Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (November 24)

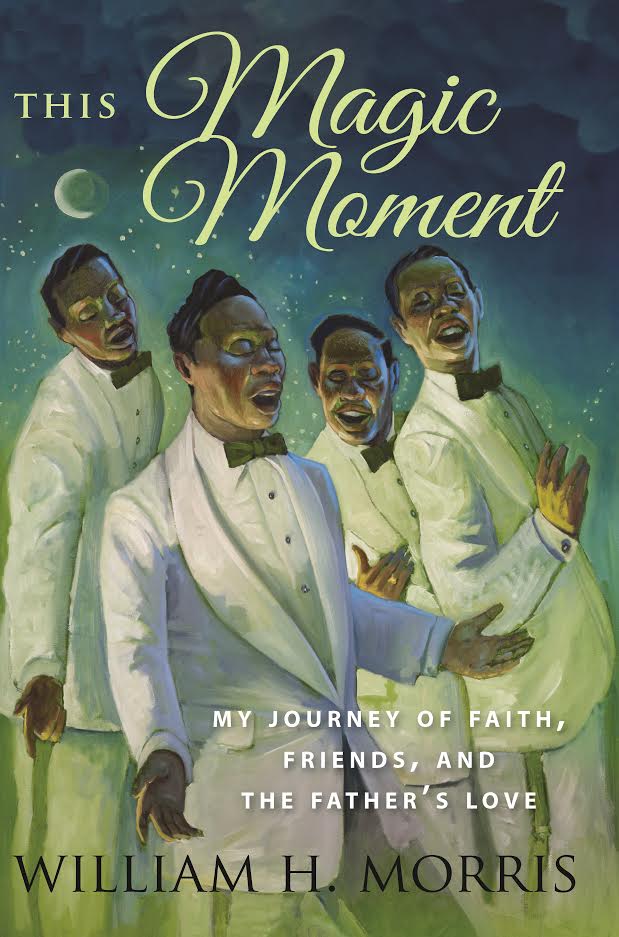

William H. (Bill) Morris would tell you that he has had more than his share of “magic moments’ in his lifetime, and he shares many details of his close-knit friendships with some of the greatest musicians of the R & B, Rock and Roll and Doo-Wop era of the ‘50s and ‘60s in his heartfelt memoir, This Magic Moment: My Journey of Faith, Friends, and the Father’s Love.

William H. (Bill) Morris would tell you that he has had more than his share of “magic moments’ in his lifetime, and he shares many details of his close-knit friendships with some of the greatest musicians of the R & B, Rock and Roll and Doo-Wop era of the ‘50s and ‘60s in his heartfelt memoir, This Magic Moment: My Journey of Faith, Friends, and the Father’s Love.

Growing up in Jackson during this period, Morris became especially fascinated with the popular melodies and harmonies of the doo-wop musicians–and though he would go on to establish a highly successful insurance firm, he never forgot his fondness for the music of that period.

William Morris

Through a series of providential circumstances, Morris would go on to befriend several of the most famous among those musical legends, including members of the Moonglows, the Drifters, and other groups. These deep lifelong relationships would see him offer aid and encouragement to musicians whose careers had waned, including at least one who found his health, finances, and hope declining.

Through it all, Morris steadfastly credits his strong faith in God for allowing him the opportunities to forge “enduring bonds that would last beyond their lifetimes,” creating examples to inspire others.

A lifelong resident of Jackson, Morris and his wife Camille have been married 47 years and their family includes two daughters and five grandchildren. He has also authored a coffee table book entitled Ole Miss at Oxford: A Part of Our Heart and Soul.

In the introduction of your book, This Magic Moment, you tell readers that you have always had “a deep and abiding bond with music”–one that led you to seriously consider music promotion as a career. Why did you decide to pursue a career in insurance instead?

My father knew college would be more valuable to me if I had “skin in the game,” as in paying for half of the cost myself. The way I was able to earn that money was by hosting and promoting dances around Jackson, which I loved doing. Fourteen of those dances were big successes. The one that wasn’t made me realize that music promotion was an unpredictable career and would not give the financial stability I wanted to support an eventual wife and family.

My father was a successful insurance executive who was devoted to the welfare of his clients, and they loved him for it. I decided to follow his path, which proved to be the right decision. I am proud and grateful for the success I have had with the firm, and as I discovered, it was possible for me to also pursue my passions for music, photography, and writing at the same time.

You grew up during a time when popular music changed from listening to Guy Lombardo on the radio to rock and roll and “doo-wop” songs on 45 rpm records. How did you come to form lasting relationships with singers who were among the most famous in the country during the 1950s and 1960s?

I fell in love with R&B/doo-wop from the first time I heard it in high school. The rich harmonies and the passionate delivery of the music was different from anything I had heard before. I began listening to WOKJ in Jackson, WLAC in Nashville, and WDIA in Memphis, which were some of the only stations accessible in the area that played the African American sounds of rhythm and blues and doo-wop. I would also go to Capital Music in downtown Jackson to sample the newest 45s. This touched my soul, and I could not get enough of it.

I was able to meet some of my musical heroes while promoting dances and later booking groups for my fraternity in college. However, the relationships were formed much later in life as a result of my friendship with Prentiss Barnes, the original bass singer of The Moonglows. He invited me to be his guest at major musical events that gave me the opportunity to meet and come to know a virtual who’s who of rock and roll, rhythm and blues, and doo-wop musicians. It was my friendship with Prentiss that led to my long and dear friendship with Bill Pinkney of the Original Drifters and later Harvey Fuqua and Rufus McKay. I spoke and sang at all four of their funerals. They became like brothers to me.

You state that your book is “a love story of deep friendship, given from above.” How did your relationship with Prentiss Barnes begin, and how did it develop through the years?

The Moonglows were one of my favorite groups. While on a business trip to Washington D.C. in 1980, I attended a performance of The Moonglows. I took the opportunity to meet them during a break and before long we were singing some of their hits. Bobby Lester heard something in my voice that prompted him to insist I sing the lead on a song with them in the next set. I never considered myself to be a singer and had never had a mic in my hand. Although I was reluctant, singing with some of my musical heroes was one of the biggest thrills of my life. It also played a big role in my eventual relationship with Prentiss.

Almost exactly a year from this event, I picked up the Clarion-Ledger and saw the front-page story about Prentiss Barnes, who was now living in Jackson in complete despair. He was broken in every way–physically, financially, spiritually. The Holy Spirit made it clear to me that I was to reach out and help him. When I first tried, Prentiss was very unreceptive and skeptical until I told him about singing with The Moonglows in Washington.

We were able to help get him the help he needed, and our friendship grew over three decades to be one of the most important relationships of my life. He included me in all the big moments in his life–including The Moonglows’ induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Several years later he gave me his award, saying that it would have never happened if I had not come into his life. I cannot express how gratifying it was to see him go from someone with one foot in the grave who was hopeless to having him know that he was appreciated and loved by so many.

Would you briefly share some of the music-related highlights that are part of the journey you write about in your book?

- Forming Hallelujah Productions and producing two gospel CDs with the Original Drifters in 1995.

- Serving as chairman of a 2002 benefit at the Country Club of Jackson in honor of Prentiss Barnes and establishing a fund for musicians in need. Morgan Freeman was the honorary chairman.

- Performing with The Moonglows at Boston Symphony Hall as part of their Doo Wop Hall of Fame induction in 2005.

Please tell me why you wrote this book, who should read it, and why you titled it This Magic Moment.

It is my intent to bless and inspire people. By acting on the urgings of the Holy Spirit, my life was enhanced beyond measure and in ways I could have never imagined. I hope people will be encouraged to trust and obey our Heavenly Father when he speaks to you.

The other important message I want to share is that people from different backgrounds, circumstances, political beliefs, etc. can find what they have in common and build meaningful relationships and all will be blessed. We all have far more in common than we have differences.

This Magic Moment is not only the name of one of the Drifters’ most famous songs, it is a metaphor for life. We have many “magic moments” in our lives that lead to other “magic moments” if we take the time to recognize them. Sometimes it is only when we look back that we realize how everything magically worked together.

William Morris will be at Lemuria on Friday, November 29, from 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. to sign copies of This Magic Moment.

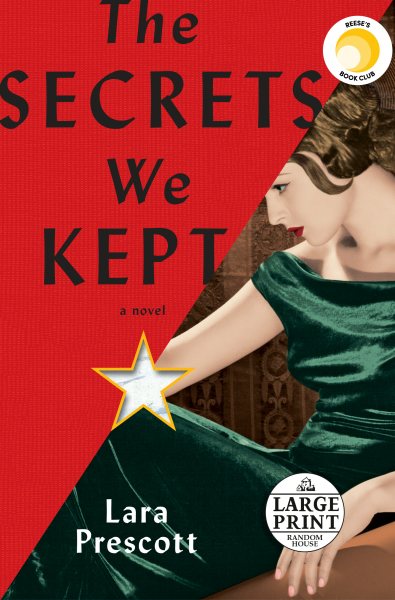

Lara Prescott’s fictional account of three young women employed in the CIA’s typing pool who rise to the upper echelons of espionage during the 1950s Cold War is based on the true story of the agency’s undercover plan to smuggle copies of Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago into the USSR.

Lara Prescott’s fictional account of three young women employed in the CIA’s typing pool who rise to the upper echelons of espionage during the 1950s Cold War is based on the true story of the agency’s undercover plan to smuggle copies of Boris Pasternak’s Dr. Zhivago into the USSR.

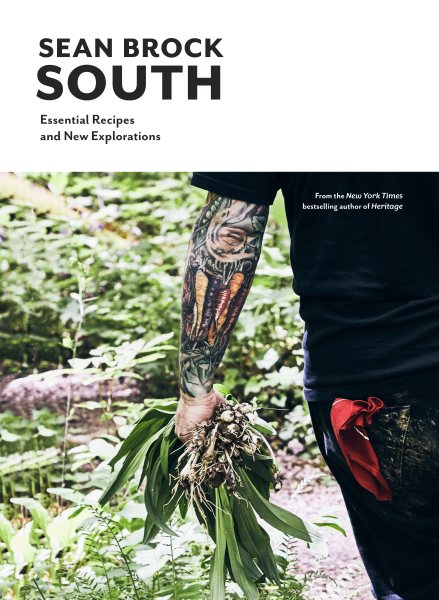

Sean Brock, the James Beard Award-winning author of Heritage follows up his nationally acclaimed debut book with a decidedly enthusiastic probe into the nurturing and connecting qualities of his favorite cuisine with

Sean Brock, the James Beard Award-winning author of Heritage follows up his nationally acclaimed debut book with a decidedly enthusiastic probe into the nurturing and connecting qualities of his favorite cuisine with

In his second inaugural address, delivered in March 1865, Abraham Lincoln expressed his hope that “this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away” but also allowed that it might yet be God’s will that “every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword.”

In his second inaugural address, delivered in March 1865, Abraham Lincoln expressed his hope that “this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away” but also allowed that it might yet be God’s will that “every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword.” After decades of those-who-know-don’t-need-to-ask operation catering to locals in search of a Thursday evening respite, the establishment rose to prominence as white photographers and journalists enthralled by its authenticity brought news of its existence to their audiences, turning it into a must-see site for blues tourists traveling the Mississippi Delta.

After decades of those-who-know-don’t-need-to-ask operation catering to locals in search of a Thursday evening respite, the establishment rose to prominence as white photographers and journalists enthralled by its authenticity brought news of its existence to their audiences, turning it into a must-see site for blues tourists traveling the Mississippi Delta. On May 1, 1863, Ulysses S. Grant’s Union Army of the Tennessee crossed the Mississippi River on a flotilla of steamboats, gunboats and barges and landed on Mississippi soil at Bruinsburg. It was the largest amphibious landing by an American army in history and would remain so until World War II.

On May 1, 1863, Ulysses S. Grant’s Union Army of the Tennessee crossed the Mississippi River on a flotilla of steamboats, gunboats and barges and landed on Mississippi soil at Bruinsburg. It was the largest amphibious landing by an American army in history and would remain so until World War II.

It is the global projection of this image, as imperfect as it may be in actuality, that has long been a part of the lore and lure of the United States of America. It is the mirage that entices thousands upon thousands of people to leave their troubled homelands and, sometimes, risk their lives to come to “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” where they are free to live their lives as they see fit, worship the God of their choice, and consume as much as their wallet will allow.

It is the global projection of this image, as imperfect as it may be in actuality, that has long been a part of the lore and lure of the United States of America. It is the mirage that entices thousands upon thousands of people to leave their troubled homelands and, sometimes, risk their lives to come to “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” where they are free to live their lives as they see fit, worship the God of their choice, and consume as much as their wallet will allow.