by Andrew Hedglin

One of the dual passions of my life has been reading books and following football. I have may have written about football a time or two on the blog before. I don’t know how large the Venn diagram cross section between the two segments are, but I have somehow landed firmly in the middle of them. And there have been a number of excellent football books that have come out this fall. If you happen to have somebody in your life who is both an unrepentant football fanatic and voracious reader, this is your guide to them all.

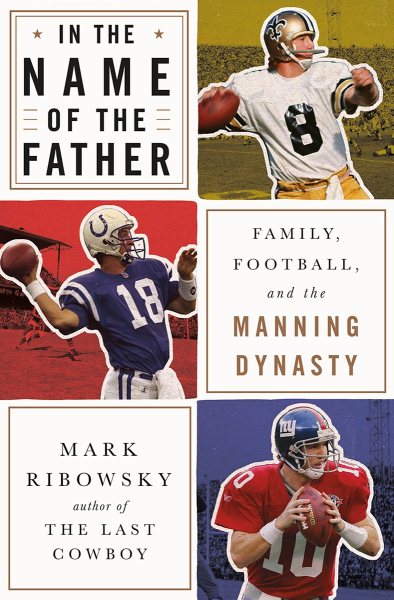

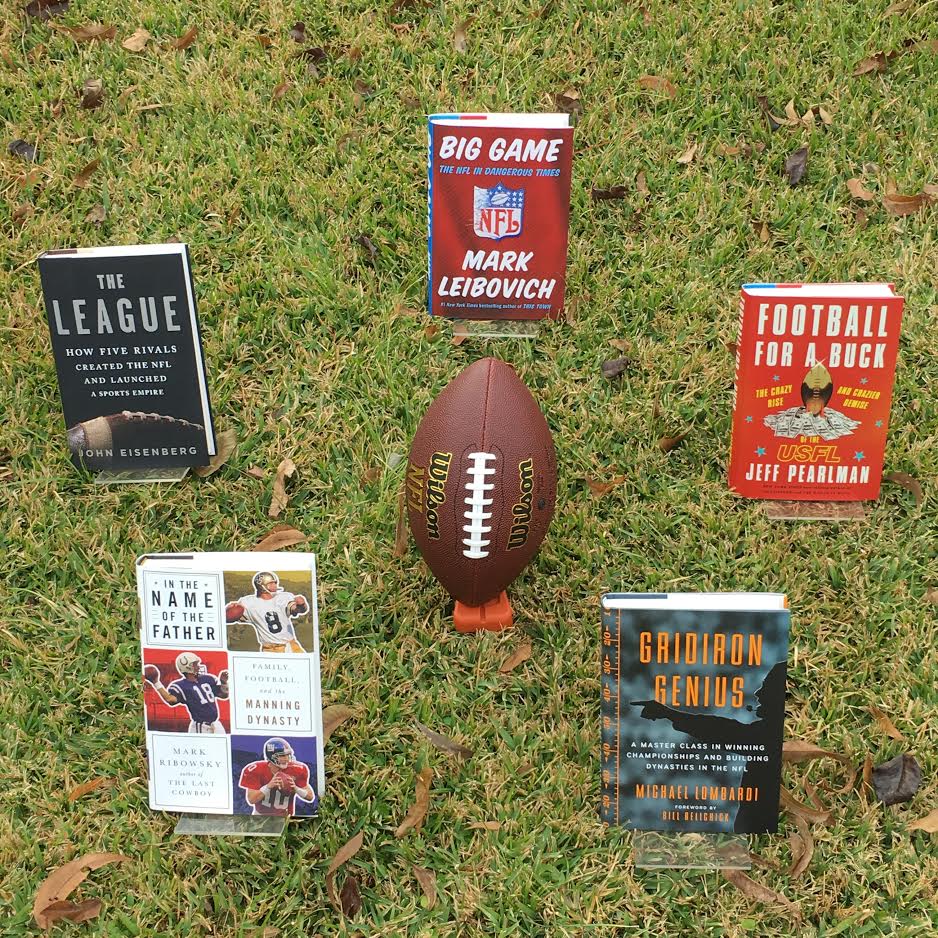

Part of the reason I became a football fan was because I loved watching Deuce McAllister run wild for the Ole Miss Rebels in the late 1990s. When he was drafted by the New Orleans Saints, that sealed my fate as being fans of those two teams. My dad had a similar experience with another player who followed that path before: the great Archie Manning. Mark Ribowsky, a professional biographer of musicians and sports figures, has come out with a new Manning chronicle, called In the Name of the Father: Family, Football, and the Manning Dynasty.

Part of the reason I became a football fan was because I loved watching Deuce McAllister run wild for the Ole Miss Rebels in the late 1990s. When he was drafted by the New Orleans Saints, that sealed my fate as being fans of those two teams. My dad had a similar experience with another player who followed that path before: the great Archie Manning. Mark Ribowsky, a professional biographer of musicians and sports figures, has come out with a new Manning chronicle, called In the Name of the Father: Family, Football, and the Manning Dynasty.

I was a little hesitant at first, because I had already read The Mannings by Lars Anderson last year, but In the Name of the Father is a little less hagiographic and focuses more on the pro careers of Archie, Peyton, and Eli, but I thoroughly enjoyed the fair but full portraits of Mississippi’s first family of football.

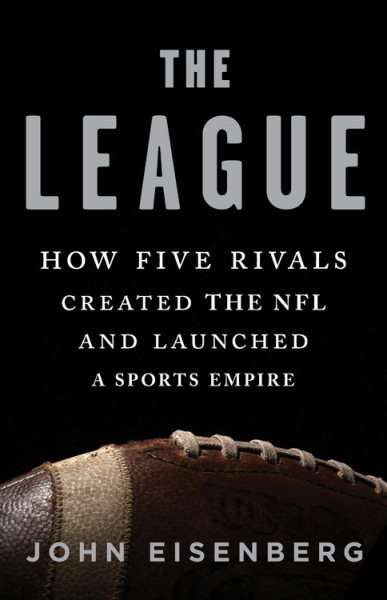

Another very fine history is John Eisenburg’s The League: How Five Rivals Created the NFL and Launched a Sports Empire. This may even be my favorite of these football books. The five rivals referred to in the title are George Halas of the Chicago Bears, Tim Mara of the New York Giants, George Preston Marshall of the Washington Redskins, Bert Bell of the Philadelphia Eagles, and Art Rooney of the Pittsburgh Steelers.

Another very fine history is John Eisenburg’s The League: How Five Rivals Created the NFL and Launched a Sports Empire. This may even be my favorite of these football books. The five rivals referred to in the title are George Halas of the Chicago Bears, Tim Mara of the New York Giants, George Preston Marshall of the Washington Redskins, Bert Bell of the Philadelphia Eagles, and Art Rooney of the Pittsburgh Steelers.

This is the most cohesive retelling of the NFL’ s origins that I’ve ever read, and I was as engrossed by owner’s “for the good of all” ethic as I was thrilled by references to the NFL’s history like the Hupmobile dealership, the Galloping Ghost, the Sneakers Game, the Steagles, 73-0, Slingin’ Sammy Baugh, and the Greatest Game Ever Played.

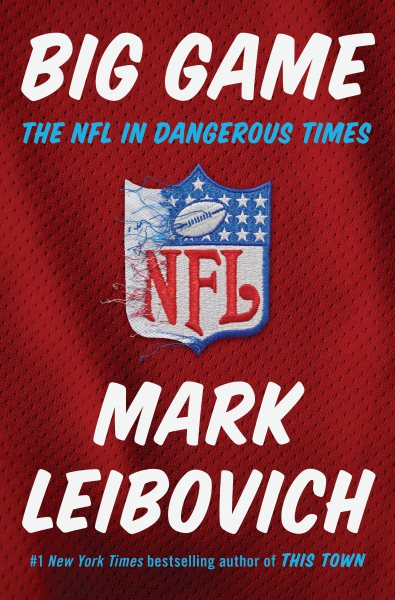

A somewhat disheartening but occasionally hilarious follow-up to The League would be Mark Leibovich’s exposé Big Game: The NFL in Dangerous Times. Leibovich is, by trade, a political reporter famous for his Washington insiders book This Town, but here he turns his eyes to the absurdities, excesses, scandals, and grime of the modern NFL machine, focusing primarily on the team’s owners, specifically the Patriots’ Robert Kraft and the Cowboys’ Jerry Jones.

A somewhat disheartening but occasionally hilarious follow-up to The League would be Mark Leibovich’s exposé Big Game: The NFL in Dangerous Times. Leibovich is, by trade, a political reporter famous for his Washington insiders book This Town, but here he turns his eyes to the absurdities, excesses, scandals, and grime of the modern NFL machine, focusing primarily on the team’s owners, specifically the Patriots’ Robert Kraft and the Cowboys’ Jerry Jones.

Leibovich’s worlds collide when the NFL has to dance around the gigantic figure of Donald Trump, whose own complicated history with the NFL make him delight in using the league as a pawn in his political games.

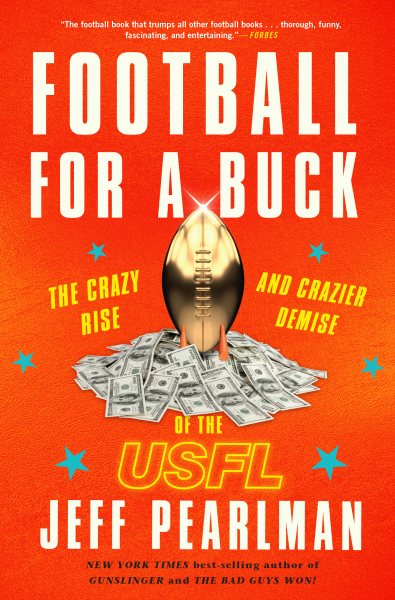

To find the origin story of that crazy tale, you could do worse than reading Jeff Pearlman’s engrossing history of the USFL, Football for a Buck. Pearlman has put out excellent biographies of Walter Payton and Brett Favre in recent years, but he is at his best when describing the widening gyres of an organization careening out of control, like he did when writing about the mid-90s Dallas Cowboys in Boys Will Be Boys.

To find the origin story of that crazy tale, you could do worse than reading Jeff Pearlman’s engrossing history of the USFL, Football for a Buck. Pearlman has put out excellent biographies of Walter Payton and Brett Favre in recent years, but he is at his best when describing the widening gyres of an organization careening out of control, like he did when writing about the mid-90s Dallas Cowboys in Boys Will Be Boys.

Here, Pearlman tells the story of the USFL, a popular spring football league in the 1980s conceived of by David Dixon, the idea man behind both the New Orleans Saints and the Superdome. The USFL originally had modest goals, but soon was locked in a spending war for bright stars. From this, it served as the launching pad for future stars Hershel Walker, Reggie White, Jim Kelly, and Steve Young. It was a victim of several years of chronic mismanagement, but its death knell was sounded when New York Generals owner Donald Trump pushed the USFL to move to an unsustainable fall schedule, in hopes of securing a NFL franchise of his own.

The final book I have to tell you about is Gridiron Genius: A Master Class in Winning and Building Dynasties in the NFL by Michael Lombardi. I’ve been a fan of Lombardi for years through his podcasts first with Bill Simmons and then on The Ringer. Before (and in the middle) of his media career, he has served as an NFL general manager and worked with football luminaries such as Bill Walsh, Al Davis, and Bill Belichick.

The final book I have to tell you about is Gridiron Genius: A Master Class in Winning and Building Dynasties in the NFL by Michael Lombardi. I’ve been a fan of Lombardi for years through his podcasts first with Bill Simmons and then on The Ringer. Before (and in the middle) of his media career, he has served as an NFL general manager and worked with football luminaries such as Bill Walsh, Al Davis, and Bill Belichick.

Lombardi’s book reads completely different than any other book on this list. In its DNA are the kind of ideas that permeate our business book section. Lombardi’s always been something of a polymath, so I think this is by design. Forget X’s and O’s. Forget star players. Lombardi is here to tell you that NFL teams are like any other organization, and that you have to create a “culture” if you’re interested in any sort of sustainable, deliberate success. Walsh’s 49ers and Belichick’s Patriots may be the greatest example the modern NFL has ever had. You may not get the opportunity to run an NFL team, but you might have the opportunity to run something else, and this book will help remind you to sweat the details.

So there you have it: 2018’s best bets for the professional football fan in your life. If you have somebody (or are somebody) who loves reading about football, you will surely find their next great read this Christmas somewhere on this list.

Like most millennials making connections in 2018, I found Jedidiah Jenkins through social media. As the editor of Wilderness magazine, Jedidiah filled

Like most millennials making connections in 2018, I found Jedidiah Jenkins through social media. As the editor of Wilderness magazine, Jedidiah filled  Key has returned with a metatextual sequel called

Key has returned with a metatextual sequel called  For the characters of Beth Kander’s

For the characters of Beth Kander’s  Although, effortless is a bit misleading. In interviews, conversations, and in the very content of the book, Laymon admits that Heavy was difficult to write. It was necessary. This duality persists throughout the layers of the memoir. The relationship Laymon describes with his mother is at times toxic, but is also nurturing, sincere, and life-giving. The relationship Laymon has with his own body and food moves between destructive and healthy. Growing up as a brilliant black child in Mississippi is both “burden and blessing,” to borrow Laymon’s own words. In the face of one-dimensional, monolithic, unimaginative stereotypes, Laymon spits nuance and grace and honesty—honesty that is gritty and soothing, that captures the “contrary states of the human soul,” as William Blake says.

Although, effortless is a bit misleading. In interviews, conversations, and in the very content of the book, Laymon admits that Heavy was difficult to write. It was necessary. This duality persists throughout the layers of the memoir. The relationship Laymon describes with his mother is at times toxic, but is also nurturing, sincere, and life-giving. The relationship Laymon has with his own body and food moves between destructive and healthy. Growing up as a brilliant black child in Mississippi is both “burden and blessing,” to borrow Laymon’s own words. In the face of one-dimensional, monolithic, unimaginative stereotypes, Laymon spits nuance and grace and honesty—honesty that is gritty and soothing, that captures the “contrary states of the human soul,” as William Blake says.

Hosseini’s newest book,

Hosseini’s newest book,  If They Come For Us is a collection of poems that tell the story of a young Pakistani Muslim woman who has grown up in America. Orphaned as a child, the speaker lives with her aunt and uncle. Her life is a very American mix of cultures, where she plays with Beanie Babies, eats badam, runs track, and reads the Qur’an. By day, she attends public school and tries to fit in with her blonde classmates. By night, she is told her family’s history of Partition and running from violence. Mixed with all of this are the growing up stories of every woman.

If They Come For Us is a collection of poems that tell the story of a young Pakistani Muslim woman who has grown up in America. Orphaned as a child, the speaker lives with her aunt and uncle. Her life is a very American mix of cultures, where she plays with Beanie Babies, eats badam, runs track, and reads the Qur’an. By day, she attends public school and tries to fit in with her blonde classmates. By night, she is told her family’s history of Partition and running from violence. Mixed with all of this are the growing up stories of every woman. Stephen Markley’s gripping debut novel

Stephen Markley’s gripping debut novel  So, even if he’s not like famous like a pop star or president, he’s had occasion over the past decade or so to consider the ramifications of fame, celebrity, and influence in our culture. And he’s put these ideas to use in his smart, fun debut novel An Absolutely Remarkable Thing.

So, even if he’s not like famous like a pop star or president, he’s had occasion over the past decade or so to consider the ramifications of fame, celebrity, and influence in our culture. And he’s put these ideas to use in his smart, fun debut novel An Absolutely Remarkable Thing.