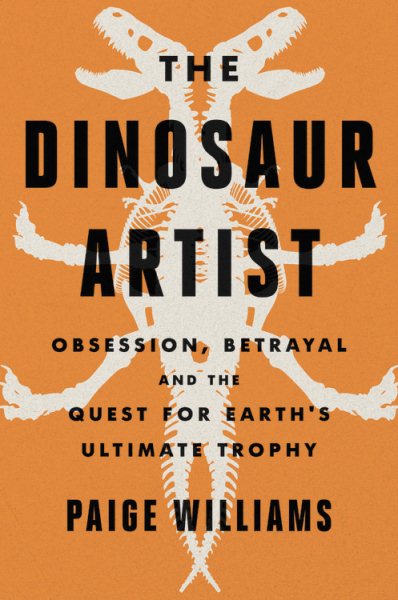

New Yorker Magazine staff writer and Mississippi native Paige Williams makes her book debut with a fascinating tale of the divided and sometimes dangerous world of fossil hunting, as she meticulously investigates the case of a rare and immense dinosaur skeleton that found its way from Mongolia to a Manhattan auction.

The ever-present tension between scientists and fossil hunters–who are, many times, everyday people whose interest in natural science compels them to find, restore and, often sell their discoveries for profit–drives much of the narrative of The Dinosaur Artist: Obsession, Betrayal, and the Quest for Earth’s Ultimate Trophy.

The ever-present tension between scientists and fossil hunters–who are, many times, everyday people whose interest in natural science compels them to find, restore and, often sell their discoveries for profit–drives much of the narrative of The Dinosaur Artist: Obsession, Betrayal, and the Quest for Earth’s Ultimate Trophy.

In her book, Williams reveals the real-life story of Eric Prokopi, a Florida fossil hunter/dealer who sold the skeleton of an 8-foot tall, 24-foot long Tyrannosaurus in the Big Apple for more than $1 million–and created an international “custody battle” for the specimen, triggered by the Mongolian government.

Williams’ love of journalism came alive while she was a student at Ole Miss and a former staff writer for the Clarion-Ledger and Jackson Daily News. She has blended her natural curiosity and love of writing to unearth unusual and unexpected stories around the globe–but she credits much of her love for writing to members of her family who were unusually good story tellers.

A National Magazine Award winner, Williams is the Laventhol/Newsday Visiting Professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism; and her journalistic work has appeared multiple times in volumes of The Best American Magazine Writing and The Best American Crime Writing.

Please tell me about growing up in Mississippi and how you discovered your interest in journalism.

Paige Williams

Happy to! I was born in Oxford, grew up in Tupelo, and graduated from Ole Miss, where I majored in journalism and minored in history. During college, I worked as a reporter and editor at The Daily Mississippian, the campus newspaper, and at the Tupelo Daily Journal and–hello!–the Clarion-Ledger/Jackson Daily News. Reporting and writing for the C-L/JDN, I learned priceless lessons from colleagues such as Alan Huffman, Mary Dixon, and Dewey English, and covered a range of news.

Where did the journalism spark originate? I’m not really sure. My mother is and was a devoted newspaper reader, and I grew up watching her read the paper. During college I came across “journalism” as a major in the course catalog and liked the sound of it. I knew zero journalists, but I signed up and loved it, particularly because one of my teachers was the amazing Tommy Miller, who’d been an editor at the Houston Chronicle.

But I equally credit the storytellers in my family–in Tupelo, Smithville, Ingomar, and the Delta–for a lifetime of filling my ear with the sound of their hilarious, absurd, heartbreaking stories. It’s also not a coincidence that I spent a lot of my childhood in the school library and the public library, which had a powerfully positive effect on me. I still remember the delicious smell of the Lee County Library.

At what point did you realize your own interest in writing and that this would be your career path?

Once I discovered journalism at Ole Miss, I couldn’t imagine doing anything else. I had no real concept of what life as a journalist might look like, or even how much it paid–it never occurred to me to ask.

I knew only that journalism would make for an interesting life and contribute to the world in some meaningful way. It also meant that I got to write for a living. The writing felt like a natural extension of the reading and storytelling background I just mentioned. I should add that I’m by no means the best storyteller in my family; I’ve got relatives who could keep you entertained for days.

An early boyfriend–a reporter I met while working in Jackson, as it happens–was the first to tell me, “You’re a writer!” The idea thrilled me, but I didn’t quite know what he meant, or what to make of it.

In journalism, I often felt confused by what others saw as a necessary division between reporting and writing, when really the two are intertwined. Editors seemed to think you had to be good at either one or the other. One editor told me, in a moment that she surely saw as supportive rather than destructive, “We know you like to dig, but just write–just write!” I wanted to marry the two, and to find a home at a place that supported the sort of immersive journalism that appealed to me.

Tell me about your interest in narrative journalism–that is, writing about real-life investigations you’ve uncovered.

A wide range of things interest me, but I’m often drawn to stories about wrongdoing, and about abuse of power and privilege involving flawed characters or problematic systems. One piece involved the problem of judicial override in Alabama–wherein, in capital cases, a judge can unilaterally sentence a criminal defendant to death, even when a jury unanimously votes for life.

I’m also interested in unexpected relationships, and so I enjoyed reporting and writing a piece about the brilliant self-taught Southern artist Thornton Dial and his charismatic patron. Another involved a onetime movie star’s decision to remove a vintage Tlingit totem pole from a ghost village in Alaska and erect it in his backyard in Beverly Hills–a story that was really about respect, or in this case, lack thereof, for other cultures.

Now that the book is done, I’m looking forward to getting back to a life devoted primarily to those kinds of stories.

How would you explain the world’s longtime obsession with dinosaurs among both children and adults?

The big ones were really big; the ferocious ones were really ferocious, and, other than birds, they’re all gone. The extinction of the terrestrial dinosaurs is almost unthinkable: these fascinating, diverse animals were wildly successful creatures for hundreds of millions of years–until they weren’t.

In The Dinosaur Artist, you make a very clear case for the reasons commercial dealers in dinosaur remains are at odds with paleontologists. Can you condense that debate, and tell us why you say paleontology became “perhaps the only discipline with a commercial aspect that simultaneously infuriates scientists and claims a legitimate role in the pantheon of discovery”?

The science of paleontology wouldn’t exist without non-scientist hunters–ordinary people who bother to notice fossils, which are all around us, and wonder what they are, and when and how the corresponding animals lived at one point on this planet.

The science is a relatively young one, but humankind’s questions about the natural world are ancient ones: why are shark teeth found on mountain tops? What force of nature could coil a stone? Natural history museums are filled with the finds of ordinary people who simply pursued their curiosity about the world around them–explained, of course, by the scientists who study fossils in order to understand the history of life on earth. Naturally, paleontologists want to preserve fossils, which are fundamental to their work; commercial hunters sell their finds, which a scientist would never do, and believe they’re salvaging materials that would otherwise weather away.

The tension over who should have the right to collect fossils, and whether fossils should ever be sold, divides the scientific and commercial communities to an extent that should be resolvable, considering that both sides love the same objects, whether dinosaur bones or fossil dragonflies or prehistoric flowers.

Your book is no doubt an introduction for most readers to the world of fossil hunting, collecting, and selling–through the real-life story of Eric Prokopi, a 38-year-old Florida man who had built a successful business in the trade. It would be the skeleton Prokopi brought to market in a 2012 Manhattan display–of a valuable T. bataar (closely akin to T. rex)–that would be his downfall. Although an auction for the specimen would bring more than $1 million, it was soon discovered that the fossil had been stolen from Mongolia, and Prokopi’s world began to unravel. How did you find out about this story, and why did you decide to write a book about it?

I had been thinking about a book on the fossil world, and dinosaur poaching, for years by the time the Prokopi case came along. The commercial aspect of fossils had come to my attention in the summer of 2009–in Tupelo, as it happens. I happened to be home, and was sitting in a coffee shop, reading the newspaper, when I saw a news brief about a convicted dinosaur thief in Montana, who was about to be sentenced to prison. I looked into his case, and while I lost interest in that particular situation, I kept learning about the larger fossil world, the rich history of natural history, and the tension between scientists and ordinary people who love nothing more than walking around and looking for bits of natural history to collect and study.

In early 2013, I wrote a story about the Prokopi case. When Prokopi was sentenced to prison, in 2014, it became clear that the story as it continued to unfold went far enough to support a book-length work. As the reporting continued, it became clear that forces beyond science and commerce were at work in this particular case. Those forces involved the fall of the Soviet Union, the unlikely rise of democracy in post-communist Mongolia, and the United States’s fascinating and increasingly important and strategic diplomatic relationship with Mongolia, which is landlocked between Russia and China. Crazily enough, that long history related to this dinosaur case.

The details and the depth of research for this book are amazing, as you expand the story into much further investigation of the fossil trade as a whole. What do ordinary people need to know about what’s happening with this relatively new business, and why is it important that we understand what’s going on?

Thank you! You may have noticed the 80-something pages of chapter notes. Those aren’t just reference materials; they’re mini-stories in themselves, and they’re the one place in the book where I allowed myself to use the first person rather than inserting myself into the main narrative.

None of this should feel daunting. At the heart of this story, which spans millennia and continents, are people. They’re collectors and gravediggers and plumbers and teachers and scientists who share an obsession with nature and natural history. As much as anything, it’s a book about the darker side of pursuing one’s passions, and, in Prokopi’s case, about catastrophic life choices that affected his finances, marriage, and freedom.

The Dinosaur Artist by Paige Williams is Lemuria’s December 2018 selection for its First Editions Club for Nonfiction. Signed copies are available in our online store.

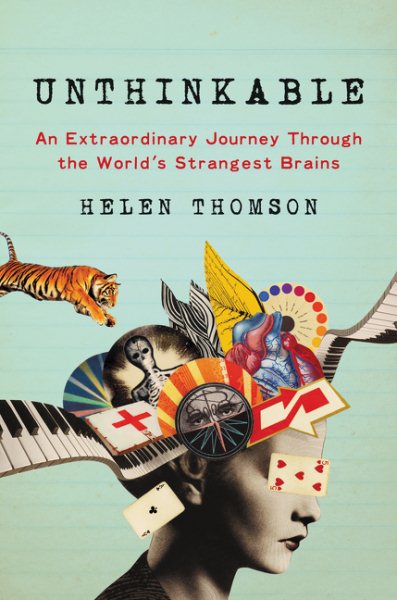

But when I looked at Unthinkable when we got them in, the cover just grabbed ahold of my attention. Each chapter focuses on a real person from around the world and the rare brain disorder they have. The chapter that made me buy this book is about a man named Graham who, for three years, believed he was dead. Objectively, he knew he wasn’t. He was able to walk and talk and tell the doctor he was “dead,” but for some reason, his brain wasn’t letting him grasp that he was alive.

But when I looked at Unthinkable when we got them in, the cover just grabbed ahold of my attention. Each chapter focuses on a real person from around the world and the rare brain disorder they have. The chapter that made me buy this book is about a man named Graham who, for three years, believed he was dead. Objectively, he knew he wasn’t. He was able to walk and talk and tell the doctor he was “dead,” but for some reason, his brain wasn’t letting him grasp that he was alive.

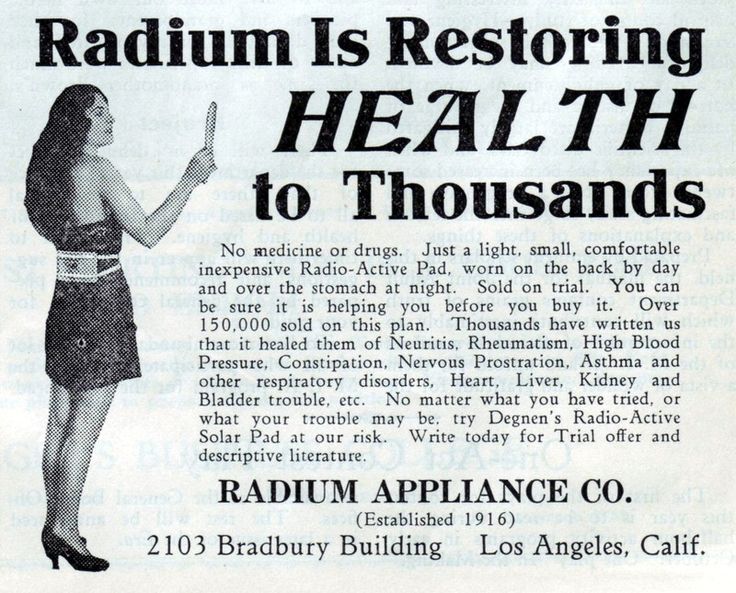

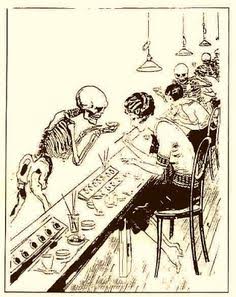

Most, if not all, of the girls who worked for USRC started getting ill. Some had sore mouths, some had achy joints, some started walking with limps, and some showed all of the symptoms. Several of the women developed deadly sarcomas. Since radium affected each girl differently, the sources of their illness were misdiagnosed. Syphilis, “phossy jaw,” early onset arthritis, etc. were some of the main diagnoses. These “radium girls” were dying left and right, and USRC kept denying that their deaths were work-related. Finally, with the help of sympathetic doctors and committee agents, radium was finally pinpointed as the cause of these deaths and illnesses.

Most, if not all, of the girls who worked for USRC started getting ill. Some had sore mouths, some had achy joints, some started walking with limps, and some showed all of the symptoms. Several of the women developed deadly sarcomas. Since radium affected each girl differently, the sources of their illness were misdiagnosed. Syphilis, “phossy jaw,” early onset arthritis, etc. were some of the main diagnoses. These “radium girls” were dying left and right, and USRC kept denying that their deaths were work-related. Finally, with the help of sympathetic doctors and committee agents, radium was finally pinpointed as the cause of these deaths and illnesses. So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed

So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed The Great Beanie Baby Bubble

The Great Beanie Baby Bubble Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans

Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of Elements

The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of Elements Dispatches from Pluto: Lost and Found in the Mississippi Delta

Dispatches from Pluto: Lost and Found in the Mississippi Delta

Can you believe that students will be starting college next month? At Millsaps College all incoming freshman are required to read one book. Professor Patrick Hopkins of Millsaps gives us an introduction to this year’s pick.

Can you believe that students will be starting college next month? At Millsaps College all incoming freshman are required to read one book. Professor Patrick Hopkins of Millsaps gives us an introduction to this year’s pick.

It was 1951. Rules and expectations for participants in medical research were just beginning to be debated and it would take years before the norm in research was that patients should be asked for permission to use their biological specimens for research. Would it surprise you to find out that even today, in 2013, a patient with cells as valuable as Lacks would be no more likely to share in profit from those cells than she? To find out that cells could be immortalized and patented and make millions of dollars but the patient receive nothing? To find out that patients entering research studies are explicitly told they won’t make any money from any commercial products their cells might result in?

It was 1951. Rules and expectations for participants in medical research were just beginning to be debated and it would take years before the norm in research was that patients should be asked for permission to use their biological specimens for research. Would it surprise you to find out that even today, in 2013, a patient with cells as valuable as Lacks would be no more likely to share in profit from those cells than she? To find out that cells could be immortalized and patented and make millions of dollars but the patient receive nothing? To find out that patients entering research studies are explicitly told they won’t make any money from any commercial products their cells might result in?