By Jim Ewing. Special to the Clarion Ledger Sunday print edition (March 17)

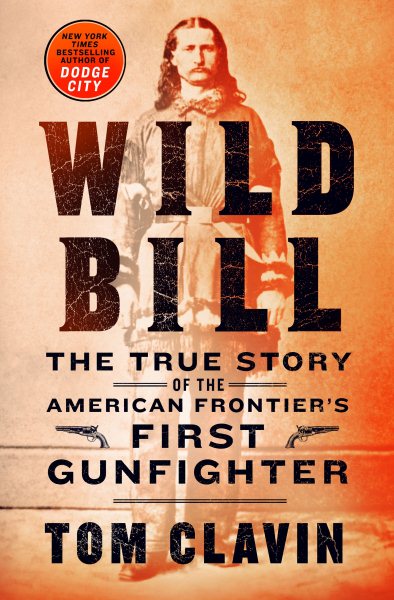

For those not especially knowledgeable about tales of the old frontier (other than movies and TV shows), Tom Clavin’s Wild Bill is full of surprises.

For those not especially knowledgeable about tales of the old frontier (other than movies and TV shows), Tom Clavin’s Wild Bill is full of surprises.

The first surprise in the book subtitled “The True Story of the American Frontier’s First Gunfighter” is that that Wild Bill Hickok’s name wasn’t Bill.

It’s believed that the man born as James Butler Hickok often joked with his brother Lorenzo by calling each other Bill. Since he answered to it, the name stuck. It may be also that James was known as the Wild Bill and his brother was the Tame Bill.

He signed all documents J.B. Hickok throughout his life.

Whether true or apocryphal, there’s no dispute that Wild Bill was an incredible marksman. Ambidextrous, he early on carried Colt Navy .36-cal. pistols facing butt out on each hip, which he later exchanged for double-action Colt .44s filed down for quicker action. He shot with both hands simultaneously and equally accurately.

“Witnesses report seeing Hickok driving a cork through the neck of a whiskey bottle at 20 paces, splitting a bullet on the edge of dime at the same distance, and putting as many as a dozen bullet holes in a tomato can that had been tossed in the air,” Clavin reports.

This skill made him a formidable foe in a gun battle and it also tended to dissuade lawbreakers when he served as marshal for the town of Abilene, Kansas, frequently putting on shows to demonstrate his prowess.

He also didn’t quite fit his “wild” moniker in his bearing and manner, in that he was by all accounts a cool customer. Raised in an abolitionist family in Illinois, during the Civil War, he served as a Union scout and spy, often going behind Confederate lines, and was able to coolly talk his way out of some tight binds. It was this ability to talk his way out of trouble, backed by his reputation as a crack shot, that later served him well as a lawman.

Much of what is known of Hickok through movies and Wild West shows is also probably fabricated, Clavin reveals. For example, it’s doubtful, he says, that Hickok and Calamity Jane were lovers. While they were friends, contemporary accounts seem to indicate that the somewhat dandy-ish Hickok who wore expensive clothes and bathed every day (an unheard-of practice at the time), considered her rather uncouth. She was prone to drunkenness and a prostitute who also wrangled horses, mules and cattle, usually wore men’s clothes, and was not known for her hygiene.

He also was devoted to his wife, Agnes, whom he married rather late in life (about the time he knew Jane), and she was flamboyant in a different way, as the owner of a circus and a world-renowned performer.

Calamity Jane claimed she and Hickok were lovers and had herself buried next to him at Deadwood, S.D., where he was shot dead from behind while playing what came to be called the dead man’s hand in poker: two pair, aces and eights.

What is known, according to Clavin, was that Hickok was the first fast-draw gunslinger in the Old West. His killing of a man in Springfield, Missouri, (Clavin says Independence, Missouri) July 21, 1865, by quick draw methods—rather than pacing off a duel—was widely reported and was quickly emulated across the West.

Unfortunately, because it also happened while he was quite young, it caused “shootists” who came along after to seek him out to show who was the fastest draw. He died at 39, Aug. 2, 1876, victim of a self-styled gunslinger who crept up on him.

But if a bushwhacker didn’t get him, the times would have. Hickok set the mold for gunman/lawmen who faced off in high noon style, but when he was killed, towns were shifting to “peace officers,” who arrested lawbreakers to take them before a judge, Clavin notes.

Hickok remained true to himself “while the West changed around him.”

Wild Bill is filled with the famous names of the West, such as Buffalo Bill Cody, Kit Carson, and the rest. It is a fascinating account of an incredible Western icon, diligently researched, and breath-taking in its scope.

Jim Ewing, a former writer and editor at the Clarion Ledger, is the author of seven books including his latest, Redefining Manhood: A Guide for Men and Those Who Love Them.

Tom Clavin will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, March 27, at 5:00 to sign copies of and discuss Wild Bill. Lemuria has chosen Wild Bill as its April 2019 selection for its First Editions Club for Nonfiction.

Comments are closed.