by Andrew Hedglin

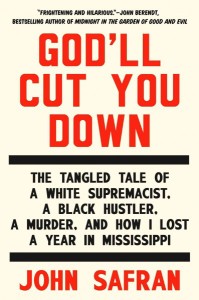

A 67 year-old white supremacist is violently killed in his home by a 22 year-old black man, who then mutilates his corpse. How’s that for a précis?

Two things (besides John Berendt’s blurb on the front cover) made me want to read John Safran’s God’ll Cut You Down one day when I came across checking our inventory:

Two things (besides John Berendt’s blurb on the front cover) made me want to read John Safran’s God’ll Cut You Down one day when I came across checking our inventory:

1) Whoever titled this book is a genius. Although originally titled Murder in Mississippi in Safran’s native Australia, there’s a lot of mileage you can get out of the words to this old folk song, famously and recently recorded by Johnny Cash. First the pounding bass line gets stuck in your head immediately, like a song for a kick-ass mental movie trailer. It also sets up a certain set of expectations. Which brings me to the second enticement…

2) I first heard about the ballad of Richard Barrett around the dinner table by family members who have long been plugged into the Jackson scene. Anecdotes of the can-you-believe-this? variety. And the final act was one to beat all.

Now in my house, the barest facts told the story: the 22 year-old black man, Vincent McGee, was tired of oppression and white supremacy. At the very least, Barrett had finally reaped all the hate he had sown of his forty-year career of racist lunacy. McGee was an instrument of divine justice; God had cut Richard Barrett down.

John Safran, the Jewish-Australian host of gotcha-television shows and a self-described “Race Trekkie,” had played a prank on Barrett the year before his death for his show. A year later and across the world, he saw people on the internet make the same assumption, but other people make add vague complications as motivations (sex and money), and found the picture to be incomplete. This is no classic whodunit—it’s a tangled why-dun-it. And that proves to be more complicated than the writer or reader might anticipate.

So Safran read a bunch of true-crime novels, like In Cold Blood and Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, and studied the form. There’s supposed to be a paradigm about how you see the world: I’ve told how I think things happened, but as Safran learned in Mississippi, two people can see the exact same thing and have two different explanations as to how and why it happened (and about things less fantastic than a race murder).

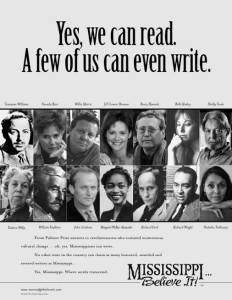

Research complete, Safran hops on a plane to Jackson to investigate. One of the most charming things about Safran is his ability to recognize his own shortcomings. The first scene in Mississippi where he encounters this poster in the airport as he ruminates on his lack of experience as a writer is hilarious and amazing.

Research complete, Safran hops on a plane to Jackson to investigate. One of the most charming things about Safran is his ability to recognize his own shortcomings. The first scene in Mississippi where he encounters this poster in the airport as he ruminates on his lack of experience as a writer is hilarious and amazing.

I should admit though that he does bite back later in the book when passing by the poster on his way into town again. And that’s one of the things I found most fascinating about the book as a Mississippian; books where the outsider comes in and tries to make sense of what’s going on read like poetry, when the familiar becomes strange. It breaks you out of the prison of your own experience.

Safran interacts with varying degrees of public figures: Barrett, Jackson Advocate reporter Earnest McBride, white supremacist podcaster Jim Giles, state representative John L. Moore, Madison and Rankin County DA Michael Guest, and even a cameo by a pre-mayoral Chokwe Lumumba. Just as interesting are his interviews with McGee’s family and his paramours, and Barrett’s neighbors and his former associates. Safran doesn’t use kid gloves in his treatment, but he’s not out to make a buffoon out of anybody, either—despite what reservations his television stunts might inspire.

As Safran digs deeper into the night of the murder, and the lives of both Barrett and McGee that led them there, he becomes less sure about it all. Race casts a long shadow over everything, as does religion, mental illness, and repressed sexuality. The only thing he seems to uncover for sure is the complicated humanity of both men. William Faulkner never said “To understand the world, you must first understand a place like Mississippi”; but you know, in my opinion at least, Mississippi’s as good a place as any to start. And you will first learn about the stupid truth, always resisting simplicity.

I hope you find this new swing in pop culture as exciting as I do. Come celebrate this nerd pride with us tonight at 5:00 in our .dot.com building and meet Ernest Cline himself. We’ll be the ones in the corner selling copies of Armada, Ready Player One, awesome merch, and quoting The Breakfast Club or arguing with you about the over use of the eagles in The Lord of the Rings. We would love to nerd out with you.

I hope you find this new swing in pop culture as exciting as I do. Come celebrate this nerd pride with us tonight at 5:00 in our .dot.com building and meet Ernest Cline himself. We’ll be the ones in the corner selling copies of Armada, Ready Player One, awesome merch, and quoting The Breakfast Club or arguing with you about the over use of the eagles in The Lord of the Rings. We would love to nerd out with you.

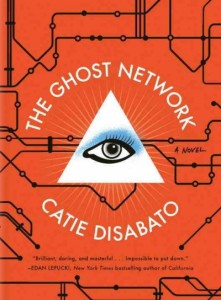

Throughout the investigation, Disabato clues the reader into the activities of a secret society, their motives and methods, and weaves real world history, geography, and pop culture into their intrigue. I almost feel sorry for anyone that picks this book up after 2015, because it is meant for a right now audience. The missing diva is clearly a stand in for our world’s Lady Gaga, but with a side of conspiracy, and the characters looking for her could be any number of her devoted fans, served with heaping helpings of free time, an extra order of natural detective ability, and an insatiable appetite for pop.

Throughout the investigation, Disabato clues the reader into the activities of a secret society, their motives and methods, and weaves real world history, geography, and pop culture into their intrigue. I almost feel sorry for anyone that picks this book up after 2015, because it is meant for a right now audience. The missing diva is clearly a stand in for our world’s Lady Gaga, but with a side of conspiracy, and the characters looking for her could be any number of her devoted fans, served with heaping helpings of free time, an extra order of natural detective ability, and an insatiable appetite for pop.