For those that don’t know, I’m the new guy at Lemuria, and I like new things. Books, movies, food, whatever it is, I like trying new things. Not that there is anything wrong with “old” things. I actually like a lot of those, too. This isn’t a post arguing the virtue of the exciting and shiny versus the tried and true. It is, however, a post about how revisiting something old has helped me to see something new.

If I’m being honest, moving back to Jackson a few months ago was not my favorite idea. As much fun as I had here in college, I had planned to spend my 20’s avoiding roots and any obligations. I thought I’d travel and move around, chasing jobs and adventures, making new friends, and trying as many new things as I could before it was time to be responsible and “settle down.” Things have not gone according to that plan. As I packed up to leave a “new” place and head towards this “old” one, I was reintroduced to this strange little book: Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. I don’t think it was coincidence that one of my new friends put it back into my hands just a short time before my move.

If I’m being honest, moving back to Jackson a few months ago was not my favorite idea. As much fun as I had here in college, I had planned to spend my 20’s avoiding roots and any obligations. I thought I’d travel and move around, chasing jobs and adventures, making new friends, and trying as many new things as I could before it was time to be responsible and “settle down.” Things have not gone according to that plan. As I packed up to leave a “new” place and head towards this “old” one, I was reintroduced to this strange little book: Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. I don’t think it was coincidence that one of my new friends put it back into my hands just a short time before my move.

Invisible Cities is a book without much of a story, and without many characters; but what it lacks in narrative, it makes up for in imagery. Kublai Khan has summoned Marco Polo to tell of the many great cities he has encountered throughout the Khan’s ever-expanding empire. The majority of the book is divided into chapters, each being Polo’s description of a city he has visited. Conversations between Khan and Polo are spread between these chapters. Across the barriers of language, age, culture, and experience, the two begin to communicate, Polo describing what he has seen with objects collected in his travels.

With no real plotline, Calvino’s writing focuses on the cross section of expectation and imagination, the fine line between understanding and knowing. Kublai Khan expects to hear of the towns and people spread throughout his empire, instead Marco Polo teases the emperor’s imagination, as well as the reader’s. Some of the places he claims to have visited are beautiful, others terrifying. Some are built up like modern cities with skyscrapers; others are built to defy common sense. They are all unique and richly detailed.

Through their conversation, Khan has some understanding of the cities Polo describes, yet never having visited, he can never know them as Marco Polo does. The reader is faced with a similar dilemma. We read the words Polo uses to name and depict all the places he has been, but the cities remain invisible to us, only truly existing in the explorer’s mind.

SPOILER ALERT…Sorta.

Of course, these cities aren’t real in our world, or in Khan’s empire. Each location described by Polo is a poem written in an urban language, one without words and phrases, but sometimes of concrete and steel, sometimes of stone, water, pipes, and more. The Explorer’s descriptions turn an idea into a landscape, one that he uses to impress the Emperor. Eventually Kublai Khan catches on to Marco Polo’s scheme and it is revealed that he has never traveled the empire, nor does he have any knowledge of any great cities other than his own Venice. All that he has described, all the ideas and fantastic depictions are inspired by his hometown. With every look at the Venice he loves, Polo sees an entirely new city.

It’s this thought that stood out to me as I read Invisible Cities again. Picturing the metropolises of Polo’s imagination while I read, I became jealous of his perspective that made each look at his “old” city seem like something “new.” This time, I was not reading about someone’s explorations and discoveries, I was reading about someone rediscovering a place already known. This made me change my mind about a few things and, as I’ve seen over the last few months, opened my mind to the new city I found in Jackson. It isn’t the same one I left, not in my mind. As Polo describes one of his cities, he says “You leave Tamara without having discovered it.” It seems I left Jackson without having really discovered it and now that I’m back, I have another chance.

Written by Matt

A story told through three different viewpoints,

A story told through three different viewpoints,  One escape I have thoroughly enjoyed recently is Vladimir Nabokov’s

One escape I have thoroughly enjoyed recently is Vladimir Nabokov’s  Imagine you’re broke (if you aren’t already), and you’ve just shown up to your successful cousin’s wedding. You’re without a gift, but even worse, you’re without a date. Old relatives are walking by and pinching your cheek asking when they’ll be able to come to your wedding.

Imagine you’re broke (if you aren’t already), and you’ve just shown up to your successful cousin’s wedding. You’re without a gift, but even worse, you’re without a date. Old relatives are walking by and pinching your cheek asking when they’ll be able to come to your wedding.

For the first time in a while, certainly all year, I am unsure of what to make of a book.

For the first time in a while, certainly all year, I am unsure of what to make of a book. This year was a doozy. I consumed everything from nonfiction about

This year was a doozy. I consumed everything from nonfiction about

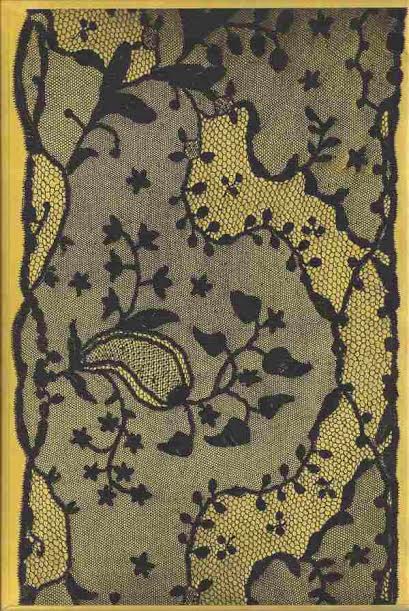

At the time “Love in the Time of Cholera” was published in the United States in 1988, García Márquez could not tour in the United States because of the government travel ban, so Random House mailed the sheets to García Márquez for him to sign. The sheets were bound into a beautiful limited edition of 350 copies with pink cloth over black cloth boards with a black lace patterned acetate jacket, housed in a yellow slipcase with a black lace pattern.

At the time “Love in the Time of Cholera” was published in the United States in 1988, García Márquez could not tour in the United States because of the government travel ban, so Random House mailed the sheets to García Márquez for him to sign. The sheets were bound into a beautiful limited edition of 350 copies with pink cloth over black cloth boards with a black lace patterned acetate jacket, housed in a yellow slipcase with a black lace pattern.

Haruki Murakami released

Haruki Murakami released