Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (March 24)

Among those worthy of celebrity status in mid-19th century America were rugged gunslingers whose reputations were often built on myths and legends borne of truth and tragedy–and one who reached the heights of notoriety was Wild Bill Hickock.

New York Times bestselling author Tom Clavin adds to his collection of historical nonfiction with Wild Bill: The True Story of the American Frontier’s First Gunfighter, examining in detail the life and rowdy times of this iconic American figure.

New York Times bestselling author Tom Clavin adds to his collection of historical nonfiction with Wild Bill: The True Story of the American Frontier’s First Gunfighter, examining in detail the life and rowdy times of this iconic American figure.

Notoriety gained from the press made Hickock a nationally known figure, and thus, placed a target on his back for hotshots who wanted to make a name for themselves as the man who would take him down.

A quick-draw artist who was known for his accuracy and courage when it came to gunfights, Hickock became a lawman at 20, and wen ton to hold the titles of Army scout, federal marshal, and Union spy. It would be a bullet that would end his life at age 39.

Clavin has served as a newspaper and web editor, magazine writer, TV/radio commentator and reporter for the New York Times. Among his career credits are awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation, an dthe National Newspaper Association. His book include Dodge City, The Heart of Everything That Is, and Valley Forge. Clavin lives in Sag Harbor, New York.

“Wild Bill” Hickock, hom you describe as the “first post-Civil War celebrity of the West,” was well-known as America’s first gunfighter during the 1800s–but his real name wasn’t even Bill. Tell us how James Butler Hickock became popularly known as “Bill”–and how he earned the legendary title of “Wild.”

Tom Clavin

Two separate events resulted in “Wild Bill.” The first and less dramatic is he had a brother who called himself Bill–his real name was Lorenzo–and probably as a joke when traveling together on a steamship on the Missouri River they called each other Bill. Lorenzo disembarked, “Jim” Hickock pushed on, and passengers called him Bill, and he got comfortable about this.

The “Wild” part happened after he entered a saloon fight on the side of a bartender outnumbered 6-to-1, and onlookers thought that was a wildly gutsy thing to do. From 1861 on, he was Wild Bill Hickock.

Why do say in your Author’s Note that it was a “gullible and impressionable public” that made Wild Bill bigger than all of the legendary frontier figures (like Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, and Kit Carson) who came before him?

There had always been a hunger back East for tall tales about frontier figures, bu the public became especially ravenous after the Civil War when the American frontier exploded with seemingly limitless potential. Hickock cut a romantic, larger-than-life figure and had a distinctive look and there was a bigger than ever number of readers. All this combined to almost overnight elevating him to superstar status.

It was a Harper’s New Monthly Magazine article in February 1867 that first spread Hickock’s name and legend across the nation, making him nationally famous at age 29. What effect did that article have on Hickock’s life?

The article made him very famous. He could not have been prepared for that, but he sort of took his fame in stride. Hickock did not seek attention, but he didn’t hide from it, either. He was mostly a modest man, but a part of him enjoyed being almost a mythical figure. The downside was much of his fame was as a best-in-the-West gunfighter, making him a target for those younger and possibly faster who wanted to take that title. For the rest of his life, he had to wonder which bullet had his name on it.

Briefly, for what exploits was Wild Bill best known?

Though we don’t have a lot of details, his years as a spy behind Confederate lines were full of exciting exploits. Obviously, being a gunfighter who could shoot faster and more accurately than any man he encountered. And especially when marshal of Abilene in Kansas, Hickock became the prototype of the two-fisted and two-gun frontier lawman. And he was the most well-known of Western plainsmen.

“Wild Bill,” was described as “the handsome, chivalrous, yet cold-eyed killer who roamed the prairie, a kind friend to children and a quick-drawing punisher of evildoers.” He died at age 39, and you liken his life to a Shakespearean tragedy. Explain how that comparison fits.

Hickock fits into that tragic mold dating from Euripides in Ancient Greece and elevated by Shakespeare of the hero who attained heights, but flaws felled him. The West changed fast around Wild Bill Hickock, and he was unable to adapt–and he was a gunfighter going blind.

Like many tragic heroes in literature, he sensed his days were short and life had been unfair but he courageously accepted what was to come. Hickock was an honorable man ultimately dealt a bad hand.

Tom Clavin will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, March 27, at 5:00 to sign copies of and discuss Wild Bill. Lemuria has chosen Wild Bill as its April 2019 selection for its First Editions Club for Nonfiction.

Famous for integrating the University of Mississippi in 1962, Meredith has been a challenging and criticizing voice in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi ever since. In some ways, Meredith started it all in his home state, and he documented that struggle in his first book

Famous for integrating the University of Mississippi in 1962, Meredith has been a challenging and criticizing voice in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi ever since. In some ways, Meredith started it all in his home state, and he documented that struggle in his first book  Rayne and Delilah’s Midnite Matinee

Rayne and Delilah’s Midnite Matinee

Award-winning, bestselling author Peter Heller reinforces his standing among America’s notable adventure writers with his riveting newest edition,

Award-winning, bestselling author Peter Heller reinforces his standing among America’s notable adventure writers with his riveting newest edition,

So I absolutely have to tell you about another book that you are going to love:

So I absolutely have to tell you about another book that you are going to love:  His newest,

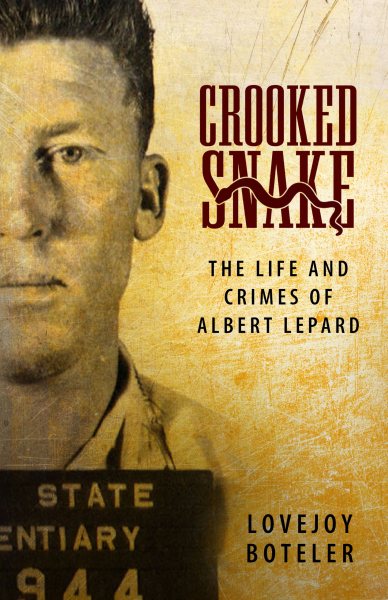

His newest,  “I don’t know how many people were kidnapped in Mississippi in 1968, but I was one of them,” writes author Lovejoy Boteler in the first sentence of the

“I don’t know how many people were kidnapped in Mississippi in 1968, but I was one of them,” writes author Lovejoy Boteler in the first sentence of the  Louisiana native and journalist Ken Wells fondly recalls what he and his five brothers called “the gumbo life” in rural Bayou Black–a lifestyle lived close to the land and that meant he would not see the inside of a supermarket until he was nearly a teenager.

Louisiana native and journalist Ken Wells fondly recalls what he and his five brothers called “the gumbo life” in rural Bayou Black–a lifestyle lived close to the land and that meant he would not see the inside of a supermarket until he was nearly a teenager.

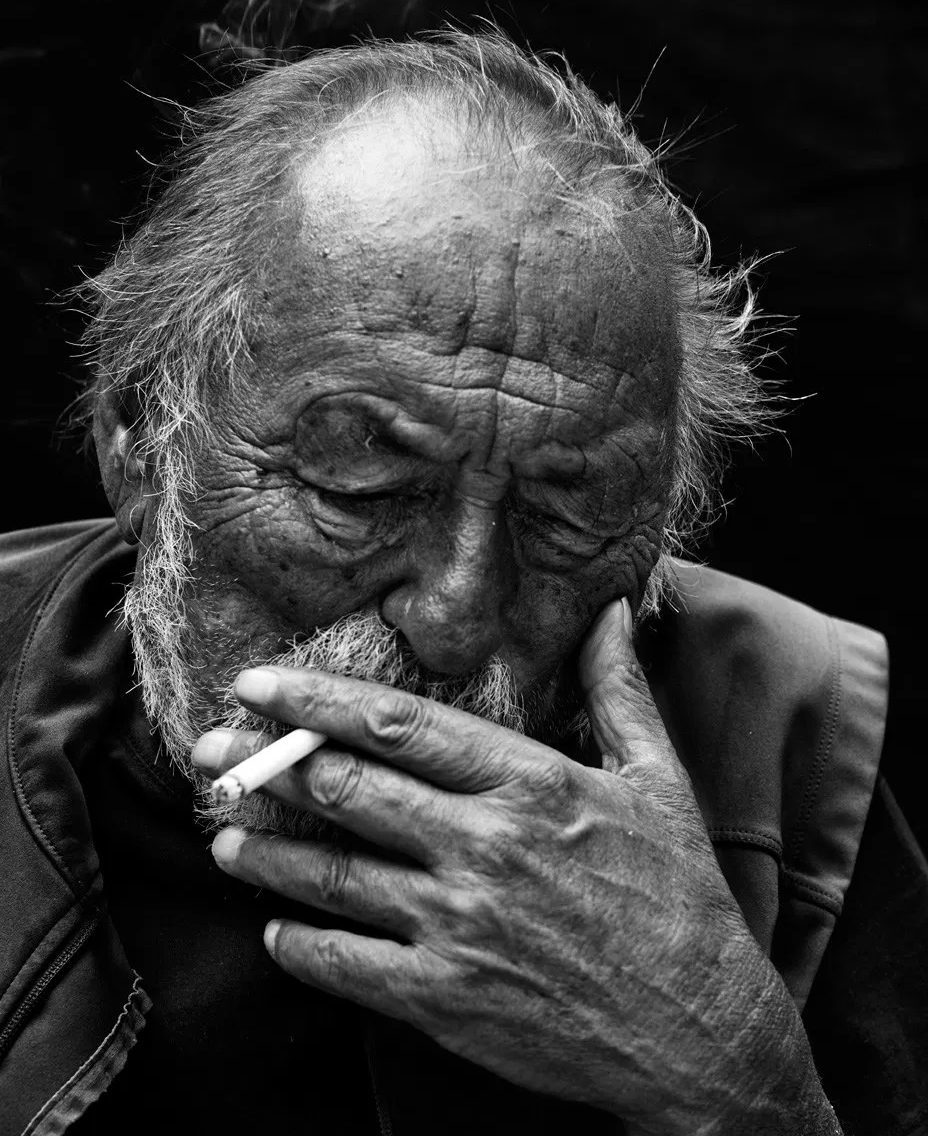

Jim Harrison knew he was dying when he wrote the poems in Dead Man’s Float. The grace with which he accepts his very end is comforting, but not all of the poems are about his life’s sunset. In another imitating-animals move, the poem “Mad Dog,” Harrison tells us that he “envied the dog lying in the yard,” so he lies down with it, rolling around, unable to find the same level of blissful comfort that his canine counterpart does. We’ve all been here: trying to make ourselves happy but blocked by ourselves. It’s funny, tongue in cheek, light.

Jim Harrison knew he was dying when he wrote the poems in Dead Man’s Float. The grace with which he accepts his very end is comforting, but not all of the poems are about his life’s sunset. In another imitating-animals move, the poem “Mad Dog,” Harrison tells us that he “envied the dog lying in the yard,” so he lies down with it, rolling around, unable to find the same level of blissful comfort that his canine counterpart does. We’ve all been here: trying to make ourselves happy but blocked by ourselves. It’s funny, tongue in cheek, light.