Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (September 2)

Sorority recruitment (that still translates as “rush” at most Southern universities) can be a pivotal time for freshmen college women, but is probably approached with more reverence, tradition, and passion at Ole Miss than perhaps any other campus–anywhere.

And that’s where bestselling author Lisa Patton, a Memphis native, current Nashville resident and graduate of the University of Alabama, chose to set her newest novel, Rush.

And that’s where bestselling author Lisa Patton, a Memphis native, current Nashville resident and graduate of the University of Alabama, chose to set her newest novel, Rush.

Written with amazing attention to detail and as much humor as heart, Rush takes readers behind the doors of the of the school’s fictional Alpha Delta Beta house, where the newest pledge class fights for civil justice for their house staff despite opposition from the sisterhood’s scheming house corp president. Along the way, a handful of diverse characters slowly reveal their own secrets, fears, and hopes as their lives are linked together.

Lisa Patton

Before her writing career, Patton worked as a manager and show promoter for the historic Orpheum Theatre in Memphis and as part of the promotion teams for radio and TV stations in the Bluff City. She later worked on album and video projects with Grammy Award-winning musician Michael McDonald.

It was a three-year stint as an innkeeper in Vermont that inspired her first novel, Whistlin’ Dixie in a Nor’Easter, which was followed by Yankee Doodle Dixie (both featured on the Southern Independent Booksellers Alliance Bestseller List); and Southern as a Second Language.

The mother of two sons, Patton and her husband now live in Nashville.

Rush–an eye-opening inside story about life in an Ole Miss sorority house–is so full of spot-on details about the young women who go through recruitment, or “rush,” and the houses they call their campus homes, that it’s hard to believe you weren’t a student at Ole Miss yourself. Why did you choose to write about Greek life at the University of Mississippi, and not the school you attended–the University of Alabama?

I went back and forth about which campus was best for the setting. Both universities are historical and breathtakingly gorgeous, but I ultimately chose Ole Miss because the town of Oxford provided a more colorful backdrop to the story. Many Ole Miss graduates hail from Memphis, and as a native Memphian I love including my hometown in my novels.

During my writing process, Eli Manning received the Walter Payton Humanitarian of the Year Award. I’d read that he and his wife, Abby, are well known philanthropists, and I though they would be perfect bit characters for the story. In truth, through, Rush could have been told on any Southern campus. Ole Miss won because it’s a darn good place to be! And quintessentially Southern.

Researching this book must have been fun! How did you find out about so many details of the secrets of sorority life at Ole Miss–like the name of the popular dorm, the schedules for rush week, the size of the sororities, etc.?

Goodness knows I tried. I spoke with several Ole Miss current students and recent graduates. I interviewed Ole Miss alumnae, Ole Miss housemothers, and a former Ole Miss housekeeper. The research was the best apart about writing Rush. I got to know many strong, wonderful women. Through our many phone calls and texts, I came to love and admire each of them and now call them my friends. In the last three years, I’ve spent a great deal of time on the Ole Miss campus. I honestly think of myself as half Rebel!

Your characters are plentiful, and very well developed–and many have secrets they’re trying hard to overcome. How were you able to create so many characters with their own stories to tell, and then weave them into the plot so well?

I was determined to give my characters complexity. So I gave thought to my own life and the lives of other vulnerable women I know, and analyzed what makes us real. We all have flaws, both moral and psychological, whether we want to admit them or not. So, after creating my characters, I talked with each one of them and asked for complete honesty. I took notes, as if I was their therapist, and learned all about their secrets! That might sound crazy, but it’s true.

Weaving them together was the easy part. Making the decision to finish the book was another story all together. When you take a stand for something you believe in with all your heart, resistance throws every fiery dart in its arsenal your way. I almost quite before Rush was born.

There are a lot of heartaches and problems facing the main characters–and keeping up with them is made much easier by how you structured the narration, which changes with each chapter, giving readers multiple first-person accounts of what rush and sorority life are like, filtered through each person’s point of view. Is this a writing technique you’ve used with your other books?

I’ve never written a book with multiple points of view before, but I felt it was a necessity for Rush. I wanted to give my readers an in-depth peek into sorority life, whether they were Greek or not. Cali is my 18-year-old freshman from small-town life–Blue Mountain, Mississippi. Memphis-born Wilda is an Ole Miss alum and mother to Ellie, who is rushing and living in Martin Dormitory. And Miss Pearl is the housekeeper of the fictional Alpha Delta Beta sorority house and second mom/counselor to the sorority sisters. When the story opens, they don’t know one another, but all that changes quickly.

At the center of the story is “Miss Pearl,” who practically runs the sorority house, and has for 25 years, but her chances of being promoted to house director are threatened by the racist attitudes of another character. Why this dominant topic, and why now?

I’m that child of the 60s and 70s. That little Southern girl who was bathed in motherly love by a woman who worked as a long-term housekeeper and cook for my family. Then I left for college and received a similar love from the women who worked in my sorority house. When I went back for a visit 38 years later, I noticed that much was still the same with regard to the house staff.

Some of the workers, men and women, spend decades of their lvies in these positions. It never once crossed my mind to inquire about their pay, their benefits, or their opportunity for promotion. When I discussed it with my sorority sisters, they agreed that it was an unfortunate oversight. We, as sorority women, are strong leaders. We are philanthropic and compassionate. WE strive to make things right. I’m hoping readers will get to know my characters, learn about their lives and understand their worlds better. My prayer is that Rush opens the door to discussion and is ultimately, perhaps, a vehicle for change.

What was your own sorority experience like at the University of Alabama?

It was one of the best times of my life. I made friendships that have lasted for decades and will last until I take my final breath. Whenever I look back on our college days, when we were all together, I get teary. Not only was it fun, maybe too fun at times, but it helped cement the values I’d learned in childhood and carry them with me through adulthood. I learned the importance of philanthropy, service, and leadership, and that’s only the beginning.

You began your career as a music producer and eventually became a full-time writer. Tell me about how that came about–and how you believe your writing has progressed through the years.

Because of my deep love for music, I was always attracted to jobs in the music industry. For many years, I worked for Michael McDonald of Doobie Brothers fame. He was the one who encouraged me to finish my first book and I, fortunately, took his advice. I wrote by the seat of my pants for the first three novels, but for Rush, I made a detailed outline. I also studied books on the craft of writing.

Do you have another writing project in the works now?

I do, thank you for asking! It’s a story about two teachers. Set in Memphis, it’s told in current day and looks back to the 1930s. Few people alive today remember a time when teachers couldn’t be married. It’s actually the first book I wanted to write but knew I needed more experience. I’m finally ready.

Lisa Patton will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, September 5, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and read from Rush.

Monument opens with a kind of instruction manual for how to read this collection of old and new poems. “Ask yourself what’s in your heart,” she writes, “that / reliquary—blood locket and seedbed—and contend with what it means.” This book, at its heart, is history contended—personal history, certainly, but also the history of a complicated southern landscape and Trethewey’s place within its legacy.

Monument opens with a kind of instruction manual for how to read this collection of old and new poems. “Ask yourself what’s in your heart,” she writes, “that / reliquary—blood locket and seedbed—and contend with what it means.” This book, at its heart, is history contended—personal history, certainly, but also the history of a complicated southern landscape and Trethewey’s place within its legacy.

From 1920 until 1933, Prohibition was the federal law of the land, banning alcohol across the country. But in Memphis, Prohibition lasted under state laws from 1909 until 1939. On page after page, author Patrick O’Daniel shows that Prohibition “led to increased crime, corruption, health problems and disrespect for all laws for three decades.”

From 1920 until 1933, Prohibition was the federal law of the land, banning alcohol across the country. But in Memphis, Prohibition lasted under state laws from 1909 until 1939. On page after page, author Patrick O’Daniel shows that Prohibition “led to increased crime, corruption, health problems and disrespect for all laws for three decades.” Key has returned with a metatextual sequel called

Key has returned with a metatextual sequel called  Although, effortless is a bit misleading. In interviews, conversations, and in the very content of the book, Laymon admits that Heavy was difficult to write. It was necessary. This duality persists throughout the layers of the memoir. The relationship Laymon describes with his mother is at times toxic, but is also nurturing, sincere, and life-giving. The relationship Laymon has with his own body and food moves between destructive and healthy. Growing up as a brilliant black child in Mississippi is both “burden and blessing,” to borrow Laymon’s own words. In the face of one-dimensional, monolithic, unimaginative stereotypes, Laymon spits nuance and grace and honesty—honesty that is gritty and soothing, that captures the “contrary states of the human soul,” as William Blake says.

Although, effortless is a bit misleading. In interviews, conversations, and in the very content of the book, Laymon admits that Heavy was difficult to write. It was necessary. This duality persists throughout the layers of the memoir. The relationship Laymon describes with his mother is at times toxic, but is also nurturing, sincere, and life-giving. The relationship Laymon has with his own body and food moves between destructive and healthy. Growing up as a brilliant black child in Mississippi is both “burden and blessing,” to borrow Laymon’s own words. In the face of one-dimensional, monolithic, unimaginative stereotypes, Laymon spits nuance and grace and honesty—honesty that is gritty and soothing, that captures the “contrary states of the human soul,” as William Blake says. While this “modern day reinterpretation” of the classic book has retained many favorite recipes from the original, it is filled with popular choices from recent editions of Southern Living magazine, and many of Heiskell’s own favorites. Menus include appetizers, main dishes, drinks, and desserts for a Bridal Tea, Garden Club Luncheon, Summer Nights, Cocktails and Canapés, Tailgate, Picnic on the Lawn, Fall Dinner, and 24 more occasions.

While this “modern day reinterpretation” of the classic book has retained many favorite recipes from the original, it is filled with popular choices from recent editions of Southern Living magazine, and many of Heiskell’s own favorites. Menus include appetizers, main dishes, drinks, and desserts for a Bridal Tea, Garden Club Luncheon, Summer Nights, Cocktails and Canapés, Tailgate, Picnic on the Lawn, Fall Dinner, and 24 more occasions.

It’s a fascinating voyage into the Golden Age of Piracy that not only proves true some of the stereotypes of legend, book and film, but also debunks others and shockingly reveals the depth of early America’s connection to the outlaw seafarers.

It’s a fascinating voyage into the Golden Age of Piracy that not only proves true some of the stereotypes of legend, book and film, but also debunks others and shockingly reveals the depth of early America’s connection to the outlaw seafarers. And that’s where bestselling author Lisa Patton, a Memphis native, current Nashville resident and graduate of the University of Alabama, chose to set her newest novel,

And that’s where bestselling author Lisa Patton, a Memphis native, current Nashville resident and graduate of the University of Alabama, chose to set her newest novel,

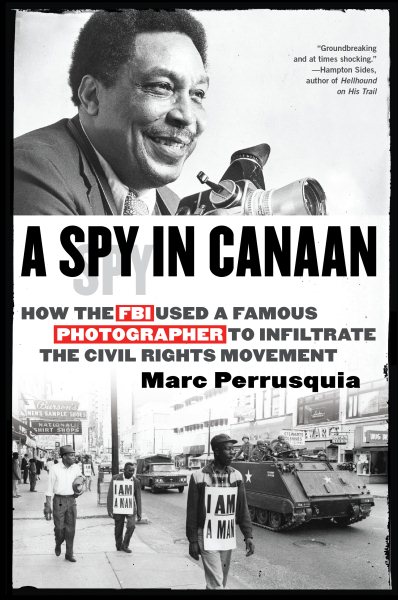

As a reporter for The Commercial Appeal, Perrusquia caught wind of a tantalizing story: that one of Memphis’ most well-known and respected Beale Street residents who had rubbed shoulders with the highest leaders of the movement was for nearly 20 years an FBI informant.

As a reporter for The Commercial Appeal, Perrusquia caught wind of a tantalizing story: that one of Memphis’ most well-known and respected Beale Street residents who had rubbed shoulders with the highest leaders of the movement was for nearly 20 years an FBI informant. The plots of White’s stories, when summarized, sound like the standard fare of short literary fiction. Lovers endure a strained vacation in the touristy Tennessee mountains; an angry father stares down his impending death; a young boy makes a brave choice that results in an uncomfortable coming of age. But in White’s hands, these small personal dramas are spiked with edgy hilarity.

The plots of White’s stories, when summarized, sound like the standard fare of short literary fiction. Lovers endure a strained vacation in the touristy Tennessee mountains; an angry father stares down his impending death; a young boy makes a brave choice that results in an uncomfortable coming of age. But in White’s hands, these small personal dramas are spiked with edgy hilarity. In his daring second novel,

In his daring second novel,