by Trianne Harabedian

We received advanced copies of Claire Lombardo’s The Most Fun We Ever Had a few months ago, and it immediately went on my to-be-read list. Sometimes you just have a good feeling about a book. But I was consumed with middle grade novels and picture books, and, since I spend all my time in the children’s section, I didn’t feel like I could justify the commitment of such a thick adult novel. Finally deciding to be selfish was one of the best book choices I have made in a long time. This novel had everything I wanted, leaving me constantly thirsting for more and eventually satisfied. It was beautifully written, with lyrical prose that blended sarcastic dialogue with heartbreaking personal revelations. But the characters are truly what carries this novel. Though it shifts between the perspectives of all six Sorenson family members, there is not a moment that the novel loses the reader. It reads like the richest chocolate, decadence slowly melting into total captivation.

In the 1970s, rebellious Marilyn and straight-laced David fall in love by literally running into each other in a university hallway. Their life together unfolds into a strange domestic bliss when Marilyn becomes pregnant with their daughters in quick succession and decides not to finish undergrad. By 2016, when the book is set, their four daughters, Wendy, Violet, Liza, and Grace, are adults and living wildly different lives than their parents had envisioned.

In the 1970s, rebellious Marilyn and straight-laced David fall in love by literally running into each other in a university hallway. Their life together unfolds into a strange domestic bliss when Marilyn becomes pregnant with their daughters in quick succession and decides not to finish undergrad. By 2016, when the book is set, their four daughters, Wendy, Violet, Liza, and Grace, are adults and living wildly different lives than their parents had envisioned.

Wendy is a young widow who spends her days with bottles of red wine and younger men. Violet is a mother who gave up her career to give all of existence to her sons, which has resulted in emotional space between her and her husband. Liza has been living with her chronically depressed boyfriend for years, dividing her time between caring for him and her job as a newly tenured professor. And Grace, the youngest by quite a few years, is living far away and successfully lying to her family that she was accepted to law school.

The novel begins when Wendy rashly decides to find out what happened to the child Violet secretly gave up for adoption years earlier. It turns out that Jonah’s life has been far from the idyllic existence Violet had imagined. But while he is welcomed into the Sorenson family with open arms, his presence exposes cracks in their close-knit relationships. Marilyn is crushed that Violet and Wendy kept such a secret from their mother, creating the charade that Violet was studying abroad in France, and David feels as though he understands his daughters less than ever. Liza finds out that she is pregnant, therefore stuck in her loveless relationship forever, and Grace continues to spiral while assuring her parents that law school is just great. But the overpowering force in this book is familial love. Amidst sarcasm, screaming matches, feuds, and heartbreaking internal monologues, the Sorensons do love each other. And in the most non-cliche way, Claire Lombardo uses this lasting bond to not just repair their relationships, but to mature them in directions that ring true.

There are a million novels written about the middle-class American family. They are alike in their celebration of the mundane, in their biting dialogue and their delving into typical family drama. The Most Fun We Ever Had is not one of these novels. It takes the literary trend and turns it from dry rice to a full-course meal, complete with red wine and dark chocolate. It’s no secret that I love character-based novels. If I have to choose between an amazingly twisted plot and a long story that focuses on personal emotions and thoughts, I will always go with the latter. Give me a good family drama, complete with secret children, emotional affairs, and drunken monologues, and I’ll be happy. But I also love truly literary works. Thanks to Claire Lombardo, I don’t have to choose.

Signed first editions of The Most Fun We Ever Had by Claire Lombardo are available in our online store.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg’s book,

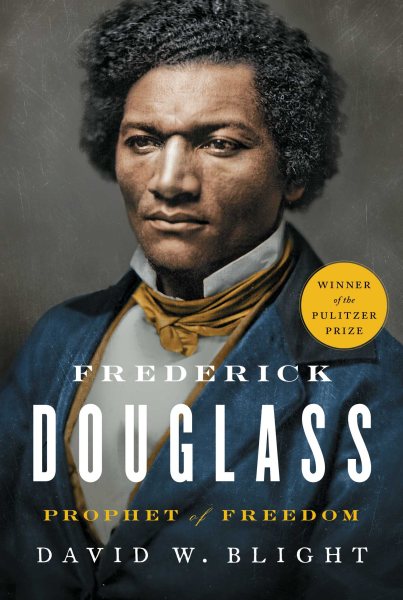

Raphael Bob-Waksberg’s book,  Blight’s biography, which won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in History, offers a similar intensity, but pulls the camera back to offer a wider-angle view. We are greeted with the larger political and social contexts through which Douglass’ life flowed, yet Blight’s writing never looses its focus on Douglass’ own experiences. Showing these intersections between national history and Douglass’ personal history allows Blight to muse on how Douglass’ writing and activism affected the American abolitionist movements, and how the various gears of those movements affected Douglass personally.

Blight’s biography, which won the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in History, offers a similar intensity, but pulls the camera back to offer a wider-angle view. We are greeted with the larger political and social contexts through which Douglass’ life flowed, yet Blight’s writing never looses its focus on Douglass’ own experiences. Showing these intersections between national history and Douglass’ personal history allows Blight to muse on how Douglass’ writing and activism affected the American abolitionist movements, and how the various gears of those movements affected Douglass personally. What was going to talk about here? Oh, yes. Joe Namath. Joe Willie. Broadway Joe. And, specifically, his new memoir,

What was going to talk about here? Oh, yes. Joe Namath. Joe Willie. Broadway Joe. And, specifically, his new memoir,

But if I told you Ocean Vuong’s novel debut

But if I told you Ocean Vuong’s novel debut  Knight’s new novel, set in 1994 at a boarding school in rural Virginia, is told from the perspective of Lenore Littlefield, a pregnant student of hidden talents and opaque motivations, and two lonely faculty members ostensibly charged with the education and guidance of Littlefield and her peers. The first person to whom Lenore reveals her predicament is her well-intentioned but somewhat indecisive history teacher, Lucas Bishop.

Knight’s new novel, set in 1994 at a boarding school in rural Virginia, is told from the perspective of Lenore Littlefield, a pregnant student of hidden talents and opaque motivations, and two lonely faculty members ostensibly charged with the education and guidance of Littlefield and her peers. The first person to whom Lenore reveals her predicament is her well-intentioned but somewhat indecisive history teacher, Lucas Bishop. Roommates in college, Helen and Charlie were opposite forces who became incredibly close. Helen was more scientific and analytical, a quiet woman who made herself known in the academic world, while Charlie was magnetic and outgoing. She was one of those people who everyone wanted to be around. After graduation, the women drifted apart. They both had children, Helen on her own and Charlie with a husband, and they made great strides in their professions. Helen became a theoretical physicist at MIT and published accessible books about physics, and Charlie became a screenwriter in Hollywood.

Roommates in college, Helen and Charlie were opposite forces who became incredibly close. Helen was more scientific and analytical, a quiet woman who made herself known in the academic world, while Charlie was magnetic and outgoing. She was one of those people who everyone wanted to be around. After graduation, the women drifted apart. They both had children, Helen on her own and Charlie with a husband, and they made great strides in their professions. Helen became a theoretical physicist at MIT and published accessible books about physics, and Charlie became a screenwriter in Hollywood. “But it’s a middle grade book,” I told myself. “It’s for ages nine to twelve. How scary can it be?” Not scary at all, as it turned out! In fact, I devoured it like pizza on a late night. It was the most engaging middle grade novel I’ve read in a long time.

“But it’s a middle grade book,” I told myself. “It’s for ages nine to twelve. How scary can it be?” Not scary at all, as it turned out! In fact, I devoured it like pizza on a late night. It was the most engaging middle grade novel I’ve read in a long time. Thomas returns to the fictional Garden Heights community of The Hate U Give in her follow-up novel, On the Come Up. In this book, 16-year-old Bri Jackson overcomes other people’s expectations for her to find her voice and use her talent for hip-hop to communicate her place in the world. From the “ring battles” in a local boxing gym to the SoundCloud-inspired accounts of the internet, Bri always goes forth boldly to remind the world that “when you say brilliant that you’re also saying Bri.”

Thomas returns to the fictional Garden Heights community of The Hate U Give in her follow-up novel, On the Come Up. In this book, 16-year-old Bri Jackson overcomes other people’s expectations for her to find her voice and use her talent for hip-hop to communicate her place in the world. From the “ring battles” in a local boxing gym to the SoundCloud-inspired accounts of the internet, Bri always goes forth boldly to remind the world that “when you say brilliant that you’re also saying Bri.” Rayne and Delilah’s Midnite Matinee

Rayne and Delilah’s Midnite Matinee