First, read this article.

Now, read this.

To most of us, college is a time to broaden horizons, mentally stretch, and to find out where to draw our lines. For Tara Shultz, the line was immovable from the beginning with no hope of being re-drawn. The problem of her protest is twofold: trying to force the books out of curriculum for all students instead of personally removing herself from the class is ultimately a selfish and bullying tactic; and by claiming that she was “expecting batman and robin, not pornography” is patronizing and belittles an entire genre of literature (and its authors) that can have the emotional depth and breadth of the written novel.

We at Lemuria have been striving to carve room in the store to build up our stock of graphic novels that we believe are fulfilling, fun, and thought-provoking. We encourage all of our readers, young and old, to explore this medium of literature and remain open-minded as they read. Ultimately, a graphic novel on any subject can be challenging because instead of being the commander of your imagination and creating your own version of the world being described to you, an illustrator takes that power away from the reader. It can be hard to un-clench our fists and relinquish that control. However, handing over the power of imagination to the artist does not make this mode of literature any less powerful or interactive. I believe that reading a graphic novel is in no way a passive act like watching television, but that it works different muscles in your brain, much like switching from jogging to swimming; both are cardio, both are effective exercises, but you can get sore in different places.

We at Lemuria have been striving to carve room in the store to build up our stock of graphic novels that we believe are fulfilling, fun, and thought-provoking. We encourage all of our readers, young and old, to explore this medium of literature and remain open-minded as they read. Ultimately, a graphic novel on any subject can be challenging because instead of being the commander of your imagination and creating your own version of the world being described to you, an illustrator takes that power away from the reader. It can be hard to un-clench our fists and relinquish that control. However, handing over the power of imagination to the artist does not make this mode of literature any less powerful or interactive. I believe that reading a graphic novel is in no way a passive act like watching television, but that it works different muscles in your brain, much like switching from jogging to swimming; both are cardio, both are effective exercises, but you can get sore in different places.

On several occasions when reading a graphic novel that was particularly weighty in its subject matter, having the wheel of imagination taken out of my hands was a relief. I can’t speak for all readers, but being able to take my mind off of the architecture of the world in the story and focus my attention on the characters themselves- it was transformative. So many brilliant artists use the illustrations in a graphic novel like a highlighter, underlining important ideas or phrases. In David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp, as the protagonist ages and changes, so does the style of art on the pages; and, peeling back even more layers of the title character, the style evolves even more as his opinions of the people around him change. It’s like looking through a pair of binoculars into a microscope; ultimately tricky and hard to wrap your mind around at times, but as the images come sharply into focus, the headache goes away and the wonder begins.

On several occasions when reading a graphic novel that was particularly weighty in its subject matter, having the wheel of imagination taken out of my hands was a relief. I can’t speak for all readers, but being able to take my mind off of the architecture of the world in the story and focus my attention on the characters themselves- it was transformative. So many brilliant artists use the illustrations in a graphic novel like a highlighter, underlining important ideas or phrases. In David Mazzucchelli’s Asterios Polyp, as the protagonist ages and changes, so does the style of art on the pages; and, peeling back even more layers of the title character, the style evolves even more as his opinions of the people around him change. It’s like looking through a pair of binoculars into a microscope; ultimately tricky and hard to wrap your mind around at times, but as the images come sharply into focus, the headache goes away and the wonder begins.

In a turn of events that would probably surprise one miss Tara Schultz, the first time I experienced the moment when the rug of low expectations was pulled from beneath me was- you guessed it- when I picked up Batman: The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller. Poetic justice is a glittering and sharp sword. Miller weaves a story of regret and a scabby old identity crisis instead of simple vigilante justice and a good old fashioned political spanking for the corrupt. The Bruce Wayne of Miller’s Gotham City is older, tireder, and angrier than we are used to, and his self-conscious antics are equally compelling and embarrassing to see. The feeling of intense, growling reality that came from watching a man transform in such raw and painful way was shocking. I went in expecting witty one-liners and came out at the end shocked and emotional; feeling as if I had had a cold bucket of water sloshed over my head.

In a turn of events that would probably surprise one miss Tara Schultz, the first time I experienced the moment when the rug of low expectations was pulled from beneath me was- you guessed it- when I picked up Batman: The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller. Poetic justice is a glittering and sharp sword. Miller weaves a story of regret and a scabby old identity crisis instead of simple vigilante justice and a good old fashioned political spanking for the corrupt. The Bruce Wayne of Miller’s Gotham City is older, tireder, and angrier than we are used to, and his self-conscious antics are equally compelling and embarrassing to see. The feeling of intense, growling reality that came from watching a man transform in such raw and painful way was shocking. I went in expecting witty one-liners and came out at the end shocked and emotional; feeling as if I had had a cold bucket of water sloshed over my head.

This new age of literature isn’t so new- Miller’s Dark Knight was released in 1986- but it feels as if it’s just had a fresh bath. More literary readers are turning to the medium for consumption, and authors are skillfully doing away with the “Batman and Robin” stereotype that people like Tara Shultz are trying to paste over the whole genre. Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home waltzed into the spotlight when it was rewritten for the stage and recently won a Tony for Best Musical. Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi (one of the books that Shultz is protesting) became so widely known and influential that it has become required reading for many high school social studies classes. We are lucky enough to be living in a time where art, literature, and music are being appreciated and consumed in ways we never could have foreseen, but that won’t stop naysayers from trying to do away with anything they deem inappropriate or different. Educate yourselves. Read new things, stretch those unused muscles, and help us to encourage the growth of a generation of forward-thinking, open minded individuals.

This new age of literature isn’t so new- Miller’s Dark Knight was released in 1986- but it feels as if it’s just had a fresh bath. More literary readers are turning to the medium for consumption, and authors are skillfully doing away with the “Batman and Robin” stereotype that people like Tara Shultz are trying to paste over the whole genre. Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home waltzed into the spotlight when it was rewritten for the stage and recently won a Tony for Best Musical. Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi (one of the books that Shultz is protesting) became so widely known and influential that it has become required reading for many high school social studies classes. We are lucky enough to be living in a time where art, literature, and music are being appreciated and consumed in ways we never could have foreseen, but that won’t stop naysayers from trying to do away with anything they deem inappropriate or different. Educate yourselves. Read new things, stretch those unused muscles, and help us to encourage the growth of a generation of forward-thinking, open minded individuals.

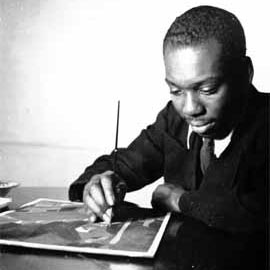

Jacob Lawrence was not your typical painter. He often spent months at a branch of the New York Public Library, taking notes from journals and books and other documents before he would began work on a formal painting project. Lawrence wanted his art to teach history to his people. In describing his research efforts for The Great Migration, Lawrence remarked:

Jacob Lawrence was not your typical painter. He often spent months at a branch of the New York Public Library, taking notes from journals and books and other documents before he would began work on a formal painting project. Lawrence wanted his art to teach history to his people. In describing his research efforts for The Great Migration, Lawrence remarked: