by Norris Rettiger

As a bookseller, there’s a lot of motivation to say that a book won’t hurt you. That it won’t make you uncomfortable or give you the sense that you’re running your eyes along something that was never meant for you.  But if I told you Ocean Vuong’s novel debut On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous wasn’t going to cut deep and draw blood, wasn’t going to push you away and make you cry, wasn’t going to get under your skin and find its way into your brain, then I wouldn’t be telling you the truth. There’s a moment in the book where Vuong’s stand-in character “Little Dog” has a conversation with his mother and comes to realize that they were “exchanging truths, which is to say… cutting each other.” If there’s room on your heart for another gash or two, this book has truths to exchange.

But if I told you Ocean Vuong’s novel debut On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous wasn’t going to cut deep and draw blood, wasn’t going to push you away and make you cry, wasn’t going to get under your skin and find its way into your brain, then I wouldn’t be telling you the truth. There’s a moment in the book where Vuong’s stand-in character “Little Dog” has a conversation with his mother and comes to realize that they were “exchanging truths, which is to say… cutting each other.” If there’s room on your heart for another gash or two, this book has truths to exchange.

Casting off the textbook “conflict-driven” narrative, Vuong’s words cascade over the story of a mother and a son and an immigrant family and the brief beauty of so many things that never get to stay beautiful. In equal parts, it is a loving portrait of men and women and a shockingly blunt attack on the culture they were forced to live in. The bottomless poetry of Vuong’s writing paired with such a soulful story will make you forget the word “plot” exists, drawing you completely into this new way of seeing, of breathing, of bleeding. But it won’t let you be comfortable, because this is a book written by and for young queer Vietnamese-Americans. Vuong is clear about that. And so there’s a constant contradiction that gives the book such elasticity and nuance—the words will immerse you completely, or, it will seem like they do, but really the book cannot help but hold us at arm’s length. Even though the idea of a book communicating something is deemed important by most literary critics, that’s not Vuong’s goal here.

The book is narrated as a letter, but it is not like most epistolary novels: the narrator, Little Dog, is writing to his mother, and she is illiterate. “The very impossibility of your reading this is all that makes my writing possible,” he says. For those of us who can read, and perhaps even do read very frequently, it can be hard to run into a book that so completely believes that we cannot understand it: that it isn’t for us. We say, “no, Vuong, you are wrong, this book is not just for young queer Vietnamese-Americans, that cannot be true, every book is for everyone.” But in that moment we display our ignorance of the fact that this still isn’t about us. Near to the end of the book, the narrator closes a paragraph with a heartbreaking line: “I am worried they will get us before they get us.”

It is not so much about communication as it is about the barriers to that communication. There is so much here in this book; so many specifics that are conveyed with the knowledge that they really can’t be truly understood. There’s a frustration with language and a reaching for the poetry that transcends, while also recognizing that transcendence is really just nothingness. And nowadays, nothingness is a dangerous void that fills rapidly with the ugliness and the divisive rhetoric that enslaves the minds of millions. Ocean Vuong leaves no voids, attempts no grandness, and leaves behind only the cipher of a life—symbols on a page in a book in a hand on the earth in this particular moment. And that’s not nothing. That’s something—and that’s the thing that matters the most.

And so, as a bookseller, I have a problem with communication, too. I can’t tell you how you’re going to react to this book, and I can’t even adequately and reasonably express my own experience with it. But that’s okay. Because it’s not always about communication. Sometimes things just need to be said, and sometimes it works out that the thing that’s said is heard by someone, and sometimes that thing gets heard in a way that makes it understood more than it was before. Maybe not by much, but maybe by a little, and that little bit finds itself remembered. And that remembering turns that understanding into a memory and memory might, someday, give us a second chance—Vuong writes obsessively about second chances. Because second chances are the opportunity to remember, to allow ourselves to learn.

And there is something in it for us, the people who this book “isn’t for.” There’s a reason to dive in and take the shock and pain with gritted teeth and open heart—because every second spent reading this book will be a chance for us to become more, to become more human, to become more “us.”

Signed first editions of On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous are currently available at Lemuria’s online store.

Hosseini’s newest book,

Hosseini’s newest book,  One of my all-time favorite books–French or not–is

One of my all-time favorite books–French or not–is  Two recent books that completely captured me were

Two recent books that completely captured me were  Bao Ninh features prominently in Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s series on the Vietnam War. Ninh is a Vietnamese writer and former North Vietnamese soldier. Ninh’s novel,

Bao Ninh features prominently in Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s series on the Vietnam War. Ninh is a Vietnamese writer and former North Vietnamese soldier. Ninh’s novel,  First published in Vietnam in a low-budget format by the Writers Association Publishing House of Hanoi in 1991, the book was translated into raw English by Phan Thanh Hao and rewritten by Australian war journalist and author Frank Palmos. At this point, the English translation was given the title “The Sorrow of War” and was published in Great Britain by Secker and Warburg in 1993 and in the United States by Pantheon in 1995.

First published in Vietnam in a low-budget format by the Writers Association Publishing House of Hanoi in 1991, the book was translated into raw English by Phan Thanh Hao and rewritten by Australian war journalist and author Frank Palmos. At this point, the English translation was given the title “The Sorrow of War” and was published in Great Britain by Secker and Warburg in 1993 and in the United States by Pantheon in 1995.

Now, at first glance, you may think that this is a heavy book and by “heavy,” I mean emotionally heavy. I won’t lie to you and say that isn’t in there, but amidst the rawness of Karl Ove’s descriptions there lies a certain beauty that is just as much frightening as it is entrancing. As Knausgaard begins to describe the world to his daughter, he engages in deep reflections on everything from cars to war, Flaubert to twilight, and bottles to beekeeping. What follows is a refreshing view of ordinary life as it is explained to one who has not yet experienced anything outside of a mother’s womb. In essays like “Lightning,” the author delves into the odd relationship between horror and beauty as he and his family watch a gigantic bolt of lightning hit the street outside their home. In “Flaubert,” the author reflects upon his favorite novel and the distinction between literary enjoyment and study. The heart of each meditation is the urge of the author to find what exactly it is that makes life worth living. As Knausgaard takes on each new topic, describing it as though it has never been seen, the reader is brought into the depths of the real and at times the philosophical. “Labia,” as an example, explores the complexity of male sexuality and the shame that often follows closely behind it. “Vomit” takes opportunity to explore the plethora of bodily fluids that we are all familiar with, but puts inquiry into the generally hatred that human beings have for that which is “usually yellowish” and still contains “chunks of pizza” and other remnants of the “undigested.”

Now, at first glance, you may think that this is a heavy book and by “heavy,” I mean emotionally heavy. I won’t lie to you and say that isn’t in there, but amidst the rawness of Karl Ove’s descriptions there lies a certain beauty that is just as much frightening as it is entrancing. As Knausgaard begins to describe the world to his daughter, he engages in deep reflections on everything from cars to war, Flaubert to twilight, and bottles to beekeeping. What follows is a refreshing view of ordinary life as it is explained to one who has not yet experienced anything outside of a mother’s womb. In essays like “Lightning,” the author delves into the odd relationship between horror and beauty as he and his family watch a gigantic bolt of lightning hit the street outside their home. In “Flaubert,” the author reflects upon his favorite novel and the distinction between literary enjoyment and study. The heart of each meditation is the urge of the author to find what exactly it is that makes life worth living. As Knausgaard takes on each new topic, describing it as though it has never been seen, the reader is brought into the depths of the real and at times the philosophical. “Labia,” as an example, explores the complexity of male sexuality and the shame that often follows closely behind it. “Vomit” takes opportunity to explore the plethora of bodily fluids that we are all familiar with, but puts inquiry into the generally hatred that human beings have for that which is “usually yellowish” and still contains “chunks of pizza” and other remnants of the “undigested.”  You might think that having magic hair that’s attuned to your emotions would be a blessing, but the titular character in

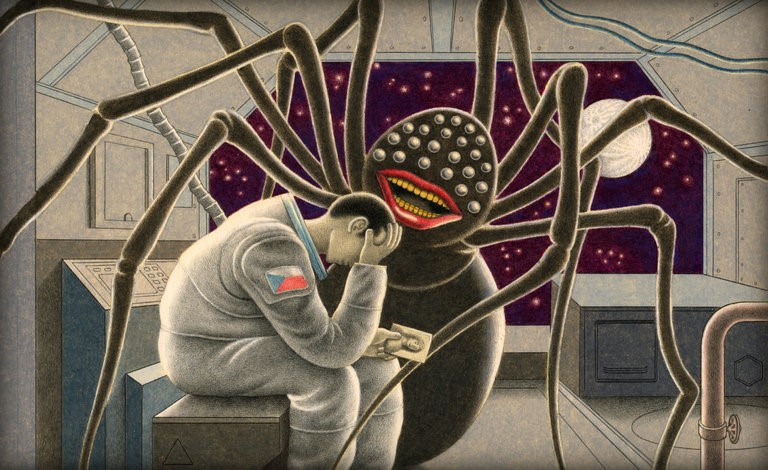

You might think that having magic hair that’s attuned to your emotions would be a blessing, but the titular character in  Jaroslav Kalfar’s

Jaroslav Kalfar’s

This is how the story of Nadia and Saeed begins, in a country teetering on the brink of a civil war. The dangerous country is never named, but it is obvious that it is somewhere in the Middle East. People are living here in constant fear, people are shot on their way to work, and sometimes even in their own homes.

This is how the story of Nadia and Saeed begins, in a country teetering on the brink of a civil war. The dangerous country is never named, but it is obvious that it is somewhere in the Middle East. People are living here in constant fear, people are shot on their way to work, and sometimes even in their own homes.