by Andrew Hedglin

(With sincerest apologies to Wallace Stevens)

I

The title character of Kim Church’s Byrd is Byrd, a boy born in North Carolina in 1989 who is given up for adoption by his mother, Addie Lockwood. He is almost a McGuffin, almost completely absent from the narrative, except that the story follows the lives of people important to him in his birth family, especially his birth mother Addie, and to a lesser extent, his birth father, Roland Rhodes. This book is a long shadow cast by the boy Byrd.

II

I stumbled across this book while receiving inventory for the store in the backroom. For technical reasons I won’t bore you with, I thought Byrd was a new release. It is not; it was published in 2014 by Dzanc Books (a small publisher), and only in paperback. Lemuria has only ever ordered two copies, three years late, and the only one it has ever sold (as of this writing) has been to me. This book is criminally underappreciated.

III

Besides Ron Rash telling me this was a good book in a blurb, I was sold on it by the first sentence of the summary on the back: “Addie Lockwood believes in books.” I know what that means. Addie shares my opinion, or perhaps I share hers, that The Brothers K by David James Duncan is an “Unheard-Of Masterpiece.” Addie seems a little bit more ambivalent about the process of bookselling than I am, but to each her own.

IV

A man and a woman

Are one.

A man and a woman and a blackbird

Are one.

V

I was almost overwhelmed by the beauty of this book. I had to put it down the first time, because I was reading something else and didn’t want to crowd it. First of all, it handles the old verities of hope, of loss, and of human folly with a deft, humanistic touch. Second, Church handles the use of time exceedingly well. The story covers a huge stretch of time, about forty-odd years of Addie’s life. Even though the progression is linear, it is still an accomplishment to make it feel so smooth. Church reminds of another female North Carolina writer, Anne Tyler, in this way.

VI

Look, what I’m about to share does not convey, exactly, the main thematic thrust of the book, but it’s my favorite passage because I’m kind of a romantic, and I’m always detained and delighted when I find a new way of thinking about love. Also, the passage is beautiful and poetic. Here it is:

Neither of them thinks of love the way they used to, as something to be fallen into, like a bed or a pit. It isn’t big or deep or abstract. Love is particulate. It’s fine. It accumulates like dust.

VII

Not one character is this book is wasted, or less than human. Not Addie, not Roland, not Addie’s mother Claree nor her father Bryce, not Addie’s astrologer Warren, not Roland’s wife Elle. I am convinced Church could have plucked any random background figure out of the book, made them fascinatingly human, and made their story cohere to the whole.

VIII

As a coincidence, this article from The Atlantic, written two years ago in response to Pope Francis’s remarks about declining Western birthrates and a then-newly published anthology about chosen childlessness, came up in my Facebook feed. Byrd, in this book, is an accident. His conception, yes, of course, but also his birth itself. Addie’s attitude about her decision, and her subsequent gnawing curiosity about the life she created, is one of the subtlest motifs in an already subtle book. Setting aside the raging inferno surrounding the abortion debate in our culture, the discussion of a birth in our society is only easy when everything goes right and everyone is wanted, shunting miscarriage, infertility, chosen childlessness, and sometimes adoption into a silence that I am grateful that fiction can sometimes have the ability to fill.

IX

And speaking of accidents, I can’t help but thinking about the book I previously talked about in this space, Careless People (a bibliographical biography of The Great Gatsby). It refers to a forgotten meaning of the word accident: “Catholic theologians used the word ‘accidental’ to describe the inessential bread and wine left behind after the ritual of communion had turn them into mystical symbols…accidentals [are] the inessential objects that once glittered…disenchanted things made ordinary again….the accidental is all that we are left with once we have lost our illusions.” This is what Byrd, or the knowledge of Byrd, is for Addie after she loses her illusions about Roland.

X

Not that I guess this has much to do with anything, but would it surprise you to know that Church, the author, used to be a high-powered lawyer? That choice speaks to an ambition exceeded by anybody in this novel, including Addie. That Church chose to write this book instead of a legal thriller is to me (who enjoys a good legal thriller now and again) a minor miracle.

XI

Byrd does have an interesting surrogate in this novel, his half-brother Dusty. His existence doesn’t seem to answer any questions about Addie, but it does offer a lot of insight about Roland, and in general people’s capacities to change or to love. So I guess it does tell about Addie, in a suggestive rather than definitive way. That this is the way the whole book operates might drive some people crazy, but it’s part of why I love it so.

XII

Addie’s greatest secret, besides withholding Byrd’s existence from Roland the second time, is that her affair with Roland in the first place. Not that she had an affair, not that it produced a child, not that she gave her child up, but because it was with Roland, whom she supposed she should be over. This book could be a coming-of-age novel, but it lasts so long in Addie’s life that it is also an age-passing-by novel. It is not only about the making of a person, but the consideration, evaluation, and self-doubt about who that person becomes.

XIII

Almost the very last words of the book are Addie’s “I have hopes but no expectations.” I hope I haven’t spoiled the book by telling you that, but what I really worry is that I’ve spoiled the book by telling you any of this. I have certainly implanted some sort of expectation in you, the reader, if you’ve read this far, if you’ve decided to give the book a chance. Expectations of not only the plot, which I believe are overrated, but of this book’s quality. With this handicap, I don’t think you can enjoy the total surprise Byrd was for me, but even a shadow of the surprise is still astonishing, I assure you.

China Miéville’s October is an electrifying centenary tour through Russia’s axial 1917. Acting as expert guide, he whisks readers through the labyrinthine history of that land, past Tzars and Rasputin, to focus on the intimate details of factory-level debates, cabinet meetings, bureaus, letters, trains, revolutions, and the Revolution. Most of us have a sense of where this particular drama ends or at least what came later, but Miéville throws the reader into scene after scene of this spectacular story.

China Miéville’s October is an electrifying centenary tour through Russia’s axial 1917. Acting as expert guide, he whisks readers through the labyrinthine history of that land, past Tzars and Rasputin, to focus on the intimate details of factory-level debates, cabinet meetings, bureaus, letters, trains, revolutions, and the Revolution. Most of us have a sense of where this particular drama ends or at least what came later, but Miéville throws the reader into scene after scene of this spectacular story.

The Confusion of Languages

The Confusion of Languages Jaroslav Kalfar’s

Jaroslav Kalfar’s

The first book on my list is the new novel from Alissa Nutting,

The first book on my list is the new novel from Alissa Nutting,  Her only option is to seek refuge in her father’s home that is in a retirement trailer park. Did I mention that her widower father has just purchased a brand new lifelike sex doll named Diane? Hazel’s father’s hope is that in his last years he will die doing something that he loves; obviously, that thing is having sex with Diane. “Hazel began to look at the five-foot four-inch silicone princess a little differently now: Penthouse pet from waist up, Dr. Kevorkian from the waste down.” If this little bit I’ve just shared does not convince you to buy this book, then we do not share the same sick sense of humor…and that is totally your choice. Albeit the wrong one, but I digress.

Her only option is to seek refuge in her father’s home that is in a retirement trailer park. Did I mention that her widower father has just purchased a brand new lifelike sex doll named Diane? Hazel’s father’s hope is that in his last years he will die doing something that he loves; obviously, that thing is having sex with Diane. “Hazel began to look at the five-foot four-inch silicone princess a little differently now: Penthouse pet from waist up, Dr. Kevorkian from the waste down.” If this little bit I’ve just shared does not convince you to buy this book, then we do not share the same sick sense of humor…and that is totally your choice. Albeit the wrong one, but I digress. Number two is

Number two is  Watch Me Disappear

Watch Me Disappear Number four is

Number four is  Last but not least is number five on the list,

Last but not least is number five on the list,  White’s debut novel is about a man who, as a teenager, went to a gay-to-straight conversion camp in Mississippi. When the story of the camp is made into a movie, the main character, Will Dillard, returns to his roots and finally reckons with his past. The story is told through memories and reads almost like a memoir, as it focuses on emotions and is told primarily through internal dialogue. But the plot–the truth of what really happened that summer–kept me turning pages.

White’s debut novel is about a man who, as a teenager, went to a gay-to-straight conversion camp in Mississippi. When the story of the camp is made into a movie, the main character, Will Dillard, returns to his roots and finally reckons with his past. The story is told through memories and reads almost like a memoir, as it focuses on emotions and is told primarily through internal dialogue. But the plot–the truth of what really happened that summer–kept me turning pages. In

In  To those who have heard his name, Arthur C. Clarke is most well-known as the co-creator of the book and subsequent film 2001: A Space Odyssey. However, his influence does not stop at cinema. Clarke’s theories in his books about satellites and orbits actually came to fruition in reality, so much so that a geosynchronous orbit used by telecommunications satellites is named after him (

To those who have heard his name, Arthur C. Clarke is most well-known as the co-creator of the book and subsequent film 2001: A Space Odyssey. However, his influence does not stop at cinema. Clarke’s theories in his books about satellites and orbits actually came to fruition in reality, so much so that a geosynchronous orbit used by telecommunications satellites is named after him ( There has been a lot of debate as to which author is truly the quintessential sci-fiauthor, and nearly every one comes to the same conclusion. Philip K. Dick made massive contributions to the entire genre of Science-Fiction, molding it into what it is today. Many of PKD’s works have been adapted to film and television, though few know it. Total Recall, The Adjustment Bureau, Minority Report, The Man in the High Castle, and Blade Runner are all based on his works. Because of this, many people are more familiar with his stories than they realize. My favorite work of his is Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, which was the basis for the film Blade Runner. It is a detective story at it’s heart, the story of Rick Deckard, a “Blade Runner,” a detective who specializes in identifying and decommissioning rogue androids. It’s an interesting take on the classic mystery novel, and I love it.

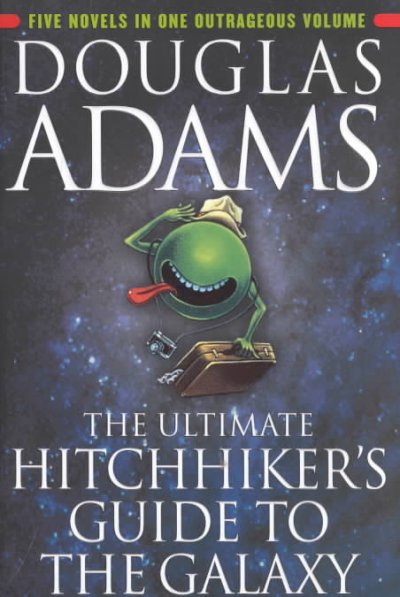

There has been a lot of debate as to which author is truly the quintessential sci-fiauthor, and nearly every one comes to the same conclusion. Philip K. Dick made massive contributions to the entire genre of Science-Fiction, molding it into what it is today. Many of PKD’s works have been adapted to film and television, though few know it. Total Recall, The Adjustment Bureau, Minority Report, The Man in the High Castle, and Blade Runner are all based on his works. Because of this, many people are more familiar with his stories than they realize. My favorite work of his is Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, which was the basis for the film Blade Runner. It is a detective story at it’s heart, the story of Rick Deckard, a “Blade Runner,” a detective who specializes in identifying and decommissioning rogue androids. It’s an interesting take on the classic mystery novel, and I love it. Douglas Adams was, for the most part, a humorist in the vein of Mark Twain, but his genre of choice was science fiction. His masterpiece, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and its sequels, now published together as The Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, are the best example of his sharp wit and absurdist style of Adams’ work. The opening of the book features (spoiler alert, although it is the beginning of the book) the destruction of Earth, after which Adams writes “This planet has—or rather had—a problem, which was this: most of the people living on it were unhappy for pretty much all of the time. Many solutions were suggested for this problem, but most of these were largely concerned with the movement of small green pieces of paper, which was odd because on the whole, it wasn’t the small green pieces of paper that were unhappy.” The book is likely the one that I have reread the most, and in my mind, it is, not only one of the funniest novels, but one of the best ever written at all.

Douglas Adams was, for the most part, a humorist in the vein of Mark Twain, but his genre of choice was science fiction. His masterpiece, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and its sequels, now published together as The Ultimate Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, are the best example of his sharp wit and absurdist style of Adams’ work. The opening of the book features (spoiler alert, although it is the beginning of the book) the destruction of Earth, after which Adams writes “This planet has—or rather had—a problem, which was this: most of the people living on it were unhappy for pretty much all of the time. Many solutions were suggested for this problem, but most of these were largely concerned with the movement of small green pieces of paper, which was odd because on the whole, it wasn’t the small green pieces of paper that were unhappy.” The book is likely the one that I have reread the most, and in my mind, it is, not only one of the funniest novels, but one of the best ever written at all. Sarah Churchwell’s

Sarah Churchwell’s  Fortunately, I was reacquainted with Gatsby & Co. almost a decade later when it was I, as an English teacher, who assigned Gatsby to a new crop of high school sophomores. I had a better appreciation by then of American history, and dreams, and ambition, and poetry—and so, too, the novel itself. But mine was a fairly by-the-numbers enlightenment about the books’ genius.

Fortunately, I was reacquainted with Gatsby & Co. almost a decade later when it was I, as an English teacher, who assigned Gatsby to a new crop of high school sophomores. I had a better appreciation by then of American history, and dreams, and ambition, and poetry—and so, too, the novel itself. But mine was a fairly by-the-numbers enlightenment about the books’ genius.