Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (June 24)

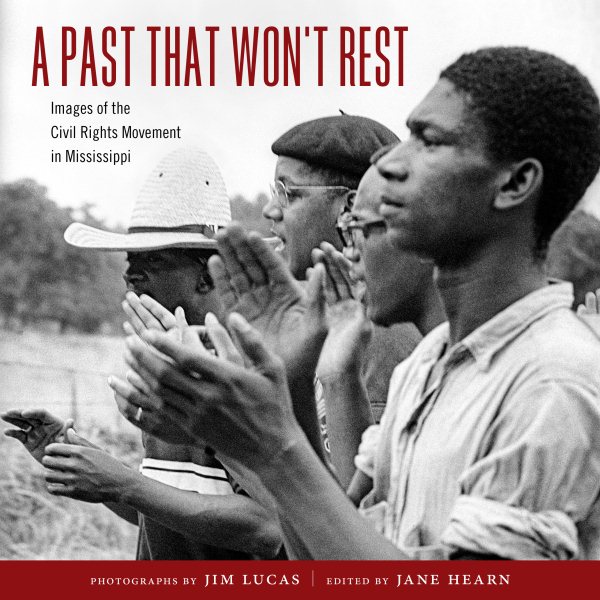

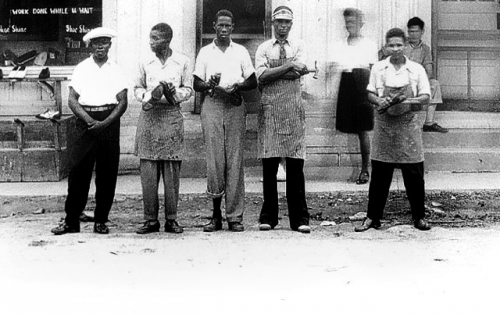

Jane Hearn shares the remarkable legacy of photographer Jim Lucas, who began shooting scenes of 1960s civil rights activism while a college student at Millsaps, in A Past That Won’t Rest: Images of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi.

The University Press of Mississippi publication features more than 100 never-before-seen photographs taken by Lucas from 1964 to 1968 that focus on four Mississippi historic events, with a fifth chapter putting recent national episodes of activist violence into historical perspective. These chapters are bolstered with narratives contributed by Dr. Howard Ball, Peter Edelman, Aram Goudsouzian, Robert E. Luckett Jr., Ellen B. Meacham, and Stanley Nelson, with a foreword by Charles L. Overby.

The University Press of Mississippi publication features more than 100 never-before-seen photographs taken by Lucas from 1964 to 1968 that focus on four Mississippi historic events, with a fifth chapter putting recent national episodes of activist violence into historical perspective. These chapters are bolstered with narratives contributed by Dr. Howard Ball, Peter Edelman, Aram Goudsouzian, Robert E. Luckett Jr., Ellen B. Meacham, and Stanley Nelson, with a foreword by Charles L. Overby.

Tragically, Lucas was killed in a car accident in 1980, while still in his mid-30s. His striking black-and-white images have been edited and restored by Hearn, who was married to Lucas at the time.

Could you share some of your background that is relevant to your relationship with photographer Jim Lucas, to put A Past That Won’t Rest into context?

Jane Hearn

I grew up in the Fondren neighborhood where my great-grandfather, grandfather, and father had a service station until 1960 on the corner of North State Street and Fondren Place. That’s back when Duling was our elementary school and all the kids in that neighborhood went to Bailey and Murrah. Our family all grew up in St. Luke’s United Methodist Church, so I am still quite attached to that area and love the resurgence that is happening there.

When my husband, Terry Stone, retired from state government about 10 years ago, we moved to the Lowcountry of South Carolina and have made that our new home. I had earlier retired from my interior design and furniture business, but continued my interest in arts advocacy and worked on projects at Tougaloo College where I served as a trustee. I was most proud of the Tougaloo Art Colony which I founded and ran for many years.

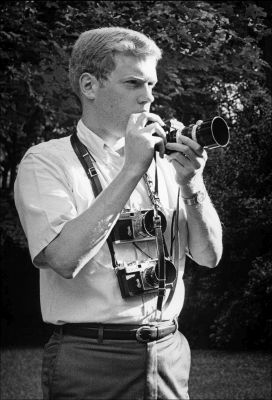

Jim Lucas and I me in 1973 when he returned to Jackson from his tour in the Army and I had just returned to Jackson after having worked a few years in New York City after college at Delta State. At the time, Jim was intent on pursuing a career as a film cameraman, which he had done during his deployment in Southeast Asia. AS a freelance film photographer, he shot advertising, football films, and news and documentary assignments for NBC and UPI. Eventually, he was able to break into his real love, feature films, and was becoming known for his exceptional technical skills as a camera operator and director of photography. He was on location for the 20th Century Fox film Barbarosa, starring Willie Nelson, when he was killed in an automobile accident.

You were married to Jim Lucas at the time of his death in 1980. Why did you decide to put this collection of his photographs, along with pertinent narratives, together to create A Past That Won’t Rest: Images of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi at this time?

This project began over five years ago with the original intent of finding a home for Jim’s extensive collection of negatives, prints, and ephemera before we moved out of state. I had kept the collection as he had stored it for over 30 years, but I felt the need to look at the images myself before I let them go. Many of the images are of high school and college life, sports, and friends, but peppered in were also newsworthy local events and images depicting historic civil rights events. Jim had always told me that there was history in his collection. I realized just how exceptional these images were and decided that it was fitting that Jim’s work should be shown to a wider audience.

I began the project with an exhibit of 35 images which previewed in June 2014 at the 50th Mississippi Freedom Summer Anniversary Conference at Tougaloo College. With support from the Mississippi Humanities Council, I was able to tour the exhibit through Mississippi for another 18 months. The book was an outgrowth of that exhibit.

Please tell me about the task that you and photojournalist Red Morgan shared in restoring these photos. Where had these photos been kept through the years, and what shape were they in? How long did this process take?

I would not have been able to do this project without Red Morgan. Red and I had only been acquaintances in high school. A mutual friend suggested I call him for help. A photojournalist and freelance photographer in Florida, Red reviewed some of Jim’s images and was excited by them. We worked together to scan, sort, edit, and produce digitalized images from over 5,000 vintage negatives. These negatives had been meticulously packaged, labeled, and documented by Jim. Our partnership in this project, along with Craig Gill and book designer Peter Halverson at the University Press of Misssissippi, has resulted in a book of 108 never-before- published photographs For all of us, this book has been a joy to produce.

Explain the process of putting this book together. How did you decide to organize it around the five narratives included? How did you choose the contributing writers? How did you narrow the selection of photographs?

As we continued to mine the collection for more photographs, we developed a website and doubled the touring exhibit. Suddenly, there were enough images for a book. The University Press of Mississippi saw the images and agreed.

The book is organized like the exhibit into four main events: the search for (civil rights workers) Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney (who were murdered in Mississippi) during Freedom Summer, 1964; the Meredith March Against Fear in 1966; the funeral of Wharlest Jackson in Natchez in 1967; and the U.S. Hearings on Poverty in Mississippi and Robert Kennedy’s subsequent trip to the Mississippi Delta in 1967.

In researching the history of these events, I was fortunate to find writers who had authored books on each. Once these scholars saw Jim’s amazing photos, they each agreed to lend their expertise with an introductory essay. Their variety of writing styles and intricate knowledge of the subject give the chapters context and lend a verbal narrative to Jim’s visual one.

The preface was written by Charles Overby, who in the mid-1960s was reporting from The Jackson Daily News while has in high school at Provine. Like Jim, Charles’ early passion and talent set him on a course for an outstanding career in journalism.

Please tell me about the touring exhibition and the website.

The early exhibit toured Mississippi in 13 venues across the state. The expanded exhibit showed last summer at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis and recently at the Brown v. Board of Education Historic Site in Topeka, Kansas.

In February, it will show at the University of South Carolina at Beaufort. The book will now be a companion catalog for the exhibit which is also called “A Past That Won’t Rest.”

An interesting thing that struck me about the book was the point that Aram Goudsouzian made about Jim capturing photos of not only the leaders, the famous people, and the drama, but also the ordinary people and events–the ones who would perform everyday tasks that would ultimately contribute to changing history, as has always been the case. Why do you think this was important to Jim?

Jim had a talent for capturing the story playing in front of his camera. He had an artistic sensibility, first to recognize the “moment,” to choose his subject, then to frame it with a discernment for good composition. His images rarely needed cropping. He shot black and white with multiple cameras (lenses), used wide angle photography and lighting with technical precision. His images reveal the emotion of the moment and the dignity and humanity of his subjects.

That day (in Yazoo County) in June 1966 on the Meredith March was hot and dusty. It was tough to walk that highway, yet through Jim’s lens we see the determination and cooperation that unified marchers of all different backgrounds who came to make sure that Meredith’s march did not fail.

Could you put the historical significance of these photos into context, especially for young people?

All of these photos and the accompanying essays depict iconic stories of Mississippians and those came to Mississippi to help in the long and arduous struggle to end violence and discrimination of black citizens.

Howard Ball’s essay on the murder of Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney tells not only this terrible tale of Klan brutality, but explains the origination of the Freedom Summer project. From 1964 through 1968, Jim’s lens allows us to see the palpable tension in the square in Philadelphia, the encouragement and pride of the marchers who rallied to assure that James Meredith’s march would meet its goal of registering people to vote, and the heartbreak and ultimate provocation of the black citizens in Natchez for the murder of a father of five whose truck was bombed for taking a job promotion that paid an additional 16 cents per hour. Peter Edelman and Ellen Meacham explain the fight over funding for the War on Poverty, a fight that continues today, and Robert Luckett draws a parallel to the grassroots organization against institutionalized violence of the 60s and that of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Jim Lucas

It’s rare that someone discovers his or her passion and future career at such a young age, but Jim was freelancing for The Jackson Daily News at age 14! Tell me about Jim–his talent, his drive, his personality.

Jim was a very humble person, almost shy, but never shy behind the camera or talking subjects photographic. The camera gave him entrance to all kinds of happenings and he had a curiosity and sensitivity for people and for animals. He was studied, measured, and loved the technical. Friends thought him the true camera nerd–in a good way! He had resolve from an early age to excel and make a mark. His work can now be included among other courageous and dedicated photojournalists of that era.

Signed copies of A Past That Won’t Rest: Images of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi are available from Lemuria.

Jane Hearn will appear at the Mississippi Book Festival Aug. 18 as a participant in the Mississippi Civil Rights panel panel at 12:00 p.m. at the C-SPAN room in Old Supreme Court Room at the State Capitol.

Subtitled “Memoir of a Civil Rights Journalist,” Dispatch is a fascinating behind-the-scenes account of the arc of his reporting, from covering the Emmett Till trial, to the Birmingham church bombing, to marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Kennedy assassination. But it’s not merely a rehashing of old events.

Subtitled “Memoir of a Civil Rights Journalist,” Dispatch is a fascinating behind-the-scenes account of the arc of his reporting, from covering the Emmett Till trial, to the Birmingham church bombing, to marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Kennedy assassination. But it’s not merely a rehashing of old events. Their new book,

Their new book,

The University Press of Mississippi, working with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, have published

The University Press of Mississippi, working with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, have published

The book, which documents the obvious racial injustice with which the case was handled by local officials, gained national attention because of the eccentric lifestyle of initial suspects Richard Dana and Octavia Dockery, who lived in a decaying antebellum home overrun with crumbling furnishings, pervasive filth–and a pen of goats, among many other animals.

The book, which documents the obvious racial injustice with which the case was handled by local officials, gained national attention because of the eccentric lifestyle of initial suspects Richard Dana and Octavia Dockery, who lived in a decaying antebellum home overrun with crumbling furnishings, pervasive filth–and a pen of goats, among many other animals.

What began for Lyon as a doctoral dissertation while he was a history student at Ole Miss more than a decade ago eventually resulted in his debut book, which unfolds in meticulous detail why activists and students at Tougaloo College acted on what they believed was a necessary element in advancing their goal of racial integration in the capital city.

What began for Lyon as a doctoral dissertation while he was a history student at Ole Miss more than a decade ago eventually resulted in his debut book, which unfolds in meticulous detail why activists and students at Tougaloo College acted on what they believed was a necessary element in advancing their goal of racial integration in the capital city.

Cultural and economic historian Gene Dattel, who grew up in the small Mississippi Delta town of Ruleville, tackles questions about what he calls “America’s most intractable problem–race”–up close and in depth in his newest book,

Cultural and economic historian Gene Dattel, who grew up in the small Mississippi Delta town of Ruleville, tackles questions about what he calls “America’s most intractable problem–race”–up close and in depth in his newest book,

But it was Nelson’s tough investigative reporting that led to his book,

But it was Nelson’s tough investigative reporting that led to his book,

Not until 1980 were Mississippi high schools allowed to use a textbook that accurately and dispassionately covered the entire history of the state, complete with the horrors of slavery, the motives behind the Civil War, the value of Reconstruction, and the triumphs of the civil rights movement.

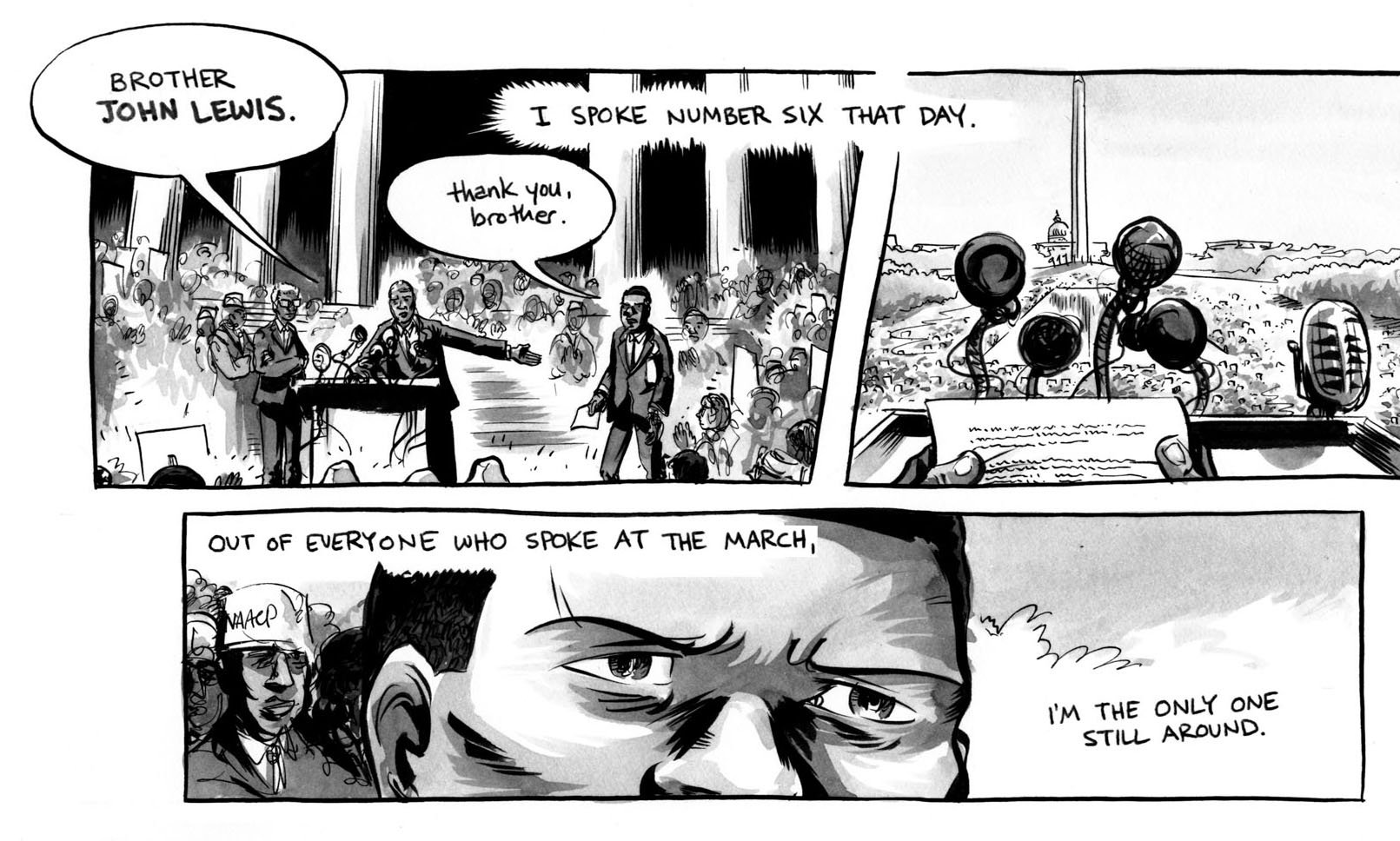

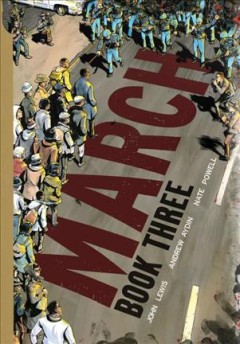

Not until 1980 were Mississippi high schools allowed to use a textbook that accurately and dispassionately covered the entire history of the state, complete with the horrors of slavery, the motives behind the Civil War, the value of Reconstruction, and the triumphs of the civil rights movement.  With the occasional jump back into the narrative present, March follows Lewis’ life using major civil rights events (the

With the occasional jump back into the narrative present, March follows Lewis’ life using major civil rights events (the  It’s also compellingly told. Lewis’ tone is conversational: it balances seriousness and grief with levity and honesty. Anyone who’s heard Senator Lewis speak knows he does so with conviction but without false airs, and March is written the same way.

It’s also compellingly told. Lewis’ tone is conversational: it balances seriousness and grief with levity and honesty. Anyone who’s heard Senator Lewis speak knows he does so with conviction but without false airs, and March is written the same way.