Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (June 30)

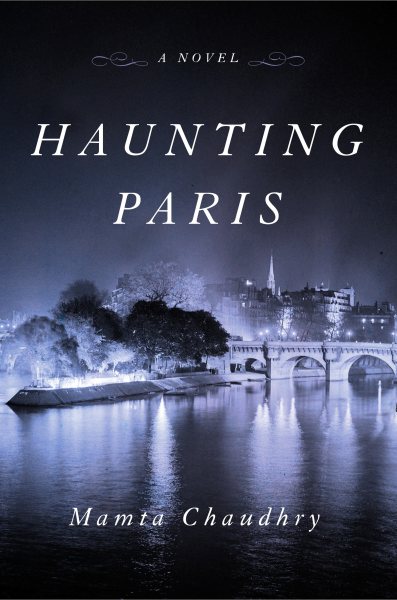

Mamta Chaudhry’s busy career has taken her from TV and radio stints to published fiction, poetry and feature writing, and with the release of her debut book, Haunting Paris, she happily adds the label of “novelist” to her achievements.

Mamta Chaudhry’s busy career has taken her from TV and radio stints to published fiction, poetry and feature writing, and with the release of her debut book, Haunting Paris, she happily adds the label of “novelist” to her achievements.

Chaudhry’s work has appeared in the Miami Review, The Illustrated Weekly of India, The Telegraph, The Statesman, Writer’s Digest, and The Rotarian, among others.

A native of Calcutta, India, she and her husband now live in Coral Gables, Fla. They enjoy spending part of each year in India and France.

Since this is your debut novel, please tell me a little about yourself–where did you grow up, your education, what brought you to Florida, family info, and what drew your interest in writing–whatever you would like to include.

Mamta Chaudhry

Even as a child, I always had my nose in a book, and pretty early on I also always had ink stains on my fingers, because I knew that I wanted to write books as well as read them. Fortunately for me, Calcutta–where I was born and brought up–is a book-loving city, with libraries, bookshops, and bookstalls everywhere.

After I graduated from Loreto College, I came to the States for a master’s degree in Journalism and Communications at the University of Florida. I met my husband in one of my classes, and among the many things that attracted me to Daniel is that he loves to read.

For many years, I worked in classical radio as an on-air host and programmer. Because I’m from India, people were always surprised to hear that I was a “deejay,” not a doctor. After I got my doctorate at the University of Miami, I now just nod when people ask if I’m a doctor–without adding I’m a doctor of English. Books also cure a lot of what ails the world.

Haunting Paris is your first novel, and it is packed with details about the city of Paris in its bicentennial year of 1989 (when the story takes place); and the events that unfolded in the city during World War II. How did you become interested in Paris, specifically during these two time periods?

When I start writing, I seldom set out with a place and time in mind. I’m usually transfixed by an image, or an overheard snatch of conversation, and then follow that wherever it takes me. I’ve been in love with Paris for a very long time, and when I began Haunting Paris, I quickly discovered that just as the City of Light has its own dark shadows, so France also sometimes falls short of its tripartite promise of Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité (Freedom, Equality, Fraternity). It seemed natural to link the bicentennial celebration of the French Revolution, where that inspiring motto originated, with a time when that promise was broken. So, 1989 and 1942 became two of the anchoring dates for the story.

The book focuses on the love story between main characters Julien (a married, Jewish psychiatrist) and Sylvie, (a pianist who is 24 years his junior and stirs him to reconsider his priorities in life). What brings these two together, and what makes their love “work” in this story?

What makes love work between any two people is one of the great mysteries of life. As Sylvie herself reflects, other people’s marriages are unknowable to outsiders. But it’s clear that despite his best intentions, Julien falls in love with Sylvie precisely because of what he feels is missing in his “perfect” marriage: her compassion and her courage. And one of the things that brings them together, time and again, is their shared love of music.

It was after Julien’s death that he becomes a “revenant” who watches over Sylvie. Explain the meaning of that word, especially as it relates to his role in this story.

Behind the Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, just beside the Seine, is an underground memorial to those who were deported during the dark days of the Nazi occupation of the city. On the floor, a bronze circle is chiseled with the words: “They went to the other end of the earth and they did not return.”

The end of the earth, the final threshold from which the absent never return. Or do they? My hair rose as I recalled the French word for ghost: revenant, one who returns. So, this is a ghost story, but the ghost is not frightening at all; on the contrary, he is drawn back by love.

Sylvie grieves deeply after Julien’s death, but eventually begins to put her life back together after she finds a mysterious letter in his private desk. Could you give readers a brief explanation of what she finds in that desk and how it helps her deal with her loss?

When Sylvie accidentally dislodges some papers hidden in a secret drawer, at first she is reluctant to follow up the discovery and also hurt that Julien has concealed something from her.

There’s something so mysterious, so uncanny, when you come across a secret–a letter in this instance–that is not meant for your eyes, and the only person you can ask about it can no longer speak to you. But then she wonders if she was meant to find it, and that fateful discovery sets her off on a quest that leads her deep into the secrets of Julien’s past and sheds new light on his character and on the city they both called home.

What is your next writing project that readers can look forward to?

I’m working on another novel and I can’t tell what it is until it’s finished, except to say that once again I’m transfixed by certain images and certain voices, and they are leading me to a completely different time and place from Haunting Paris.

Signed copies of Haunting Paris are still available at Lemuria’s online store.

Born in London and growing up in points around the U.S., Chanelle Benz wound up discovering the Mississippi Delta–which would become the setting for her new novel

Born in London and growing up in points around the U.S., Chanelle Benz wound up discovering the Mississippi Delta–which would become the setting for her new novel

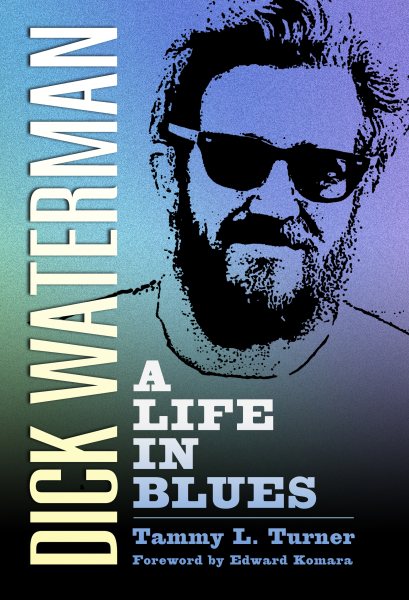

It was about a decade after music professor Tammy L. Turner met blues promoter/producer Dick Waterman in a class at Ole Miss that she came to realize “he had an important story that needed to be told,” and she has captured his extraordinary career in the memoir,

It was about a decade after music professor Tammy L. Turner met blues promoter/producer Dick Waterman in a class at Ole Miss that she came to realize “he had an important story that needed to be told,” and she has captured his extraordinary career in the memoir,

But Thompson doesn’t just “cover sports.” His is more a literary style that frames the athletes he writes about in a light most have never seen cast on these figures: the struggles, the hopes, the disappointments, and oftentimes the personal failures of men and women who know firsthand the high cost required to make it to the top – and attempt to stay there. Included are the stories of Michael Jordan, Bear Bryant, Ted Williams, and others who know the pain and joy of success in sports at its highest levels. Thompson ends the book with a memoir of his late father and his personal longings to honor his dad’s memory.

But Thompson doesn’t just “cover sports.” His is more a literary style that frames the athletes he writes about in a light most have never seen cast on these figures: the struggles, the hopes, the disappointments, and oftentimes the personal failures of men and women who know firsthand the high cost required to make it to the top – and attempt to stay there. Included are the stories of Michael Jordan, Bear Bryant, Ted Williams, and others who know the pain and joy of success in sports at its highest levels. Thompson ends the book with a memoir of his late father and his personal longings to honor his dad’s memory.

Now a filmmaker in Washington, D.C., Ford’s photo essays in his new book

Now a filmmaker in Washington, D.C., Ford’s photo essays in his new book

As a Brooklyn native who spent her college years studying the Russian language and who has long been fascinated with true stories of crime and violence–especially those within an ethnic or gender context–writer Julia Phillips presents

As a Brooklyn native who spent her college years studying the Russian language and who has long been fascinated with true stories of crime and violence–especially those within an ethnic or gender context–writer Julia Phillips presents

His long career has included more than 40 works of everything from poetry to fiction, nonfiction and screenplays–in addition to journalistic writing.

His long career has included more than 40 works of everything from poetry to fiction, nonfiction and screenplays–in addition to journalistic writing. “My sense of narrative really came from watching late night black and white films on television and growing up in hotels, mostly among adults,” Gifford said. “I was able to listen to all of their stories, make up my own and absorb a variety of dialects. Moving around added to the mix. Being in the company of my father’s friends, most of whom had dubious occupations, served to supply the intrigue.”

“My sense of narrative really came from watching late night black and white films on television and growing up in hotels, mostly among adults,” Gifford said. “I was able to listen to all of their stories, make up my own and absorb a variety of dialects. Moving around added to the mix. Being in the company of my father’s friends, most of whom had dubious occupations, served to supply the intrigue.”

Oxford’s Mary Miller highlights a Mississippi coastal town with a thoughtful tale of a middle-aged man facing an uncertain and lonely future–until he adopts a dog on a whim and one thing leads to another.

Oxford’s Mary Miller highlights a Mississippi coastal town with a thoughtful tale of a middle-aged man facing an uncertain and lonely future–until he adopts a dog on a whim and one thing leads to another.

And although the celebrated author of

And although the celebrated author of

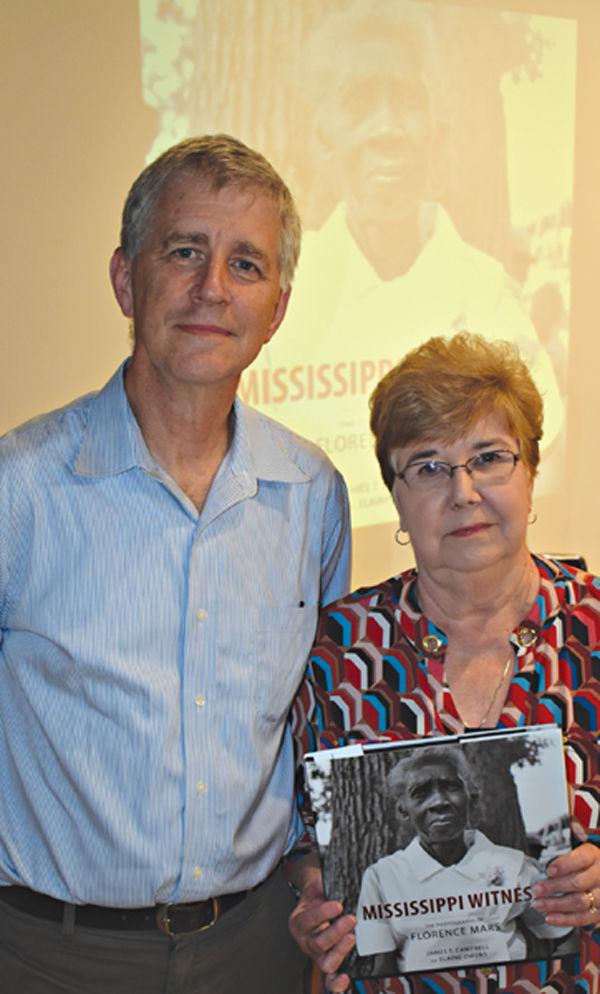

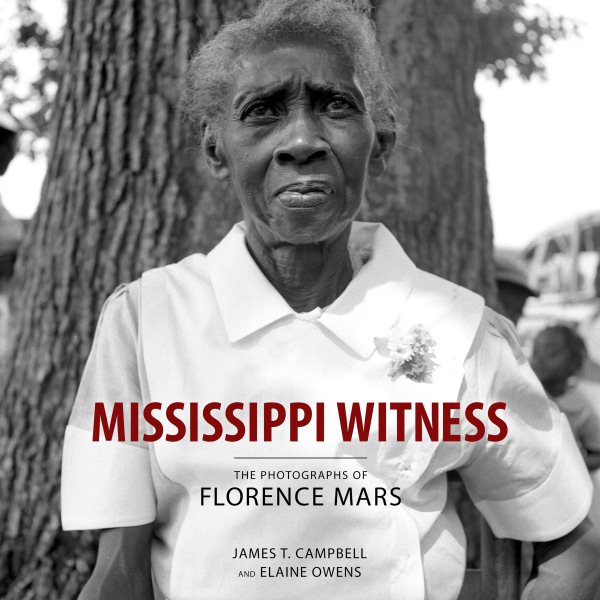

Mississippi Witness: The Photographs of Florence Mars

Mississippi Witness: The Photographs of Florence Mars