Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (November 25)

Frank LaRue Owen’s interest in poetry began to develop in his teens, and his journey to become a poet in his own right has developed alongside his spiritual growth, through years of thoughtful studies of Asian spiritual practice.

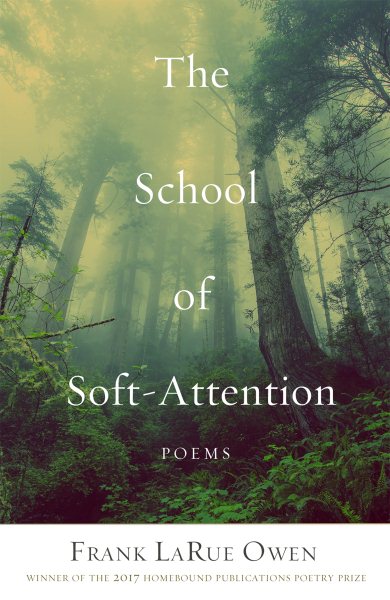

His first book of poetry, The School of Soft-Attention, was named the winner of the Homebound Publications Poetry Prize in 2017.

His first book of poetry, The School of Soft-Attention, was named the winner of the Homebound Publications Poetry Prize in 2017.

The book puts into words Owen’s reflections on key influences on his life, including the Ch’an/Daoist hermit-poetic tradition, Zen meditation, eco-psychology, and a practice he calls “pure land dreaming.” Shaped by Owen’s diversity of cultural experiences and the depth of his spiritual training, his poems encourage readers to “turn to a new way of seeing, a new way of paying attention to the life within and around us.”

A strategist with a metro area marketing-creative firm, Owen has also completed a second book of poetry, The Temple of Warm Harmony, set to release in fall 2019.

Please tell me about your background and how your many opportunities to experience a variety of cultures in many places has helped shape your life today.

I hail from a family with long-standing roots in Mississippi and East Texas. We’ve been educators, ministers, counselors, attorneys, oilmen, cowboys, poets, and artists.

I spent my formative years in Atlanta and Jackson, with my last year of high school spent in Chapel Hill, N.C., where I was introduced to writing through a creative writing class. That high school teacher sent me to a writer’s conference at University of North Carolina at Winston-Salem. I’ve been writing, in one form or another, ever since.

My moving around so much is largely due to my academic journey and my cultural and spiritual explorations. I spent three years in northern Wisconsin at a small environmental college called Northland College where I had an opportunity to study Asian religions, anthropology, psychology, writing, as well as environmental studies at the Sigurd Olson Environmental Institute, named for Sigurd Olson, who lived from 1899 to 1982, and was a renowned author, wilderness defender, and teacher.

I attended graduate school at Naropa University in Boulder, Colo., North America’s first accredited Buddhist university, which houses not only a graduate school in mindfulness-based counseling psychology, which I graduated from, but also the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, also known as the MFA in Writing and Poetics, founded by the late Allen Ginsberg, Anne Waldman, and other poets of note, including one of my poetic mentors, the late Jack Collom.

The School of Soft-Attention, your debut book of poetry, was named the 2017 winner of the Homebound Publications Poetry Prize. Did this honor surprise you?

It was a total surprise to win. Poetry had always been more of a personal exploration, an extension of spiritual practice, and not something I sought to formally publish. I created and maintained some online poetry blogs starting around 2000, but never thought it would lead to actual publishing. In 2016, with a lot of encouragement from various quarters, I gathered up what I considered my best work and entered it in the Homebound Publications Poetry Prize for review.

I still consider myself a ‘work-in-progress’ as a poet, so it was unexpected. But it has resulted in a wonderful publishing relationship with Homebound, which is continuing beyond The School of Soft-Attention.

Which came first–the discovery of your talent for writing poetry, or your serious interest in Eastern philosophies?

I dabbled in poetry as an art form in my teen years, and even read some of the poems of Japan’s greatest poets at that time. But I never really developed it. My involvement with Asian spiritual practice really came first, initially through my study of the Japanese martial art of Aikido starting in 1989, and then study of Zen meditation shortly after. I studied Chinese and Japanese religions academically in my undergraduate years with Thomas Kasulis, a scholar of Asian religions, but quickly realized my interest was that of practitioner and not limited to the academic.

Tell me about your journey with doña Río: who was she, and what did she teach you about life, spirituality, and, ultimately, poetry?

Her name was Darion Gracen, a psychologist, wilderness guide, and practitioner-teacher of Ch’an, or Zen, meditation. She was known by many names, “doña Río” among them, and she served as a mentor to many. Initially, I met Darion in an academic setting, but eventually I studied with her in other contexts. She would host circles of people in the mountains of Colorado where we studied an array of subjects with her rooted in meditative awareness in the natural world. Later, after she moved to the Santa Fe, New Mexico, area, I continued studying with her one-on-one for another decade. She embodied a kind of “curriculum” that combined silent illumination, or meditation from the Ch’an or Zen tradition, the practice of dreamwork, a spiritual approach to experiences in the natural world, and poetics as way to process experiences with all of the above.

Ultimately, what I learned from her was how to make one’s heart-mind an ally, how to attend to the creative process, and how one’s essential connection to the Dao, or, the sacred, transcends conditions.

You dedicate this book to Río and to your parents. Please tell me about your parents and their influence on the direction of your life and poetry.

Although rooted in the social justice tradition of United Methodism, my parents have always been very supportive of my journey of cultural investigation and spiritual inquiry, even if this took me into traditions other than their own.

In large part, I attribute to my parents my curiosity about life, my creativity, my love of nature and history, my ability to ascertain value in the world’s cultures and wisdom traditions, and my open mind. Each in their own way has been shaped by Jungian thought and a love of nature. My father continues to study Jungian psychology and the work of a Jungian named James Hollis. My mother–an artist herself–also taught me from a very young age to consult the Chinese I Ching, or “Book of Changes,” and to pay close attention to dreams as a source of life guidance and wisdom, which dovetailed nicely with my studies later in life.

Explain the term soft-attention, and its meaning in your poetry.

There is a dynamic contrast between urban modernity, with its high-velocity pace and incessant barrage of information and bad news that assaults the senses, and the natural world, which has a slower rhythm and a healing power that restores balance in a person, body and mind. The latter isn’t just a quaint idea. As clearly demonstrated in a book titled Forest Bathing by Dr. Qing Li, it is verified by vast studies by medical science.

As I say in one of my poems, it’s possible to “get too much of the world on you.” When this happens, we may find our consciousness becoming harsh, hardened, disfigured. Too much time lived in such a state is detrimental to our health, both physically and psychologically. So, the turn of phrase, “the school of soft-attention,” is a poetic way of referring to the natural world, what we call “the realm of mountains, forests, and rivers” in Daoist and Zen traditions. Time spent in this “school” invites, invokes, instills a very different quality of consciousness, one characterized by a “soft-attention.” From my point of view as a poet, poetry is about observation and perception. For me, the craft of writing poetry has become inseparable from this “soft-attention.” I essentially can’t write unless I’ve entered that level of awareness.

What do you mean when you describe yourself as a hermit-poet?

In a nutshell, it’s a solitary leaning. I require a lot of solitude, for spiritual practice, artistic practice, landscape practice. From the point of view of Buddhist practice, there are various accepted ways or paths e.g. monastic, lay-householder, etc. Though they may have had earlier training in a community context, hermits go their own way and walk a solitary path in this regard. It was the same with my teacher.

The hermit-poet is something of an archetype in the contemplative and literary traditions of China and Japan. A hermit-poet is someone who has placed contemplative practice and artistic life at the center of their existence. When most Westerners hear the word “hermit” they automatically think “recluse” or “misanthrope.” The terms are not synonymous in the Asian contemplative or literary traditions. A recluse is one who leaves the world behind, never to return. Not so with hermits in Daoist and Zen tradition, who remain in contact with society. In fact, there is an old saying from China that goes ‘the small hermit lives in the mountains; the great or accomplished hermit lives down in the town.’

Many of your poems in this book speak of the ordinary–the everyday things of life. In what ways can readers apply some of the lessons of your poetry to their own lives?

My poetry is not for everyone. There are large swaths of people in modern life–“modernistas,” my late teacher would say–who are content with their compartmentalized life, and with the distractions mainstream culture feeds them. They go to a job; they chase money, perceived social status, wealth, or fame; they go home at the end of the day and spend their nights in a TV-saturated trance.

My poetry deals with other points of focus. The mystery of dreams. The inner life. The non-obvious qualities of the places where we live. Though there are letters strung together into lines, and those lines form what appear to be “poems” on the page, I’m not certain if what I write constitutes poetry. They are snapshots of moments from the flow of existence that issue an invitation to the reader–to ponder the true nature of their life, the life of the soul.

In the end, I would be gratified if one or two of the poems stirred people to be a bit more awake to the passage of their life and to ask a few deeper questions about what matters most.

What role does music play in your life and in your writing?

Alongside time in nature, music is a key part of my life and poetry. Music figures heavily in my creative process of writing and other art-making. Likewise, when I publish poems on my website, purelandpoetry.com, each poem is presented with a specific image and soundscape, usually from the archives of ambient musicians to whom I’m connected like Forrest Fang, Roy Mattson, Steve Roach, or Byron Metcalf. Sometimes their music feels like an extension of a poem. Sometimes a poem feels like an extension of their music.

Tell me about your next book coming up.

The next book, being released in fall 2019 is entitled The Temple of Warm Harmony. In some sense, it is a continuation of the thread or emphasis of The School of Soft-Attention. However, I do take up some new themes and orientations. The Temple of Warm Harmony is divided into three sections: The World of Red Dust, Heartbreak and Armoring, and Entering the Temple of Warm Harmony.

We are living in tumultuous times, culturally, socially, and environmentally. The concept of “the world of red dust” comes from a very ancient Chinese Daoist and Ch’an, or Zen, poetic understanding of a world that has fallen out of balance. The poems in the next collection explore some of these aspects of imbalance, disharmony, and realignment with what is known in the traditions as The Way.

Frank LaRue Owen will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, November 28, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and read from The School of Soft-Attention.

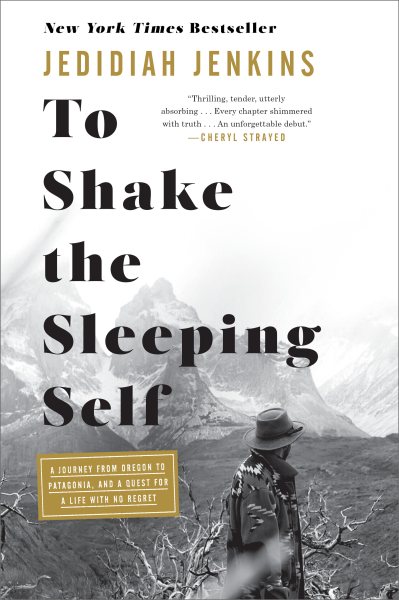

Like most millennials making connections in 2018, I found Jedidiah Jenkins through social media. As the editor of Wilderness magazine, Jedidiah filled his Instagram with lots of traveling and goofing around with his lovable squad. In fact, it was this account through which he first shared one of the biggest adventures of his life, gaining him coverage by National Geographic and eventually a book deal.

Like most millennials making connections in 2018, I found Jedidiah Jenkins through social media. As the editor of Wilderness magazine, Jedidiah filled his Instagram with lots of traveling and goofing around with his lovable squad. In fact, it was this account through which he first shared one of the biggest adventures of his life, gaining him coverage by National Geographic and eventually a book deal.

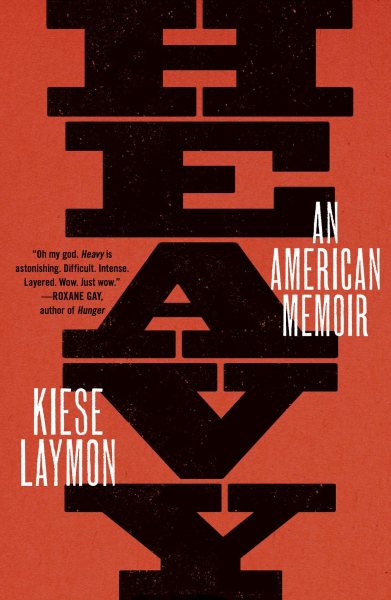

His new book, Heavy: An American Memoir (Scribner) is, literally, a long letter written directly to his mother, as he works through the complexity of his disordered childhood and its continued effects on his life today. The result is a deeply personal, and open, cry for answers as to why theirs was such a difficult relationship even as she unfailingly reassured him of her love.

His new book, Heavy: An American Memoir (Scribner) is, literally, a long letter written directly to his mother, as he works through the complexity of his disordered childhood and its continued effects on his life today. The result is a deeply personal, and open, cry for answers as to why theirs was such a difficult relationship even as she unfailingly reassured him of her love.

His first book of poetry,

His first book of poetry,  Monument

Monument

In fact, Isbell’s monumental work is a response to Katrina and the resiliency of our coastal institutions and residents. As a Pulitzer-Prize winning photographer, he chronicled the destruction of the hurricane for The Sun Herald, the Gulfport/Biloxi-based daily newspaper. Isbell explains in his introduction to the The Mississippi Gulf Coast that the work has “special meaning, as it was a therapeutic endeavor after the destruction from Hurricane Katrina.”

In fact, Isbell’s monumental work is a response to Katrina and the resiliency of our coastal institutions and residents. As a Pulitzer-Prize winning photographer, he chronicled the destruction of the hurricane for The Sun Herald, the Gulfport/Biloxi-based daily newspaper. Isbell explains in his introduction to the The Mississippi Gulf Coast that the work has “special meaning, as it was a therapeutic endeavor after the destruction from Hurricane Katrina.” Oxfords’s Glennray Tutor–who has been cited as not only one of the world’s top hyperrealist artists, but also one of the three who actually began the movement–shares his visionary style developed over more than three decades in his debut album,

Oxfords’s Glennray Tutor–who has been cited as not only one of the world’s top hyperrealist artists, but also one of the three who actually began the movement–shares his visionary style developed over more than three decades in his debut album,

From 1920 until 1933, Prohibition was the federal law of the land, banning alcohol across the country. But in Memphis, Prohibition lasted under state laws from 1909 until 1939. On page after page, author Patrick O’Daniel shows that Prohibition “led to increased crime, corruption, health problems and disrespect for all laws for three decades.”

From 1920 until 1933, Prohibition was the federal law of the land, banning alcohol across the country. But in Memphis, Prohibition lasted under state laws from 1909 until 1939. On page after page, author Patrick O’Daniel shows that Prohibition “led to increased crime, corruption, health problems and disrespect for all laws for three decades.” The award-winning novelist’s portrayal of a good-natured man whose hopes and dreams are literally forgotten when his memory is wiped out after “his Pontiac flies off a bridge into the icy depths of Lake Superior” is at once contemplative and relatable.

The award-winning novelist’s portrayal of a good-natured man whose hopes and dreams are literally forgotten when his memory is wiped out after “his Pontiac flies off a bridge into the icy depths of Lake Superior” is at once contemplative and relatable.

Key has returned with a metatextual sequel called

Key has returned with a metatextual sequel called  On the 20th anniversary of The Poisonwood Bible, Barbara Kingsolver gives us a timely novel in

On the 20th anniversary of The Poisonwood Bible, Barbara Kingsolver gives us a timely novel in