Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (October 6)

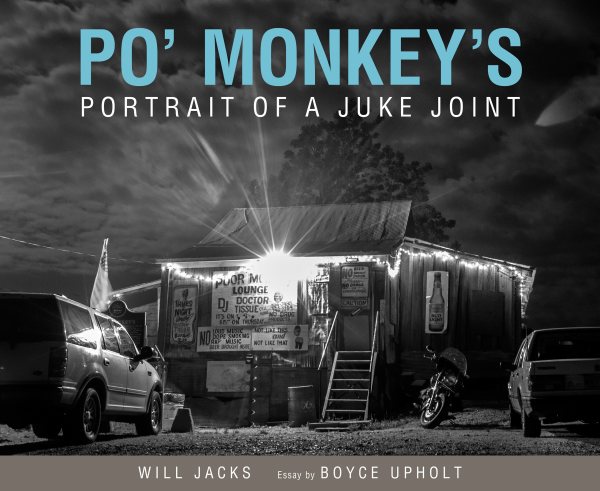

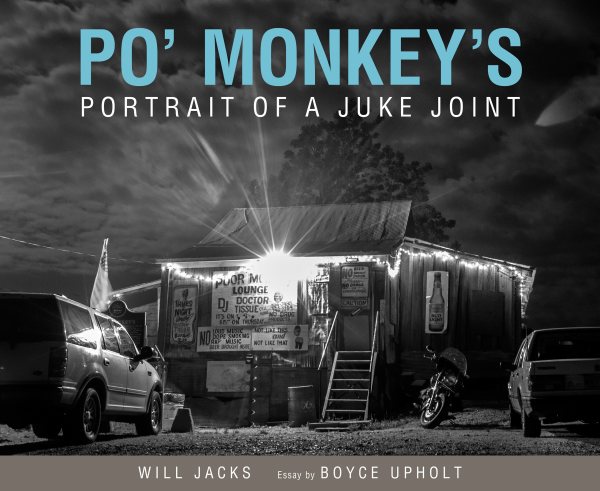

Mississippi Delta photographer and documentarian Will Jacks celebrates the life and times of the late Willie Seaberry, owner of Po’ Monkey’s blues house in Merigold for more than 50 years, in Po’ Monkey’s: Portrait of a Juke Joint (University Press of Mississippi).

Mississippi Delta photographer and documentarian Will Jacks celebrates the life and times of the late Willie Seaberry, owner of Po’ Monkey’s blues house in Merigold for more than 50 years, in Po’ Monkey’s: Portrait of a Juke Joint (University Press of Mississippi).

Jacks extols the history of the night club that closed with Seaberry’s death in 2016, while pondering the future of the deteriorating hand-built tenant house that was once a blues hot spot.

With more than 70 black-and-white photos and an introduction by award-winning writer Boyce Upholt, Jacks highlights the cultural significance and the need to honor it with a historical record.

Among his many talents and skills, Jacks is also a curator and storyteller, and he teaches photography and documentary classes at Delta State University.

What was it about Po’ Monkey’s juke joint in Merigold that made it such a must-see stop for Blues-loving tourists and locals?

Willie Seaberry

It was Willie Seaberry. The locals definitely came over the years because of him and the welcoming environment he created. And then the locals became the glue that made Po’ Monkey’s different from almost every other space frequented by blues tourists. The mix of tourists and locals created an amazing atmosphere of sharing, and when that atmosphere was combined with the visual drama of the structure and its location in the middle of a farm, well, there was a perfect recipe for an incredibly unique experience–and a good time.

You say in the book that Willie Seaberry knew you (a regular at this establishment for a decade), but you don’t think he knew your name. Tell me about your relationship with him.

Will Jacks

Willie was never great with names, but he had an ability to hide that and make everyone feel as if he were their best friend. I saw him do this over and over and over again. Someone would enter the club–usually a tourist that made yearly trips to the Delta–and give him a warm greeting as if they were family. Willie would reciprocate, and the guest would feel as if it was just a matter of time before Willie came to visit at their home. It wasn’t that Willie was disingenuous–he loved sharing a good time with his guests–it’s just that so many people came in and out of his life that it must have been impossible for him to keep track of all those names and faces.

I was no different. Even though I visited most Thursday nights, I didn’t see Willie as regularly outside of that environment as his closest friends and family. So, I doubt he ever knew my name. I don’t recall a single time that he called me by it, but I could tell from our interactions over the years that he knew who I was. He just didn’t know my name.

He would often ask me to bring him posters I’d made. He liked the portraits I’d used for them. So, I would, and he would give them away and sometimes sell them. He gave me photo books that others had given him over the years. He didn’t much care for them but knew I would. So, he shared them with me. He liked to tease me the way a favorite uncle does. He sometimes would vent to me. He would buy me beer and let me into the club for free. I drove his truck a few times to run errands for him (and for me). I spoke at his funeral.

But we were never best friends. To insinuate that on my part would be disingenuous. I was still one of the many photographers and filmmakers that asked for his time. That was always the crux of our relationship. It just happened that I was the one documentarian that was out there the most, and the one who lived just a few miles away. Because of this, we would see each other outside the confines of his weekly party, and that helped our relationship go further than subject/photographer but not as far as close friend and family.

In what state of repair is Po’ Monkey’s at this time, and what, if any, plans are taking shape for its future?

The structure is still standing, but it’s seeing some decline due to lack of use. The exterior signs have been removed as they were sold at auction last year along with many of his belongings and interior decor.

As for future plans, that’s not my decision to make. There are others in charge of those decisions, and solutions are complicated for a myriad of reasons. I am in touch with many of those stakeholders, but it’s not my place to share whatever plans are being considered, and even then, I don’t know what all is being specifically discussed.

I can say, though, with confidence that all involved are concerned primarily with appropriately honoring what Willie Seaberry built. That seems simple enough on the surface, but when you dig into the specifics it’s much more challenging. Cultural preservation is a tricky thing. I feel certain that something will happen to honor Willie. As to what that is, we’ll all just have to be patient and trusting to until that answer emerges. And perhaps even more so, we will all need to be ready to pitch in to help when and if that time presents itself, as the best preservation is one that is led by community.

Tell me about the images in your “Portrait of a Juke Joint,” and the way you decided to present them in this book–black and white, with no identifications of people or their behaviors in the shots. Over what period were they taken, and how long did it take to produce this book?

I chose black and white specifically because I wanted the people to be the focus–I didn’t want the viewer becoming overly seduced by the colorful space. The structure was compelling, yes, but it was the people, and specifically the locals, that made it magical.

There are to titles because I didn’t want anything to lead the viewer as they look through the photos. I want the viewer to have room to imagine what has occurred before and after the image they are pondering. Sometimes with captions, the words create too much context. I felt there was enough context already in the photos, and anything more would risk the work becoming didactic, which I hope to avoid.

Ultimately, what do you hope to accomplish through this book?

I hope to show that Po’ Monkey’s was a complex place that was more than just a tourist spot. It was crafted from a complex history and became significant both despite that history and because of it.

We will never see another Po’ Monkey’s again, but we will see spaces all around us that become culturally significant without intending to be. Knowing that this is the case, how can we as communities do better jobs of recognizing and supporting those people, moments, and places?

I hope this book will help us as a state, and in particular those in positions of power, consider what we’ve done well but also, and perhaps more important, what we haven’t done well as we have consciously crafted an economy built around a very complex and often painful history.

I hope this book will help give a deeper understanding to just how difficult historic preservation can be.

And finally, I hope this book will help us ask the right questions so we can get to the right answers as to how we can share with future generations the lessons taught by Willie Seaberry.

Will Jacks will be at Lemuria on Tuesday, October 22, at 5:00 to sign and discuss Po’ Monkey’s: Portrait of a Juke Joint.

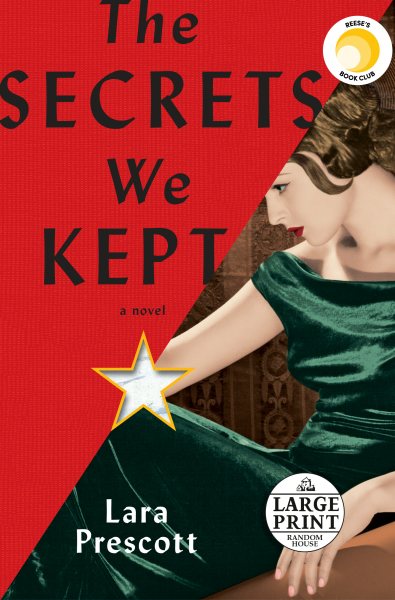

The Secrets We Kept is a debut novel by Lara Prescott based on the true events surrounding the 1957 publication of Dr. Zhivago, a 20th century literary masterpiece combining a sweeping love story with intrigue, political hardship, and tragedy, set between the Russian Revolution and WWII. One of the greatest love stories ever written, it was made into the haunting film featuring Julie Christie and Omar Sharif. Boris Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for it, which he was made to turn down by an embarrassed and outraged KGB. It was banned reading there until 1988. But if you haven’t read it, now you’re up to speed, and you can read The Secrets We Kept!

The Secrets We Kept is a debut novel by Lara Prescott based on the true events surrounding the 1957 publication of Dr. Zhivago, a 20th century literary masterpiece combining a sweeping love story with intrigue, political hardship, and tragedy, set between the Russian Revolution and WWII. One of the greatest love stories ever written, it was made into the haunting film featuring Julie Christie and Omar Sharif. Boris Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for it, which he was made to turn down by an embarrassed and outraged KGB. It was banned reading there until 1988. But if you haven’t read it, now you’re up to speed, and you can read The Secrets We Kept!

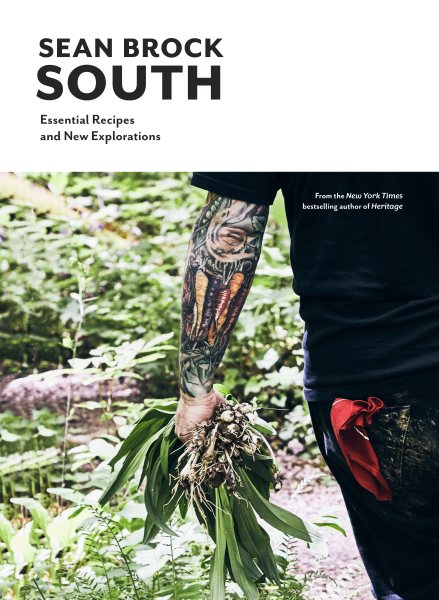

Sean Brock, the James Beard Award-winning author of Heritage follows up his nationally acclaimed debut book with a decidedly enthusiastic probe into the nurturing and connecting qualities of his favorite cuisine with

Sean Brock, the James Beard Award-winning author of Heritage follows up his nationally acclaimed debut book with a decidedly enthusiastic probe into the nurturing and connecting qualities of his favorite cuisine with

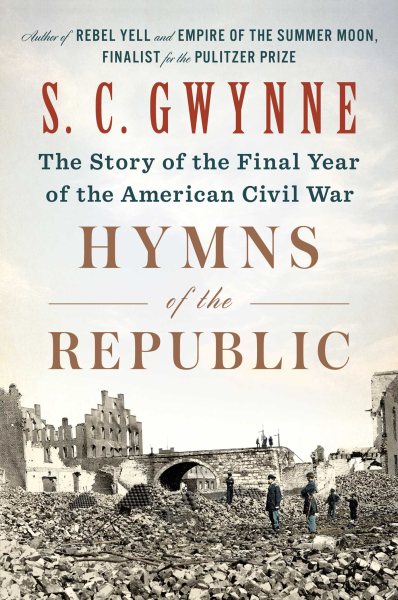

If you haven’t given much thought to the American Civil War lately, bestselling author and Pulitzer Prize finalist S. C Gwynne offers some compelling thoughts on the country’s current state of division as he examines–in depth–the fourth and final year of the War Between the States.

If you haven’t given much thought to the American Civil War lately, bestselling author and Pulitzer Prize finalist S. C Gwynne offers some compelling thoughts on the country’s current state of division as he examines–in depth–the fourth and final year of the War Between the States.

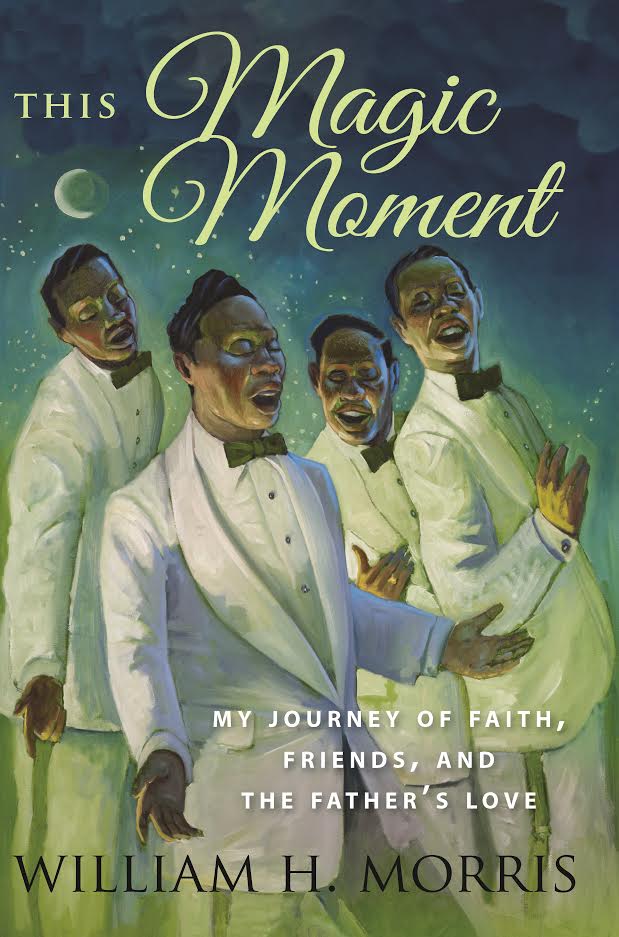

Some people make their own luck. Others have never met a stranger. In the case of lifelong Jacksonian Bill Morris, these notions work in tandem. As the founder of the William Morris Group, Bill has made a name for himself nationally in the insurance world. However in his memoir,

Some people make their own luck. Others have never met a stranger. In the case of lifelong Jacksonian Bill Morris, these notions work in tandem. As the founder of the William Morris Group, Bill has made a name for himself nationally in the insurance world. However in his memoir,  It is the global projection of this image, as imperfect as it may be in actuality, that has long been a part of the lore and lure of the United States of America. It is the mirage that entices thousands upon thousands of people to leave their troubled homelands and, sometimes, risk their lives to come to “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” where they are free to live their lives as they see fit, worship the God of their choice, and consume as much as their wallet will allow.

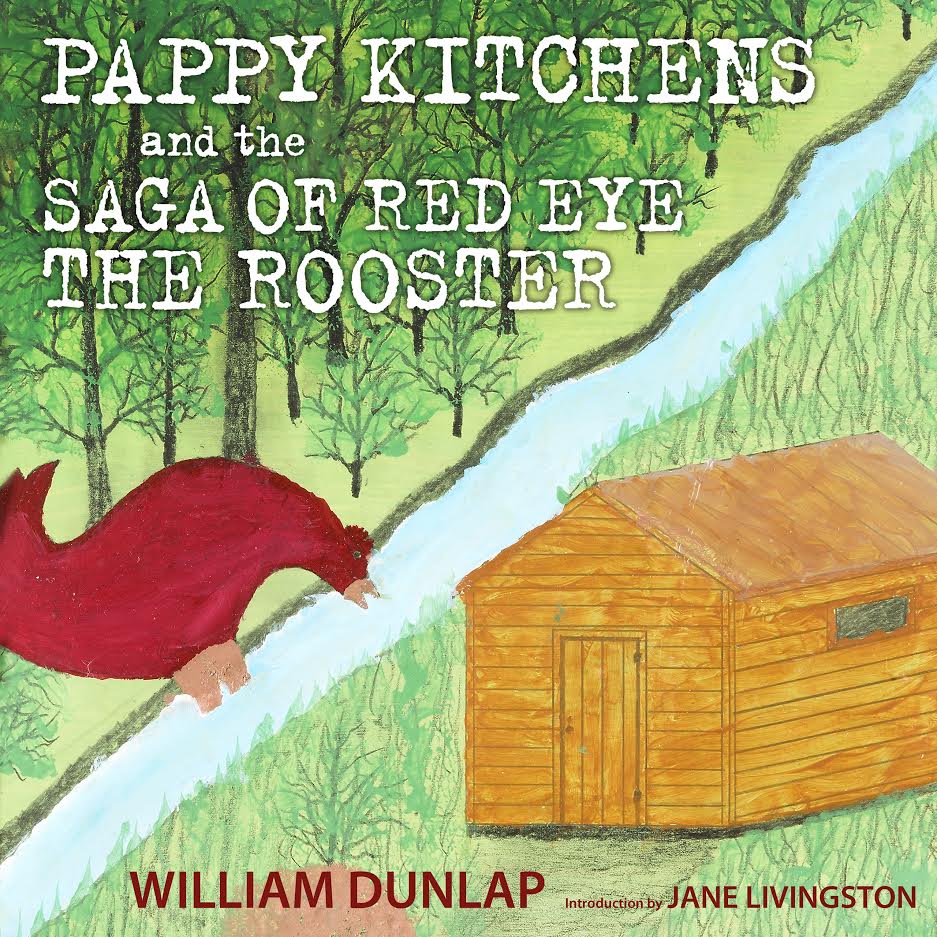

It is the global projection of this image, as imperfect as it may be in actuality, that has long been a part of the lore and lure of the United States of America. It is the mirage that entices thousands upon thousands of people to leave their troubled homelands and, sometimes, risk their lives to come to “the land of the free and the home of the brave,” where they are free to live their lives as they see fit, worship the God of their choice, and consume as much as their wallet will allow. O.W. “Pappy” Kitchens was a distinctive Mississippi character. He was a building contractor and house mover, as well as an accomplished storyteller, who, after he sold his business and retired, discovered that he was an artist.

O.W. “Pappy” Kitchens was a distinctive Mississippi character. He was a building contractor and house mover, as well as an accomplished storyteller, who, after he sold his business and retired, discovered that he was an artist. Mississippi Delta photographer and documentarian Will Jacks celebrates the life and times of the late Willie Seaberry, owner of Po’ Monkey’s blues house in Merigold for more than 50 years, in

Mississippi Delta photographer and documentarian Will Jacks celebrates the life and times of the late Willie Seaberry, owner of Po’ Monkey’s blues house in Merigold for more than 50 years, in

Brittney Morris’s hot debut novel presents a relevant and hard-hitting YA tale of a black teen game developer–17-year-old Kiera Johnson–who created the secret multiplayer role-playing game called Slay.

Brittney Morris’s hot debut novel presents a relevant and hard-hitting YA tale of a black teen game developer–17-year-old Kiera Johnson–who created the secret multiplayer role-playing game called Slay.

A self-acknowledged “steady diet of horror fiction and monster movies” as he was growing up has, for Arlinton, Texas, native Shaun Hamill, resulted in a debut novel that makes Halloween look like a day in the park.

A self-acknowledged “steady diet of horror fiction and monster movies” as he was growing up has, for Arlinton, Texas, native Shaun Hamill, resulted in a debut novel that makes Halloween look like a day in the park.