By Seetha Srinivasan. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (June 23)

In the end a lifetime is not enough, the heart yearns for more. Who can reason with desire? The heart has its reasons that reason cannot know.

One day Sylvie will push open that curtained door to come to me, and despite all that I have known, at the sight of her I will finally believe that all losses are restored and sorrows end.

These words of Julien, the spectral protagonist of Mamta Chaudhry’s Haunting Paris, begin and conclude the novel, the crux of which is the story of the Jewish psychologist Julien and his lover, music teacher Sylvie. Haunting Paris is set in 1989 and recounts Sylvie’s search for Julien’s sister Clara’s daughter who vanished in war-time Paris. Clara and another daughter perished in the Holocaust. Julien, wracked with guilt for not being able to save his sister and her family, is convinced that one of his nieces is alive and spent years searching for her. After his death, a chance find of a letter impels Sylvie to continue Julien’s quest.

These words of Julien, the spectral protagonist of Mamta Chaudhry’s Haunting Paris, begin and conclude the novel, the crux of which is the story of the Jewish psychologist Julien and his lover, music teacher Sylvie. Haunting Paris is set in 1989 and recounts Sylvie’s search for Julien’s sister Clara’s daughter who vanished in war-time Paris. Clara and another daughter perished in the Holocaust. Julien, wracked with guilt for not being able to save his sister and her family, is convinced that one of his nieces is alive and spent years searching for her. After his death, a chance find of a letter impels Sylvie to continue Julien’s quest.

This is the barest outline of the plot. Like all fine fiction, it is in its unfolding that Haunting Paris captivates.

We witness the romance of the upper-class married Julien and his sensitive lover Sylvie, the lives of his children and his wife Isabelle (who will not give up Julien), Sylvie’s discovery of the letter that allows her to trace the lives of Clara and her daughters, and the fortuitous encounter that brings their story full circle.

Chaudhry narrates with sensitive attention the lives of her main characters and brings the same skill to drawing portraits of her entire cast, among them: the kindly concierge Ana Caravalho, sisters Marie and Mathilde who protect Clara and her daughters only to unwittingly betray them, and Sylvie’s American lodgers Alice and Will with their experiences of life in Paris.

The novel moves easily between its setting during celebrations of the bicentennial of the Revolution and the horrors of war-time Paris and Nazi atrocities. Chaudhry’s ability to sustain this structure even as she risks having a ghostly narrator is impressive.

The city seems almost a character in itself, and Chaudhry’s evocation of Paris is superb. Her ability to render telling details and convey the sights, sounds, and the very texture of life puts the reader at its center. Those who know Paris will revel in this marvelous re-creation; those who do not will finish the novel wishing to visit.

It is primarily through Julien’s eyes that we view Paris and its history. “But when the Bastille fell into their hands, they discovered half-a-dozen prisoners in the fortress, seven to be precise, and the faces of the freed men gaped at their jailer’s severed head, both wearing identical expressions of astonishment at this shift of power from the grasp of kings into the hands of the people.”

On the Eiffel Tower: “I admire the way its sequined lights shine like early stars in the dark, the filigreed ironwork making it seem to float weightlessly, for all its substance, an inspired emblem for the city of light—in both senses of the word—not just luminosity but also lightness, which we prize above all, in wit, in art, in life.”

Haunting Paris, with its complex and intriguing structure, carefully researched historical details woven with adroit and meticulous care into the narrative, deeply sympathetic characters whose story moves between mysteries of past and present showing the myriad ways in which the past never loses its hold, is indeed, as Kirkus noted: “an elegant debut.” It is also an absorbing must-read.

Seetha Srinivasan is the director emerita of the University Press of Mississippi.

Mamta Chaudhry will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, June 26, at 5:00 p.m. in a joint event with Alex Ohlin (author Dual Citizens) to sign and discuss Haunting Paris.

Born in London and growing up in points around the U.S., Chanelle Benz wound up discovering the Mississippi Delta–which would become the setting for her new novel

Born in London and growing up in points around the U.S., Chanelle Benz wound up discovering the Mississippi Delta–which would become the setting for her new novel

A member of the Blues Hall of Fame, Waterman managed, booked, and/or photographed essentially the entire Delta Blues revival as well as the electric blues apex of the 60s. Who else could write B.B. King’s biography, introduce unreleased Robert Johnson tracks to Eric Clapton, or receive an apology from Bill Graham? Guided by his level head and committed heart, Dick made many allies and musical history.

A member of the Blues Hall of Fame, Waterman managed, booked, and/or photographed essentially the entire Delta Blues revival as well as the electric blues apex of the 60s. Who else could write B.B. King’s biography, introduce unreleased Robert Johnson tracks to Eric Clapton, or receive an apology from Bill Graham? Guided by his level head and committed heart, Dick made many allies and musical history.

What was going to talk about here? Oh, yes. Joe Namath. Joe Willie. Broadway Joe. And, specifically, his new memoir,

What was going to talk about here? Oh, yes. Joe Namath. Joe Willie. Broadway Joe. And, specifically, his new memoir,

But Thompson doesn’t just “cover sports.” His is more a literary style that frames the athletes he writes about in a light most have never seen cast on these figures: the struggles, the hopes, the disappointments, and oftentimes the personal failures of men and women who know firsthand the high cost required to make it to the top – and attempt to stay there. Included are the stories of Michael Jordan, Bear Bryant, Ted Williams, and others who know the pain and joy of success in sports at its highest levels. Thompson ends the book with a memoir of his late father and his personal longings to honor his dad’s memory.

But Thompson doesn’t just “cover sports.” His is more a literary style that frames the athletes he writes about in a light most have never seen cast on these figures: the struggles, the hopes, the disappointments, and oftentimes the personal failures of men and women who know firsthand the high cost required to make it to the top – and attempt to stay there. Included are the stories of Michael Jordan, Bear Bryant, Ted Williams, and others who know the pain and joy of success in sports at its highest levels. Thompson ends the book with a memoir of his late father and his personal longings to honor his dad’s memory.

But if I told you Ocean Vuong’s novel debut

But if I told you Ocean Vuong’s novel debut  One summer in my twenties I worked as a deckhand on the Greenville, a towboat that plied the upper Mississippi River from Alton, Illinois to Davenport, Iowa. In that short span of time I came to understand the tremendous power of the river and the importance of its commerce. Melody Golding’s superb book,

One summer in my twenties I worked as a deckhand on the Greenville, a towboat that plied the upper Mississippi River from Alton, Illinois to Davenport, Iowa. In that short span of time I came to understand the tremendous power of the river and the importance of its commerce. Melody Golding’s superb book,

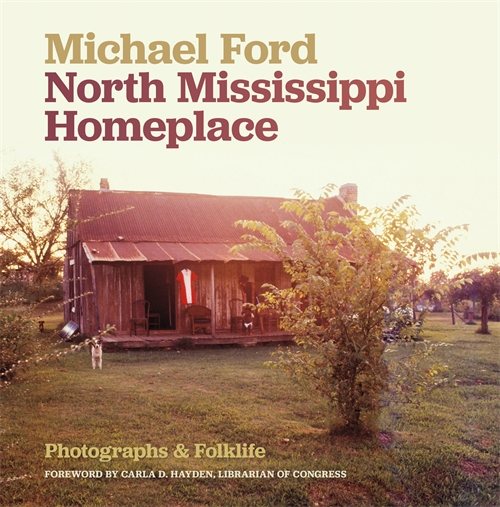

Now a filmmaker in Washington, D.C., Ford’s photo essays in his new book

Now a filmmaker in Washington, D.C., Ford’s photo essays in his new book

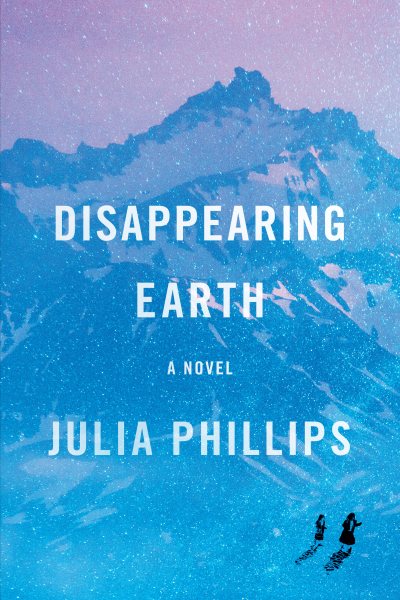

As a Brooklyn native who spent her college years studying the Russian language and who has long been fascinated with true stories of crime and violence–especially those within an ethnic or gender context–writer Julia Phillips presents

As a Brooklyn native who spent her college years studying the Russian language and who has long been fascinated with true stories of crime and violence–especially those within an ethnic or gender context–writer Julia Phillips presents