Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (March 25)

Memphis’s Grammy and Emmy award-winning author and filmmaker Robert Gordon highlights his city’s lesser known artists who he proudly emphasizes brought “something different” to the Memphis music scene through their authenticity and uncommon styles.

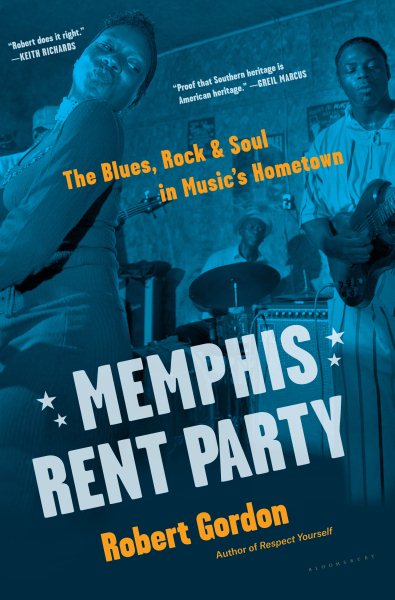

Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music’s Hometown is a collection of 20 profiles and stories composed throughout his career of more than four decades of passionate writing about the music of his beloved Memphis.

Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music’s Hometown is a collection of 20 profiles and stories composed throughout his career of more than four decades of passionate writing about the music of his beloved Memphis.

Gordon’s previous books, all about the American South, and its music, art, and politics, include It Came from Memphis, Can’t Be Satisfied: The Life and Times of Muddy Waters, and Respect Yourself. His work on Keep an Eye on the Sky was selected as a Grammy winner.

His film work includes the documentaries Johnny Cash’s America and William Eggleston’s Stranded in Canton. His Best of Enemies was shortlisted for an Oscar and won an Emmy.

Born and raised in Memphis, he still calls the city his home and touts: “I drink my whiskey neat.”

Memphis Rent Party: The Blues, Rock & Soul in Music’s Hometown is a collection of essays about Memphis artists and producers who you believed best convey the spirit of Memphis. What exactly is a rent party?

When I was studying the Harlem Renaissance about 40 years ago, I learned about rent parties, where people who couldn’t make the rent would throw a party, charge admission, sell booze, and get by another month. I loved the idea of friends helping friends by having fun together. And it occurred to me then, way back, that “Rent Party” would be a great name for a collection of stories. The work is already done, you’re throwing a few stories together to get a book deal. But it turned out, when I had the opportunity, I took it much further, interconnecting the stories with new text, digging up old unpublishable pieces, and generally putting in a full book’s effort. The result, Memphis Rent Party, is a lot of fun–like a rent party should be, but it was a lot more work than I anticipated.

And by “unpublishable” I mean, for example, I wrote a piece about the mother of jazz greats Phineas and Calvin Newborn. It’s hard enough to get a piece of either of them published, but on their mom? No way. So, I wrote that for myself, put it in a drawer, and moved on. I dug it out for this, because I could finally get it out.

How did you choose these particular stories?

I didn’t set out with a particular goal, but one formed as I got into the material. I saw a unifying theme, a sense of individuality that is epitomized by Sam Phillips and by what Sam sought.

Elvis would have been singing Perry Como-style ballads and become a forgotten minor entertainer if it hadn’t been for Sam. Sam affirmed for him that the wild streak in him, the uniquely Elvis part of Elvis, was OK to reveal, was something to pursue.

That’s the spirit that unifies the book. These are individuals who have created their own characters, forged new paths. These are not followers, they’re people cutting their own path–and very often, that path becomes a major highway that lots of people follow.

What was it that attracted you to this music at a young age–music that was so unlike your growing up years, at a time when you described your teenage self as a “rebellious outsider” and as a “seeker.”

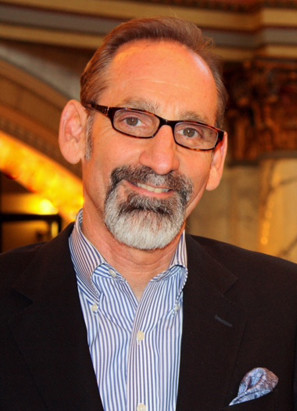

Robert Gordon

This music hit harder and deeper than anything I’d ever heard. It didn’t say, “I’m hear to rock you.” It didn’t say, “Let’s be entertained.” Though all music is just a combination of notes, the delivery of this music felt different. It had history, meaning, and heft. I wanted to understand it in a way that Molly Hachet, Kiss, and later, Boston–pop groups of the time–offered no deeper meanings.

One of your earliest (if not your first) face-to-face encounters with a music legend was with Furry Lewis, a solo blues artist from Memphis who was “about 80 years old,” when he opened for a Rolling Stones concert in Memphis in 1975. What “bonded” you with Furry almost immediately?

I think the bond was me to Furry, and Furry–initially, anyway–saw me as just another curious person knocking on his door and shelling out a couple bucks. But he did soon recognize me, because I returned often. His duplex was a place different from anyplace I knew, and being there, being with him, observing his environment and his friends–it all posed many questions to me, made me curious, opened up avenues to explore.

You began your writing career in the mid-80s when you began feeding now-defunct magazines stories about musical talents that weren’t first tier stars, but those who offered listeners “something different.” You say that theirs was a “shadow influence.” Describe what that means.

The most clear sense of shadow influence is that many pop hits were built on, of simply copies of, previous blues, soul, or other songs. The Stones cut Robert Johnson songs, and Fred McDowell and the Rev. Robert Wilkins. The Stones were influenced by artists that many of their fans would never realize. All of pop music was. That day in 1975, when I heard Furry open for the Stones, he was immediately more interesting than they were. Nowhere near as huge–in sound, popularity, onslaught, or in any way–but imbued with more than the Stones could hope for. That was in part because he was a living relic of a previous time, but also because I think fewer notes say way more than many notes. In music, in cinema, in writing, it’s about the space, the air, the room you leave, nor the room you take up.

In the book’s preface, you predict that 100 years from now, the music of these marginalized artists “will still be popularly unpopular–will still be hip.” Explain why you believe that.

History has shown it to be. Popular music doesn’t remain popular. It catches a sense of time, then moves on. The Romantics or the Cars scream “1980s,” but they don’t have much power other than that now. They evoke a time. These marginalized artists also evoke a time, but more than that, they tell a story. A personal story, a universal story, a news story of the day–their songs and lives and art.

OK, I’m interrupting myself, because here’s the key: individuality. The credo of godhead Sam Phillips. “Give me something different.” Pop artists capture their times, sound like anyone in those times could. These more marginalized artist sound only like themselves. Individuality lives on, popularity fades with the times.

What is the book about the overall message of Memphis Rent Party?

It’s about flouting the trends to become a unique individual. It’s the Sam Phillips mindset applied to people Sam never encountered. He encountered Howlin’ Wolf and B.B. King and Jerry Lee and Johnny Cash and Elvis, and for all of them, he shifted them away from their pop dreams to finding their own artist.

By expressing themselves, these people created new paths, new styles, new trends. And the same is true about the people in the book. They’re all sui generis–they created their own thing. Sam once said, Nashville has a follower’s mentality. That’s why he stayed in Memphis.

An accompanying LP will be released by Fat Possum Records, with the artists on the soundtrack among those featured in the book. What kind of music will the soundtrack have?

This soundtrack, like the Memphis and Mississippi artists it covers, is all over the place. There’s blues, jazz, country, rock and roll. There’s everything but gospel, but there’s definitely the gospel of rock and roll.

Do you have potential projects that you want readers to know about?

I work on a lot of projects at once. In this kind of work, you have to. I’m hoping to announce a new feature doc, music-oriented, real soon. I’ve got several feature docs in the works. I’m shooting in North Carolina for two weeks in April for the second half of a documentary with a UK artist, Bill Drummond. We shot the first half in Kolkata, India. He’ll do his thing in the two places and, I think, the different reactions he gets will reveal a lot about the world we live in today.

Robert Gordon will be at Lemuria on Monday, March 26, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and read from Memphis Rent Party.

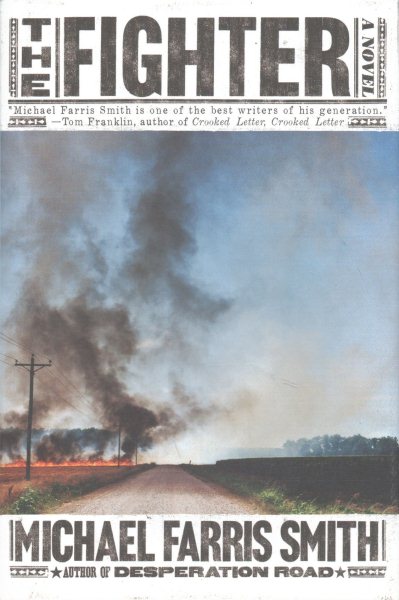

You win the prize for my favorite question about The Fighter so far. Maybe it’s because we are all fighters. We all have made mistakes, we have hurt people who love us, we have done things we regret and knew we were going to regret it as we were doing it, and we all fight to try and fix what we’ve done after we’ve broken it.

You win the prize for my favorite question about The Fighter so far. Maybe it’s because we are all fighters. We all have made mistakes, we have hurt people who love us, we have done things we regret and knew we were going to regret it as we were doing it, and we all fight to try and fix what we’ve done after we’ve broken it. Those are the questions readers will be asking themselves after the final page is turned in

Those are the questions readers will be asking themselves after the final page is turned in

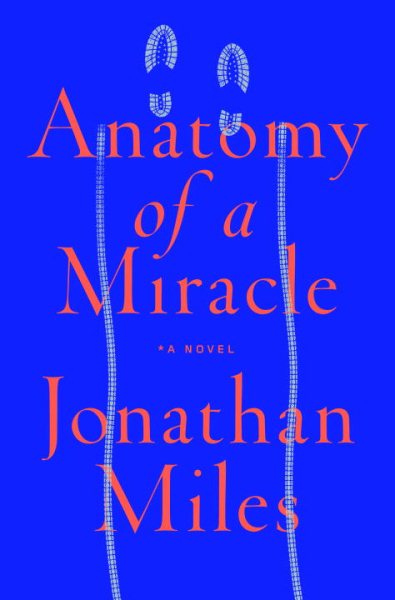

It began with a simple what-if question: What if a miraculous-seeming event happened today, in America? An event that defied all explanation? What would it look like–in the press, on social media? What kinds of cultural fault lines would it cause to rumble? And what effects–aside from the physical recovery–would this event have on the lives of those it touched? It was a spiral of questions.

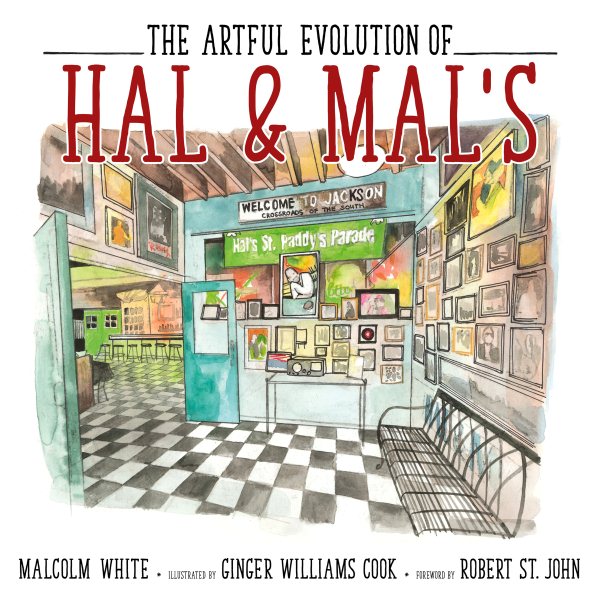

It began with a simple what-if question: What if a miraculous-seeming event happened today, in America? An event that defied all explanation? What would it look like–in the press, on social media? What kinds of cultural fault lines would it cause to rumble? And what effects–aside from the physical recovery–would this event have on the lives of those it touched? It was a spiral of questions. White’s salute to the more than three decades of success at the iconic establishment he and big brother Hal opened in 1985 is

White’s salute to the more than three decades of success at the iconic establishment he and big brother Hal opened in 1985 is

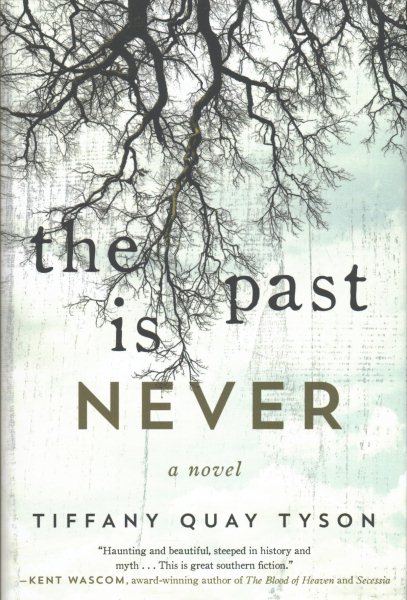

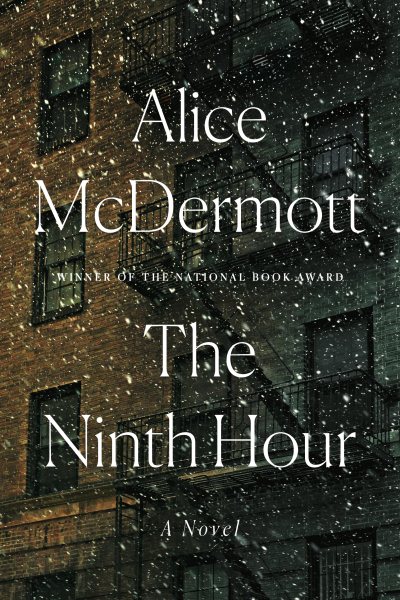

The book begins with the story of a pregnant widow of a suicide victim whose newborn daughter is raised by the nuns of the Little Nursing Sisters of the Sick Poor. The movingly complex, lovingly crafted story of a family continues through another generation.

The book begins with the story of a pregnant widow of a suicide victim whose newborn daughter is raised by the nuns of the Little Nursing Sisters of the Sick Poor. The movingly complex, lovingly crafted story of a family continues through another generation. Their new book,

Their new book,