by Andrew Hedglin

“Travis McGee’s still in Cedar Key—

That’s what ol’ John MacDonald said.

My rendezvous’s so long overdue

With all of the things I’ve sung and I’ve read.”

–Jimmy Buffett, “Incommunicado”

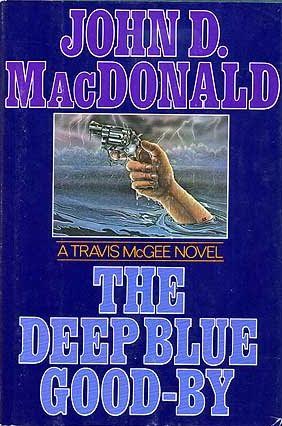

I read my first Travis McGee book in 2006, after my freshman year of college. I think I stole the paperback from my brother, but it was my father with whom I shared the rest of the 21 book series over a period of four years. He started reading them as the later ones first came out, but he’s a little young to have caught 1962’s The Deep Blue Good-by, the series debut by noted pulp crime writer John D. MacDonald.

I read my first Travis McGee book in 2006, after my freshman year of college. I think I stole the paperback from my brother, but it was my father with whom I shared the rest of the 21 book series over a period of four years. He started reading them as the later ones first came out, but he’s a little young to have caught 1962’s The Deep Blue Good-by, the series debut by noted pulp crime writer John D. MacDonald.

I say “noted” because it’s not just my family who respects MacDonald. He has influenced mystery writers from Carl Hiaasen to Lee Child, both of whom have written introductions for his books and received praise from other writers such as Stephen King, Dean Koontz, Robert B. Parker, and Ed McBain.

Personally, I’ve always had a soft spot for continuing characters in crime fiction series, starting with Lawrence Block’s burglar Bernie Rhodenbarr and Rick Riordan’s tequila-drinking, tai chi-fighting English professor P.I. Tres Nevarre and continuing currently to Greg Iles’ Natchez crusader Penn Cage. Each of those series has such a specific sense of character and place. The protagonists are really law enforcement professionals, which sometimes takes the human element out of most crime fiction for my taste.

Travis McGee is a self-styled “salvage consultant” who retrieves precious commodities for people with few legal resources and splits the profits 50-50 after expenses. This debut novel in the series, with almost no origin story to weigh it down, moves quickly as McGee matches wits with oversexed psychopath Junior Allen. He’s trying to recover gemstones smuggled home from World War II by the father of Cathy Kerr, a local showgirl and single mother.

The Travis McGee novels (which can all be identified by the colors in their title, all the way to 1985’s elegiac Lonely Silver Rain) have tightly-constructed and entertaining plots, but it’s the little things that stick with you after you read them: McGee’s philosophical ruminations, proto-environmentalism, and general unease with adapting to modern life (even 50 years ago). The richly detailed settings of 1960s Fort Lauderdale, especially Bahia Mar, where McGee’s houseboat, The Busted Flush, is parked right next to the Alabama Tiger’s Perpetual Floating House Party. And, even though he is strangely missing from The Deep Blue Good-by, the person who outlasts any of McGee’s various lovers is Meyer, the bearded economist living about his yacht the John Maynard Keynes, who frequently plays Watson to McGee’s Sherlock.

The Travis McGee novels (which can all be identified by the colors in their title, all the way to 1985’s elegiac Lonely Silver Rain) have tightly-constructed and entertaining plots, but it’s the little things that stick with you after you read them: McGee’s philosophical ruminations, proto-environmentalism, and general unease with adapting to modern life (even 50 years ago). The richly detailed settings of 1960s Fort Lauderdale, especially Bahia Mar, where McGee’s houseboat, The Busted Flush, is parked right next to the Alabama Tiger’s Perpetual Floating House Party. And, even though he is strangely missing from The Deep Blue Good-by, the person who outlasts any of McGee’s various lovers is Meyer, the bearded economist living about his yacht the John Maynard Keynes, who frequently plays Watson to McGee’s Sherlock.

Although firmly rooted in their eras, the novels hold-up as timeless summer beach reads (or books to read when dreaming of beaches). Travis McGee is part-James Bond (as 60s action-hero and serial monogamist), part-Jimmy Buffett type (as beach bum and underrated philosopher-poet) who always manages to feel unique to himself. This summer, I recommend revisiting his old adventures, starting with one of his toughest opponents in The Deep Blue Good-by.

Johnny Anonymous, a white offensive lineman in the NFL who wishes to remain, well…anonymous, opens his book

Johnny Anonymous, a white offensive lineman in the NFL who wishes to remain, well…anonymous, opens his book

Graciela is an eighteen year-old from a tiny town called Delores Hidalgo, before she finds herself in the care of an abortion doctor named Doc Ebersole on the South Presa Strip in San Antonio, Texas. Doc has been haunted by the ghost of

Graciela is an eighteen year-old from a tiny town called Delores Hidalgo, before she finds herself in the care of an abortion doctor named Doc Ebersole on the South Presa Strip in San Antonio, Texas. Doc has been haunted by the ghost of  Lupe, however, casts a long shadow in the other direction. The 13 year-old younger sister to the protagonist 14 year-old Juan Diego, she hails from the city dump just outside of Oaxaca. Due to webbing in her vocal chords, her voice is unintelligible to everybody but Juan Diego, but must translate for her. She can read minds and—perhaps—predict the future. She is opinionated, salty, and later on, quite vulgar. She takes orders from no one, but like Graciela, she is a born protector. She and her brother are named after Virgin of Guadalupe, a vision of Mary who appeared in Mexico in the 1500s, and the Aztec man who discovered her. She is capable of great faith, but demands results.

Lupe, however, casts a long shadow in the other direction. The 13 year-old younger sister to the protagonist 14 year-old Juan Diego, she hails from the city dump just outside of Oaxaca. Due to webbing in her vocal chords, her voice is unintelligible to everybody but Juan Diego, but must translate for her. She can read minds and—perhaps—predict the future. She is opinionated, salty, and later on, quite vulgar. She takes orders from no one, but like Graciela, she is a born protector. She and her brother are named after Virgin of Guadalupe, a vision of Mary who appeared in Mexico in the 1500s, and the Aztec man who discovered her. She is capable of great faith, but demands results.

fully convinced, by the Ole Miss iconography on their respective covers. I think they’re both worth your time, but they do work on different levels.

fully convinced, by the Ole Miss iconography on their respective covers. I think they’re both worth your time, but they do work on different levels.