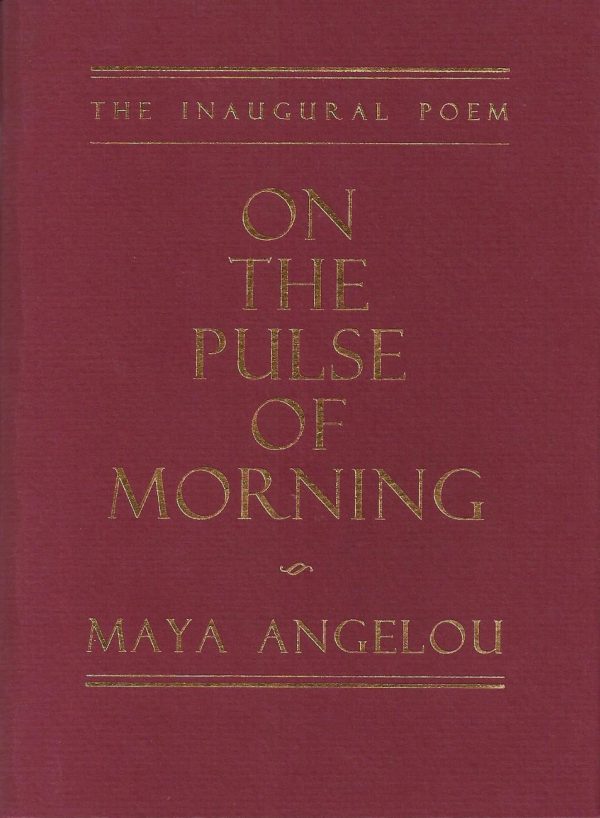

“On the Pulse of Morning” by Maya Angelou. New York, NY: Random House, 1993.

“On the Pulse of Morning” by Maya Angelou. New York, NY: Random House, 1993.

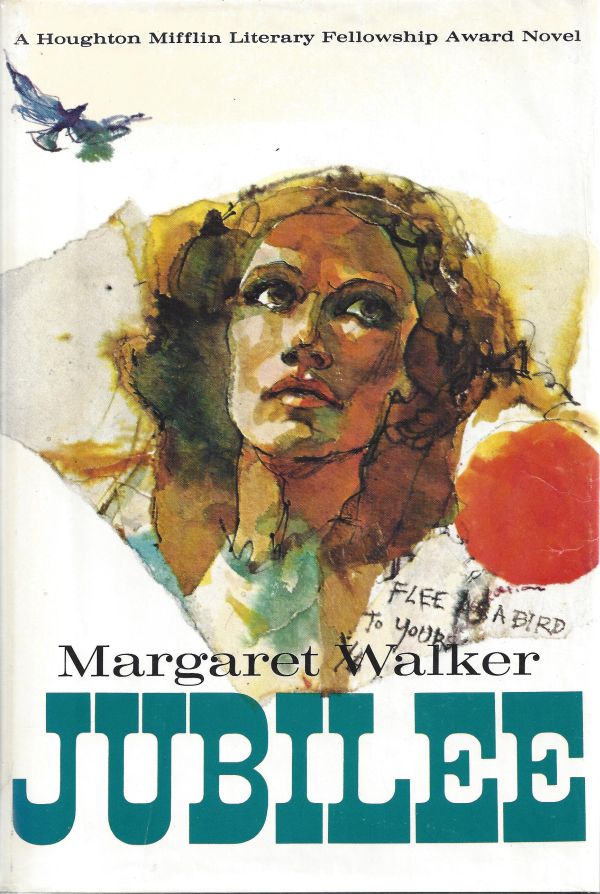

National Poetry Month was established in April 1996 to highlight the achievements of American poets, support teachers, encourage the reading and writing of poems, and increase the attention given to poetry in the media. We’ve been digging through our poetry section at Lemuria, thinking and talking about our favorite poets, and I remembered that we have a collectible edition of the late Maya Angelou’s inaugural poem “On the Pulse of Morning.”

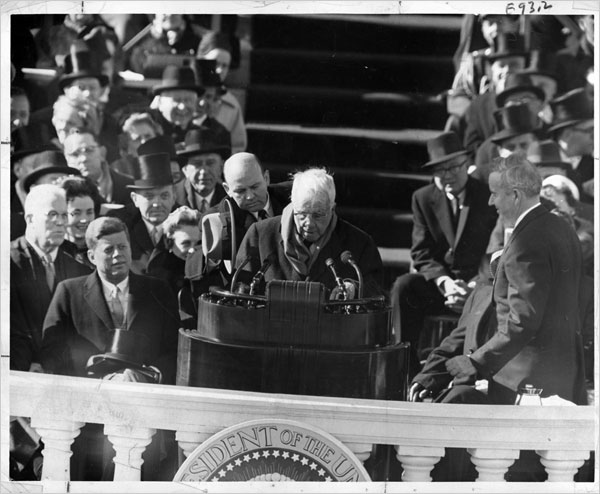

Even though the United States has had 57 presidential inaugurations, we have had only five inaugural poems. John F. Kennedy was the first to have a famous poet read at the ceremony in 1961. Robert Frost was to read a poem called “Dedication” which he had written for the occasion with references to Kennedy’s slim victory over Nixon. When Frost looked down to read, the glare was so strong from the heavy blanket of snow that he could not see the words–even though someone tried to shield the paper with his hat. The 86-year-old Frost simply recited a poem from memory called “The Gift Outright.”

It was not until 1993 that a poem was read again. Maya Angelou read “On the Pulse of Morning” at Bill Clinton’s inauguration. In a 1993 interview with the New York Times, she said that she wanted to communicate “that as human beings we are more alike that we are unalike.” As she prepared to deliver her poem, she admitted that it was an overwhelming honor. Perhaps, Angelou knew of Frost’s trouble at Kennedy’s ceremony. She asked every one to pray for her:

“I ask everybody to pray for me all the time. Pray. Pray. Pray. Just send me some good energies. Last night I said to this group of hundreds of people, I said: ‘Pray for me please, for the inaugural poem. Not in general. Pray for me by name.’ Say: ‘Lord! Help Maya Angelou’ Don’t just say ‘Lord help six-foot-tall black ladies or poets or anything like that. Lord. Help Maya Angelou. Please!’”

So far we’ve had three more inaugural poets: Miller Williams read “Of History and Hope” at the 1997 inaugural of Bill Clinton; Elizabeth Alexander read “Praise Song for the Day” at the 2009 inaugural of Barack Obama; and Richard Blanco read “One Today” at the 2013 inaugural of Barack Obama.

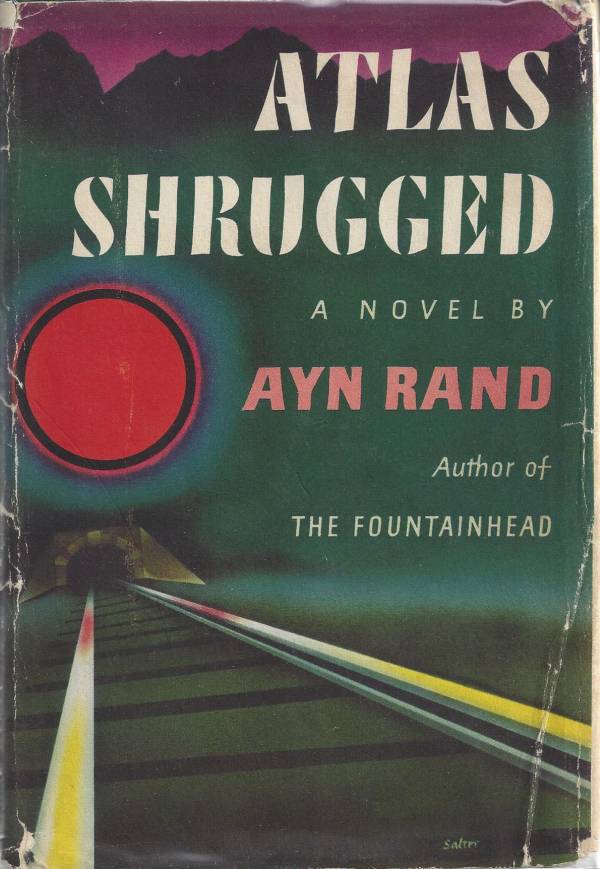

Since Robert Frost’s inaugural poem, most of the poems are published in a special inaugural edition. Random House issued Maya Angelou’s “On the Pulse of Morning” in a signed limited edition of 500 numbered copies. It was also published in a pamphlet format in dark maroon wrappers. Collecting these inaugural poets is a unique way to collect poetry and a piece of American history. It is also curious to see which presidents will carry on this tradition.

Since Robert Frost’s inaugural poem, most of the poems are published in a special inaugural edition. Random House issued Maya Angelou’s “On the Pulse of Morning” in a signed limited edition of 500 numbered copies. It was also published in a pamphlet format in dark maroon wrappers. Collecting these inaugural poets is a unique way to collect poetry and a piece of American history. It is also curious to see which presidents will carry on this tradition.

See all of Lemuria’s first editions by Maya Angelou here.

This is video footage of Maya Angelou reciting her poem “On the Pulse of Morning” at the 1993 Presidential Inaugural. This footage is official public record produced by the White House Television (WHTV) crew, provided by the Clinton Presidential Library.

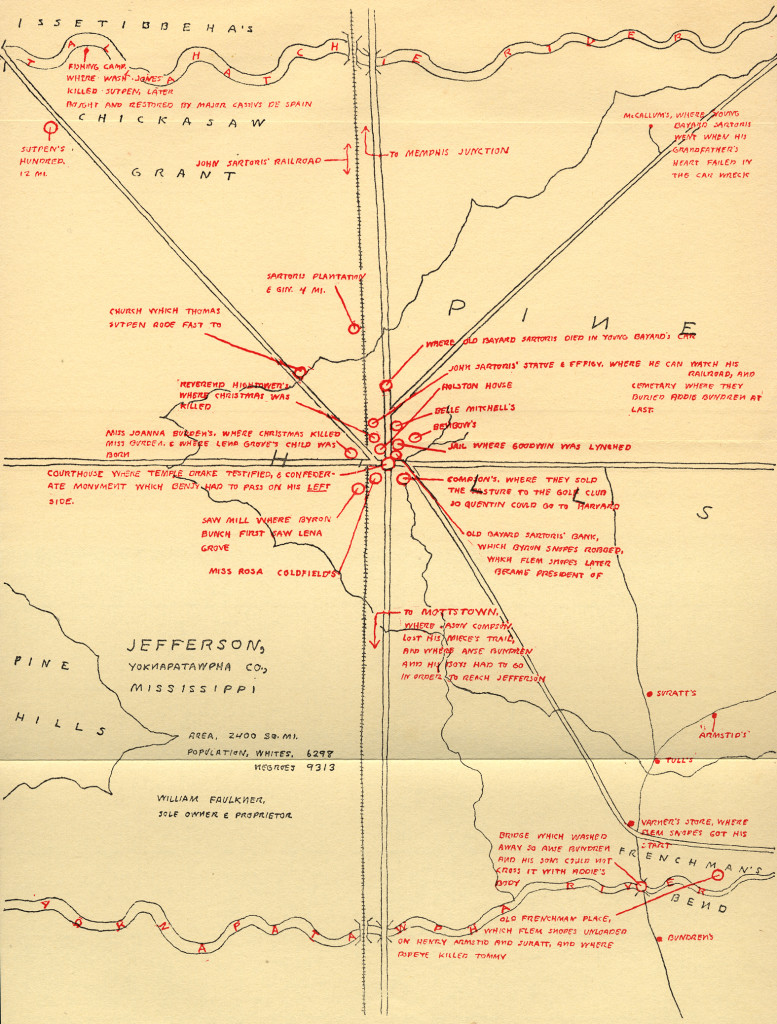

Certainly, no one was more aware of the complexity of “Absalom” than Faulkner himself. After much editorial work, Faulkner created three reader’s guides to appear at the end of the book: a genealogy, a chronology, and a map of Yoknapatawpha County. The map was special because the publisher had to pay extra to have it tipped in to the first 6,000 copies; the map was also printed in two colors. Random House was eager to make the book as beautiful as possible because “Absalom” was Random House’s first Faulkner book to publish. Earlier that year, Bennett Cerf of Random House had bought Smith & Haas, a small publisher that had been struggling to make a profit even though it had a line of great authors. Cerf wrote in his

Certainly, no one was more aware of the complexity of “Absalom” than Faulkner himself. After much editorial work, Faulkner created three reader’s guides to appear at the end of the book: a genealogy, a chronology, and a map of Yoknapatawpha County. The map was special because the publisher had to pay extra to have it tipped in to the first 6,000 copies; the map was also printed in two colors. Random House was eager to make the book as beautiful as possible because “Absalom” was Random House’s first Faulkner book to publish. Earlier that year, Bennett Cerf of Random House had bought Smith & Haas, a small publisher that had been struggling to make a profit even though it had a line of great authors. Cerf wrote in his

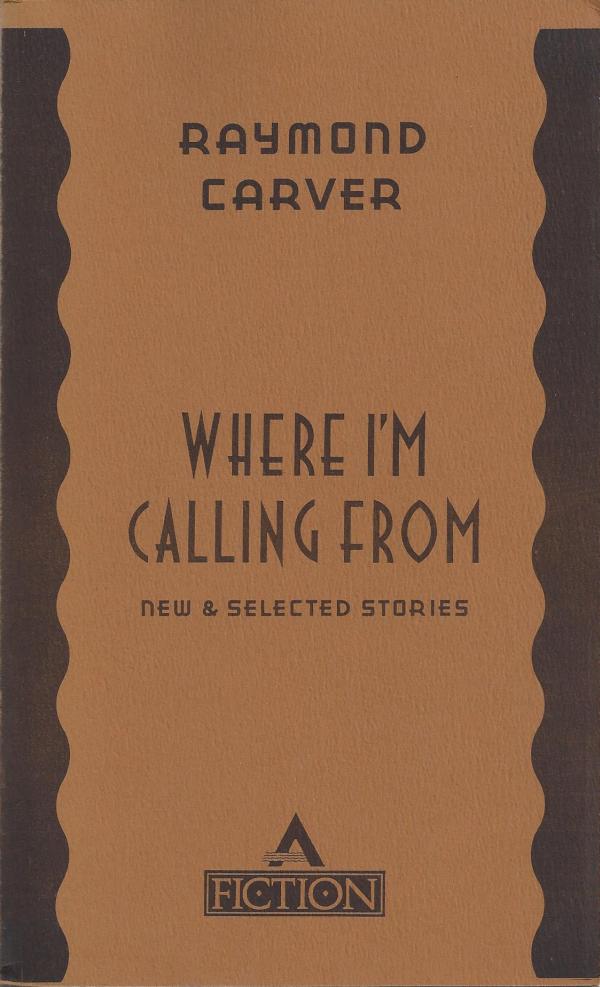

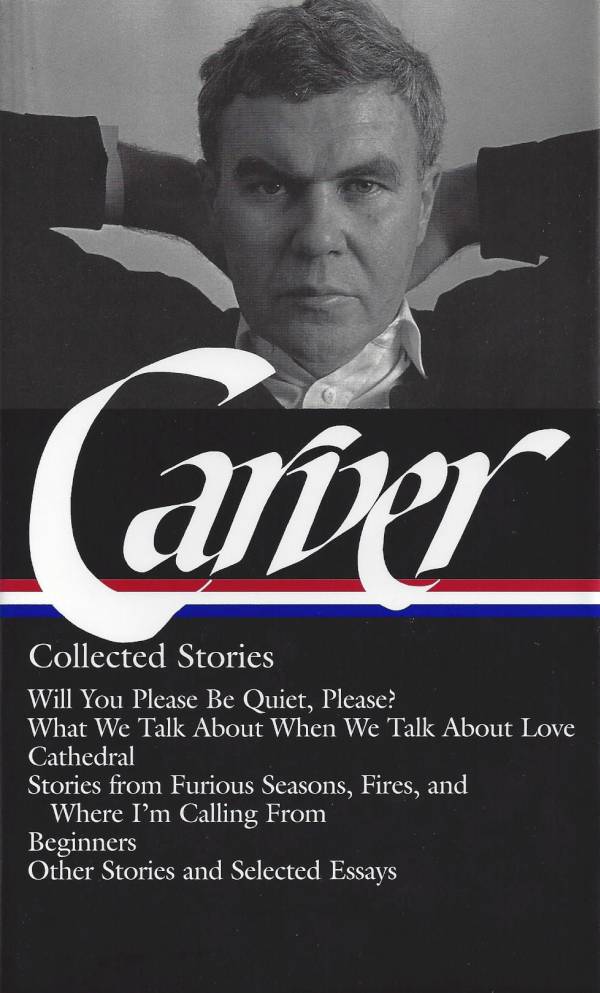

Raymond Carver died at the age of fifty but during his brief career he revived the short story form during the 1980s. His short story collection, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” made him famous and writers have sought to emulate him ever since—Tobias Wolff, Amy Hempel, Richard Ford, Ann Beattie, Alice Munro, Nadine Gordimer, William Trevor, and others. Scholars have compared their work to Somerset Maugham, Guy du Maupassant and Anton Chekhov.

Raymond Carver died at the age of fifty but during his brief career he revived the short story form during the 1980s. His short story collection, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” made him famous and writers have sought to emulate him ever since—Tobias Wolff, Amy Hempel, Richard Ford, Ann Beattie, Alice Munro, Nadine Gordimer, William Trevor, and others. Scholars have compared their work to Somerset Maugham, Guy du Maupassant and Anton Chekhov.

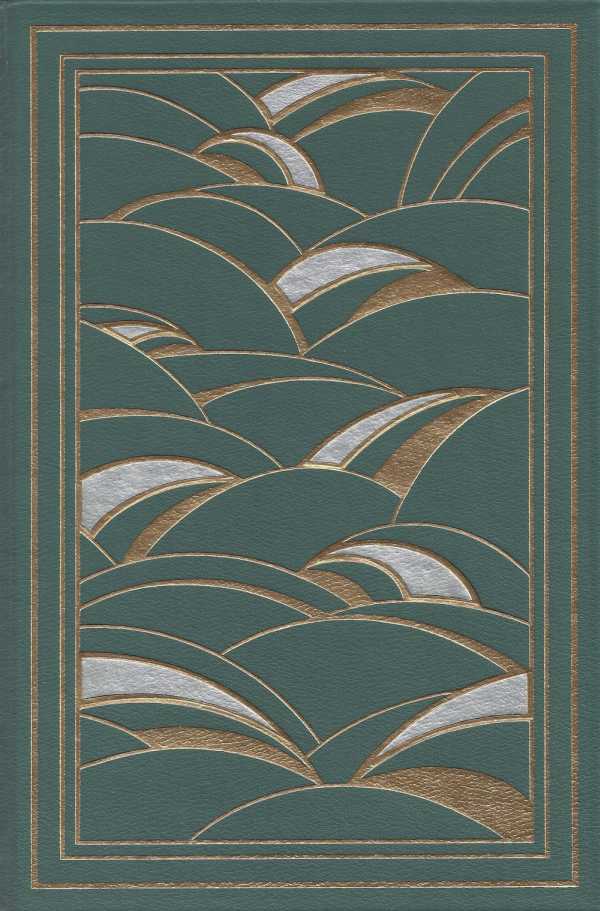

“Breathing Lessons” by Anne Tyler. Franklin Library: Philadelphia, PA: 1988.

“Breathing Lessons” by Anne Tyler. Franklin Library: Philadelphia, PA: 1988.