Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (July 9).

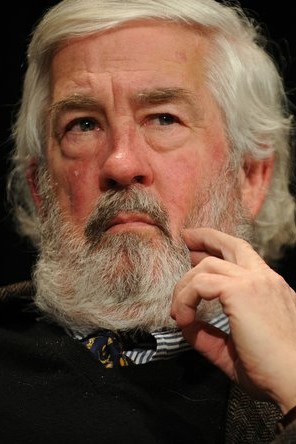

Curtis Wilkie

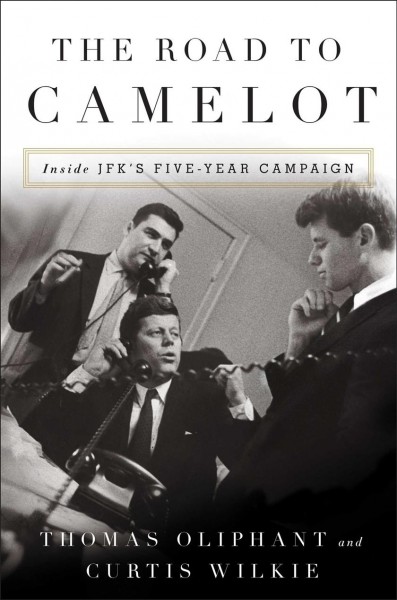

Mississippi’s iconic journalist and author Curtis Wilkie teams up with his long-time friend and former Boston Globe colleague, Pulitzer Prize winning reporter Thomas Oliphant, to bring a new generation of readers–as well as those who still remember the Kennedy/Nixon race of 1960–a wealth of new insights and behind-the-scenes information about one of the closest presidential contests in American history.

Their deeply-detailed account of how the Kennedy machine built and sustained the well-organized long game that carried JFK to victory in 1960 is carefully outlined in The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign (Simon & Schuster).

Beginning on page 1 with a blunt explanation of how the timing of the heart attacks of sitting President Dwight Eisenhower and then-Texas Senator Lyndon B. Johnson affected the 1956 race before it even started, Wilkie and Oliphant set a quick pace that covers a lot of political ground in 360-plus pages. As “one of the most vigorous campaign stories of all time,” it helps put today’s political climate in historical context.

Wilkie, a Greenville native and award-winning journalist who spent nearly four decades covering national and international news (including eight presidential elections and the South’s Civil Rights struggles), now teaches journalism at his alma mater, Ole Miss.

He authored four other books, including Assassins, Eccentrics, Politicians and Other Persons of Interest and The Fall of the House of Zeus.

Oliphant wrote for the Boston Globe as a political reporter for 40 years, and has authored four previous books, including Baseball as a Road to God and Utter Incompetents: Ego and Ideology in the Age of Bush.

Wilkie will appear at the Mississippi Book Festival Aug. 19 as a participant in the U.S. Presidents panel at 1:30 p.m. in the Old Supreme Court Room in the Mississippi Capitol Building in Jackson.

Your new book The Road to Camelot: Inside JFK’s Five-Year Campaign revisits the 1960 presidential campaign that ultimately landed John F. Kennedy in the White House. Why did you two decide to return once more to this story that played out more than half a century ago?

In 2003, I had an idea to write a book about one dramatic afternoon at the 1956 Democratic convention when Kennedy challenged the party establishment and nearly became the vice presidential nominee after Adlai Stevenson asked the delegates to choose his running mate. Even though he lost, Kennedy emerged as a new political star. As a teenager watching the struggle on TV, I had been fascinated. It was the last time any convention has gone past a first ballot.

In 2003, I had an idea to write a book about one dramatic afternoon at the 1956 Democratic convention when Kennedy challenged the party establishment and nearly became the vice presidential nominee after Adlai Stevenson asked the delegates to choose his running mate. Even though he lost, Kennedy emerged as a new political star. As a teenager watching the struggle on TV, I had been fascinated. It was the last time any convention has gone past a first ballot.

But no publishing house seemed interested in resurrecting that convention. I even got an audience with Alice Mayhew, the legendary editor at Simon & Schuster, to make a pitch. “Not big enough,” she told me.

Fast forward a decade. My great pal Tom Oliphant–we were colleagues at the Boston Globe for more than 25 years–told me of conversations he had with Ted Sorensen, one of Kennedy’s closest aides, who lamented that in all of the Kennedy corpus of books no one had written an account of the long campaign for the presidency. Teddy White wrote a great book about 1960, but it only dealt with one year. Bingo. We developed a bigger, broader book proposal and a number of houses bid on it. Alice Mayhew won the auction.

Kennedy’s five-year national campaign for president started immediately following his failed attempt to secure the VP spot on the Democrats’ ticket in 1956. At that time, he was a Massachusetts senator without a lot of national recognition. Why did he begin so early?

JFK had always started his campaigns early. When he first ran for Congress in 1946 he outflanked a number of older candidates by getting a head start.

Although John F. Kennedy’s father Joseph Kennedy was one of Boston’s most powerful, wealthy, and politically savvy business tycoons, JFK seemed to have an innate understanding of how to craft his own energetic run for the presidency. Tell me about JFK’s relationship with his father, and how it influenced his life.

No question JFK loved his father. He used his money to finance his campaign. But he disregarded virtually every recommendation the old man had. Joe Kennedy believed his son could win the presidential nomination the old-fashioned way–by getting the support of a handful of power-brokers. Instead, JFK took his campaign to the people in primaries.

One example: Joe Kennedy warned him to avoid the West Virginia primary–too many Protestants lived there who would be dubious of a Catholic. JFK defied his advice, entered and won this pivotal contest. Aside from frequent disagreements over strategy, the father complained that he could no longer talk about foreign policy with his son because their thoughts were so different.

Kennedy, who had surrounded himself with a group of bright, young advisers, preferred a grassroots approach over working with party bosses. Why was this?

Again, this was an example of Kennedy’s approach to elections. He always developed his own loyal organizations and ran outside the party structure. In Massachusetts, JFK had “Kennedy clubs” in virtually every town in the state. When he went national he did the same thing, attracting energetic followers early in each state. By the time potential rivals such as Lyndon Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, Stuart Symington, and Adlai Stevenson decided to grab for the presidential nomination, it was too late.

The 1960 campaign was the first to fully utilize the medium of television, and Kennedy became a master of exploiting the use of TV to his advantage. This was never so obvious as when he engaged in a series of debates with his Republican opponent, Richard Nixon. Explain why television–and those debates in particular–were so pivotal in this campaign.

Because he was charismatic, Kennedy was made for TV. He was our first television candidate. Nixon, meanwhile, looked like he had been sleeping under a bridge. Kennedy understood the medium and was the first candidate to hire media advisers. Substantively, there was really little difference between Kennedy and Nixon. Despite a widespread belief that Kennedy “won” the debates, we discovered during our research at the Kennedy Presidential Library that JFK’s private polls showed that the four debates never really changed the horse race between the two men.

Tell me about the strategy Kennedy used in the campaign to reach out to voters in the South, where Civil Rights and school integration were hot button issues.

As a Southerner, I was naturally interested in this aspect of the Kennedy campaign. Remember at the time that the South was still completely Democratic, but the Southern Democrats were very conservative and most of them were segregationists. Blacks were essentially unable to vote in the South, yet they represented an important constituency in so many of the big Northern states in an arc that ran from New York to places like Illinois and Michigan.

Kennedy walked a tightrope. He had always gotten along with most of the old Southern bulls in the Senate who were chairmen of committees because of their seniority. He had a good relationship, for example, with Senator Jim Eastland of Mississippi–and there were few senators more conservative than Eastland. In that 1956 convention fight, Kennedy wound up winning the support of most of the Southern delegations and that encouraged him to think he could make inroads in the South in 1960. I think he was sophisticated enough to realize that the Southern delegates voted for him in 1956 because he was an alternative to the ultimate victor for the vice presidential nomination, Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee. Kefauvcr was despised in the South because he was a liberal who opposed segregation.

Kennedy made a memorable trip to Jackson in 1957 and went all out to win support in the region. That was right after President Eisenhower was forced to send troops to Little Rock to ensure that court orders were enforced to desegregate Central High School there. Throughout the South, Kennedy was repeatedly asked for a commitment to never back up desegregation orders with troops. Eventually, it became clear that the Southern Democratic bosses preferred Lyndon Johnson, who was then Senate majority leader.

At the same time, Kennedy began to court black leaders in the North more avidly. He understood the importance of their votes. Against the advice of most of his advisers–including his brother Robert, who ran the campaign–JFK made a sympathetic telephone call to Coretta Scott King, who feared for the life of her husband, Martin Luther King, after he had been sent to a Georgia prison on a trumped-up traffic charge. That may have been the most critical decision of the campaign, winning thousands of black votes while Nixon did nothing. Yet Kennedy wound up winning half of the Southern states.

Explain why Kennedy’s Catholicism was a potential political obstacle for a national campaign in America during this time.

Kennedy was forced to promise publicly that the Vatican would not dictate politics in America. In 1960, I was a junior at Ole Miss and I still have vivid memories of the campaign, but I had forgotten how enormous was the Catholic issue.

Billy Graham and other evangelical leaders such as Norman Vincent Peale were actually involved in a conspiracy with the Nixon campaign to prevent the election of a Catholic. Once Kennedy was elected, the issue disappeared. No one considers Catholicism a political problem today.

The last-minute selection of Texas senator Lyndon B. Johnson as Kennedy’s running mate was unexpected, and, for many Kennedy supporters, unwanted. The lengthy account in your book explaining how it came about is as complicated as it is fascinating. Can you boil it down to a brief explanation?

Boiled down, Kennedy needed the electoral votes of Texas, and LBJ’s help in other Southern states to win.

Nixon was a formidable opponent, and the election results turned out to be among the closest in history for a Presidential race. What have been the official explanations for such a close outcome?

No real “official” explanation, but both men were smart candidates with pockets of strength across the country. Nixon, for example, managed to win California even though Kennedy felt he would carry the state.

In today’s political climate, what do you believe may be some important lessons we can all take away from this real-life story from more than 50 years ago?

Kennedy effectively invented the modern presidential campaign. Running outside the party apparatus was a model for other successful candidates: Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama. One can even make an argument that Donald Trump used this same approach. Kennedy was the first to have his own pollster to offer guidance about issues and constituencies. He mastered television. He was the first to exploit the route of the primaries, which everyone uses today.

In The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels (Random House), Meacham reminds us that intense political turmoil and dissent are not new to the American scene, and however out of sorts might seem the body politic today, we’re going to come through it just fine.

In The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels (Random House), Meacham reminds us that intense political turmoil and dissent are not new to the American scene, and however out of sorts might seem the body politic today, we’re going to come through it just fine.

But it goes far beyond a simple retracing of his steps here and his return to Washington that resulted in massive changes in federal food programs for the poor.

But it goes far beyond a simple retracing of his steps here and his return to Washington that resulted in massive changes in federal food programs for the poor. In Ta-Nehisi Coates’ new book of essays

In Ta-Nehisi Coates’ new book of essays

In 2003, I had an idea to write a book about one dramatic afternoon at the 1956 Democratic convention when Kennedy challenged the party establishment and nearly became the vice presidential nominee after Adlai Stevenson asked the delegates to choose his running mate. Even though he lost, Kennedy emerged as a new political star. As a teenager watching the struggle on TV, I had been fascinated. It was the last time any convention has gone past a first ballot.

In 2003, I had an idea to write a book about one dramatic afternoon at the 1956 Democratic convention when Kennedy challenged the party establishment and nearly became the vice presidential nominee after Adlai Stevenson asked the delegates to choose his running mate. Even though he lost, Kennedy emerged as a new political star. As a teenager watching the struggle on TV, I had been fascinated. It was the last time any convention has gone past a first ballot. But if you live there, the pressures of the quotidian grind and the sum of your life choices catch up with you, just like everywhere else. If that’s where your problems have come to a head, the quietest, sleepiest city in North America will feel like a welcome escape, which is exactly the situation that Henry Garrett, the unwell protagonist of Brown’s A Thousand Miles from Nowhere finds himself in.

But if you live there, the pressures of the quotidian grind and the sum of your life choices catch up with you, just like everywhere else. If that’s where your problems have come to a head, the quietest, sleepiest city in North America will feel like a welcome escape, which is exactly the situation that Henry Garrett, the unwell protagonist of Brown’s A Thousand Miles from Nowhere finds himself in. Instead of exiting New Orleans mid-breakdown, J.D. Callahan, the protagonist of The Innocent Have Nothing to Fear, reluctantly marches right back into it. He is there for the 2020 Republican National Convention, where he is trying to squeeze a moderate underdog candidate Hilda Smith into the nomination against nationalist Armstrong George (a thinly veiled, even tamped-down, satire of Donald Trump). His own breakdown revolved around a bad break-up from a news anchor girlfriend and a crack-up on Meet the Press. That might seem like a small obstacle compared to Henry Garrett’s, but the scrutiny of politics has a way of

Instead of exiting New Orleans mid-breakdown, J.D. Callahan, the protagonist of The Innocent Have Nothing to Fear, reluctantly marches right back into it. He is there for the 2020 Republican National Convention, where he is trying to squeeze a moderate underdog candidate Hilda Smith into the nomination against nationalist Armstrong George (a thinly veiled, even tamped-down, satire of Donald Trump). His own breakdown revolved around a bad break-up from a news anchor girlfriend and a crack-up on Meet the Press. That might seem like a small obstacle compared to Henry Garrett’s, but the scrutiny of politics has a way of