By Don Jackson. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (May 20)

Southern storytelling is a beautiful art form. Through the ages it has been the glue that has bound us across generations. Although facts are always subject to questioning, the truth is always there. It becomes a shared truth that gives us strength and meaning within a framework of profound identity, and as a people with a common heritage.

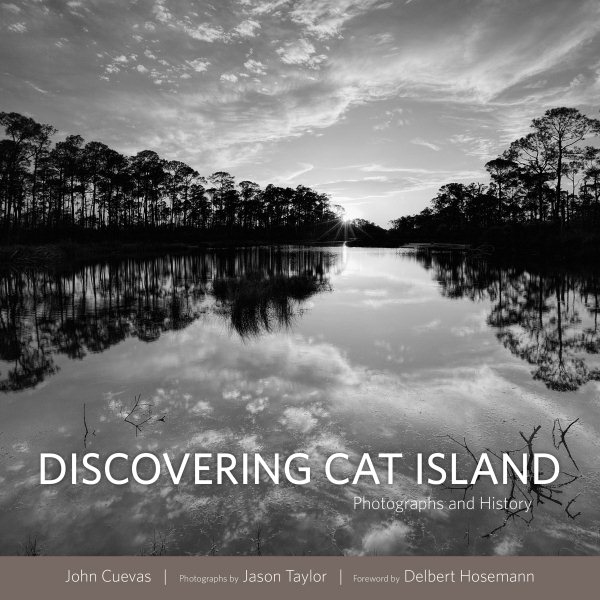

Such is the wonder and the power of Discovering Cat Island by John Cuevas. It gives us the story of a unique and fascinating place on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, and of the people who have been part of its history. It brings us light and shadows, and allows the reader to fill in the colors, both in prose and in photography.

Such is the wonder and the power of Discovering Cat Island by John Cuevas. It gives us the story of a unique and fascinating place on the Mississippi Gulf Coast, and of the people who have been part of its history. It brings us light and shadows, and allows the reader to fill in the colors, both in prose and in photography.

This is not a scholarly work created for academics, although it is rich in information and required extensive research. Rather, it is a story that will hold the reader transfixed, with wonderfully-written, almost poetic, prose. A word of warning here… Do not sit down with this book unless you are prepared to sit where you are for at least a couple of hours. You will not be able to put it down. You very likely will read the entire text in one sitting. I certainly did.

Typically I consider books like Discovering Cat Island as coffee-table books that allow one to leisurely pick up the volume and thumb through the photographs… easy to pick up… easy to put down. They provide opportunity for light, transient entertainment. They’re on the table as fillers, just there as something to do, while other things are going on. Interruptions don’t matter. Accordingly, I’m more inclined to spend time with the photographs in such books than I am with their text. Rarely will I even bother with the text.

But with Discovering Cat Island, it was just the opposite. The photography was excellent. But it was the text that kept me spellbound. I’m not sure why, but I broke my rule and started reading the text when I first got a copy of this book.

Once I did that I could not take time to look at the photographs as I desperately turned the pages to get beyond the photographs and to where the story continued.

Only afterward did I go back to look at the gorgeous black and white photography of Jason Taylor. And when I did this, those photographs provided rich seasoning for the story I’d just read. The echoes of the story reverberated deeply within me as I went page by page, slowly catching the spirit of each one of Taylor’s masterpieces.

I strongly suggest that this be the sequence for future readers of this book. Start with the story. But, don’t just read the story. Listen to it! After you’ve heard the story then, as it resonates within you, go back through the book and let the photographs etch this powerful story deeply into your heart.

It is, after all, your story too. Soon thereafter you will realize that this story must be shared with those near and dear to you… with a daughter, son, grandchild, or good friend… together in a porch swing, or out under a live oak, or in front of a fireplace, or wherever your special place may be.

Cat Island is and has for been for generations such a special place for so many people. So, why not just go there with that special someone and share the story there, together. Become part of that story, right there where it all happened and is happening. Pass it along through the tumbling generations for whom, in their hearts, the Deep South and its Gulf Coast is home. It really doesn’t matter whether or not you live here. Cat Island is part of your story. Come discover it.

Donald C. Jackson is the Sharp Distinguished Professor, Emeritus at Mississippi State University. He is Past President of the American Fisheries Society, Past President of the Mississippi Wildlife Federation, and has worked extensively with fisheries resources along the Mississippi Gulf Coast. He is the author of three collections of outdoor essays: Tracks, Wilder Ways and Deeper Currents.

Signed copies of Discovering Cat Island are available at Lemuria’s online store.

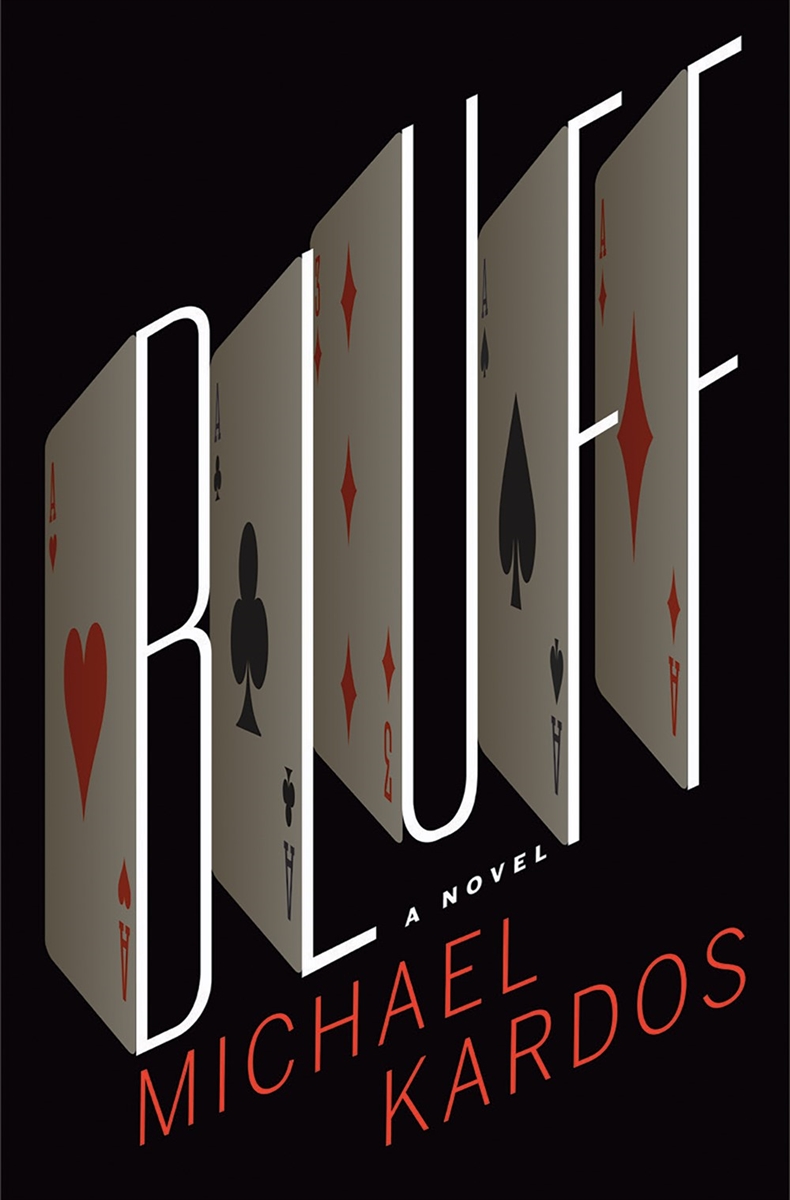

Set in Kardos’s native New Jersey, the novel starts with close-up magician Natalie Webb, on the verge of being washed up at 27, almost blinding a smarmy lawyer at a corporate holiday show by throwing a playing card at his eye. It’s a compelling and darkly funny opening, one that sets the tone for the rest of what’s to come: a book that expertly walks the line between breeziness and brutality.

Set in Kardos’s native New Jersey, the novel starts with close-up magician Natalie Webb, on the verge of being washed up at 27, almost blinding a smarmy lawyer at a corporate holiday show by throwing a playing card at his eye. It’s a compelling and darkly funny opening, one that sets the tone for the rest of what’s to come: a book that expertly walks the line between breeziness and brutality. Those are the questions readers will be asking themselves after the final page is turned in

Those are the questions readers will be asking themselves after the final page is turned in  The Fighter opens with a harrowing scene of high-speed DUI and pretty much never lets up from there. It’s the tale of a washed-up, alcohol- and pill-addicted cage fighter prepping for what will be his very last fight—either for good or ill. The stakes are life-or-death—no quarter asked or given. It is a brutal subculture of the South we know, but a fascinating one.

The Fighter opens with a harrowing scene of high-speed DUI and pretty much never lets up from there. It’s the tale of a washed-up, alcohol- and pill-addicted cage fighter prepping for what will be his very last fight—either for good or ill. The stakes are life-or-death—no quarter asked or given. It is a brutal subculture of the South we know, but a fascinating one. So plays out the message in Julie Cantrell’s latest novel,

So plays out the message in Julie Cantrell’s latest novel,  Just about midway through

Just about midway through  These qualities lie at the heart of an outstanding new work,

These qualities lie at the heart of an outstanding new work,  Tim Gautreaux’s career has been long and prolific, spanning three novels and two collections of short stories that have established him as one of the South’s finest writers. In his latest,

Tim Gautreaux’s career has been long and prolific, spanning three novels and two collections of short stories that have established him as one of the South’s finest writers. In his latest,