By Matthew Guinn. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (March 11)

“Do anything but bore me,” the late novelist Harry Crews once said in an interview.

“Tie me up and beat me with a motorcycle chain if you must, but don’t bore me.”

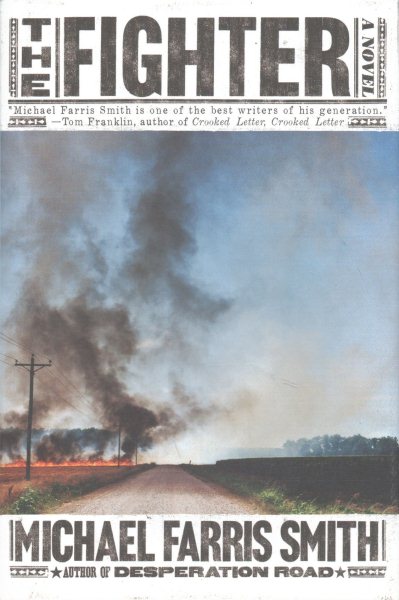

Mississippi writer Michael Farris Smith apparently shares that sentiment. Crews’ statement could be the mantra of The Fighter.

The Fighter opens with a harrowing scene of high-speed DUI and pretty much never lets up from there. It’s the tale of a washed-up, alcohol- and pill-addicted cage fighter prepping for what will be his very last fight—either for good or ill. The stakes are life-or-death—no quarter asked or given. It is a brutal subculture of the South we know, but a fascinating one.

The Fighter opens with a harrowing scene of high-speed DUI and pretty much never lets up from there. It’s the tale of a washed-up, alcohol- and pill-addicted cage fighter prepping for what will be his very last fight—either for good or ill. The stakes are life-or-death—no quarter asked or given. It is a brutal subculture of the South we know, but a fascinating one.

Jack, the titular fighter, should have turned out better. Though orphaned as a toddler, he was raised lovingly in Clarksdale by a devoted foster mother, Maryann (one of the most endearing characters in recent Southern fiction). And yet, as though driven by some kind of genetic predisposition, the teenaged Jack learns and loves the art of bare-knuckle boxing. Soon he is crisscrossing the Southeast for one underworld matchup after another. He climbs to the top of the heap.

But Jack’s champion status comes at a steep cost. He numbs the years of blows and undiagnosed concussions with painkillers and booze. The combined effect is a general amnesia that renders him vulnerable to the cunning. Add in his history of fixing or ‘throwing’ fights for gambling profit, and Jack becomes a walking disaster, a veritable tornado over himself. It is difficult to tell which came first—his pill or gambling addiction. Regardless, each feeds the other.

Enter Big Momma Sweet. In the world of The Fighter, predators are as common as the buzzards that dot the Delta sky, and Big Momma is the queen of them all. From her camp outside Clarksdale, she presides over an empire of fighting, gambling, drugs, and prostitution. Jack is her biggest debtor. His only prospect for settling up with her is one last prize fight—one he is woefully unprepared to fight, perhaps not even to survive.

And then there is a carnival that alights on Clarksdale: a touring regional fair full of convicts, gypsies, and a tattooed lady who just might prove to be Jack’s redemption.

If this synopsis sounds chaotic, frenetic, and over-the-top, then it is accurate. By conventional thinking, there is too much going on in The Fighter’s 256 pages for the short novel to bear. It should not work.

But it does. Smith’s narrative manages to stay just ahead of disintegration, and does so with style, lush prose, and storytelling assurance. Though its protagonist is a disaster, The Fighter is a triumph. It confirms Smith’s status as one of our foremost authors in the Rough South, Grit Lit tradition established by Crews, Larry Brown, Tom Franklin, William Gay, and the towering Cormac McCarthy.

The Fighter is Smith’s third novel in just five years, following 2017’s Desperation Road and 2013’s Rivers. That body of work has established Smith’s aesthetic: a naturalistic South of people living tough lives on the margins, where grace comes hard but the sad stories play out beautifully. All of Smith’s people are on one road or another toward an uncertain future. It will be a harrowing thrill to follow him farther down that road, with his characters just a single step—make that a half-step—ahead of destruction.

Novelist Matthew Guinn is the author of The Resurrectionist and The Scribe. He is associate professor of creative writing at Belhaven University.

Michael Farris Smith will be Lemuria on Thursday, March 22, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and read from The Fighter, which is one of Lemuria’s two March 2018 selections for our First Editions Club for Fiction.

Comments are closed.