By Jim Ewing. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (April 22)

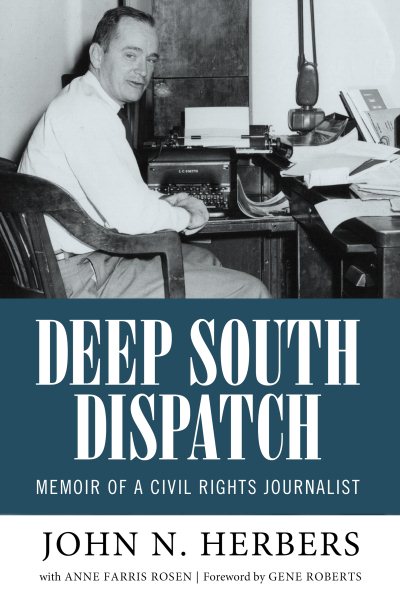

John N. Herbers might not be a familiar name today, but during the height of the civil rights movement of the 1960s, his byline blazed in The New York Times.

Herbers died last year as his book Deep South Dispatch was being edited (and ably finished by his daughter, journalist Anne Farris Rosen). But many people—especially journalists and leaders of the movement—remember him for his lucid accounts of that turbulent period when he was on the front lines and often at great danger himself.

Subtitled “Memoir of a Civil Rights Journalist,” Dispatch is a fascinating behind-the-scenes account of the arc of his reporting, from covering the Emmett Till trial, to the Birmingham church bombing, to marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Kennedy assassination. But it’s not merely a rehashing of old events.

Subtitled “Memoir of a Civil Rights Journalist,” Dispatch is a fascinating behind-the-scenes account of the arc of his reporting, from covering the Emmett Till trial, to the Birmingham church bombing, to marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Kennedy assassination. But it’s not merely a rehashing of old events.

Rather, Dispatch offers insights from a modern perspective, as well as conclusions Herbers made based on is reporting.

As Dispatch details, Herbers was not an “outside agitator,” as Mississippi politicians were wont to describe journalists back then. He was a son of the South, reared in various small towns mostly in the Memphis area, educated at Emory in Atlanta, with strong ties to Mississippi.

He began his journalism career after World War II first in Meridian, and then at the Jackson Daily News under fire-breathing publisher Fred Sullens. From there, he became bureau chief of the United Press (later United Press International) office in Jackson before going to the Times for the bulk of his writing. He was based in Atlanta, but traveled throughout the South and frequently visited his mother who lived in Crystal Springs.

Though from the South, he was at odds with the hate-filled tenor of the times. He believed his objectivity and penchant for journalism was a part of his peripatetic small-town upbringing, where “misfits” could not “escape into anonymity as they could in a city.”

Journalists, he wrote, are by nature and profession “the outlier who is always asking why.”

His love for Mississippi shines through, though, even as he was in anguish over its behavior in matters of race. Were it not for a few courageous voices against bigotry, such as Hodding Carter Sr., publisher of the Greenville Delta Democrat-Times, he wrote, “I think I would have fled Mississippi.”

Dispatch is full of names and places Mississippians remember both for good and ill. His writing is crisp and his life was Forrest Gump-like in his uncanny ability to be at signal moments. It’s encapsulated in such tales as his writing a story under a pecan tree with a manual typewriter on the top of his car at Fannie Lou Hamer’s house before going to interview powerful U.S. Sen. John O. Eastland at his plantation a few miles away.

He notes the ground-breaking reporting of Clarion Ledger reporter Jerry Mitchell that resulted in cold-case convictions of civil rights outlaws and one (of many) photographs includes him standing next to the late journalist Bill Minor of Jackson, himself worthy of note.

Dispatch is an informative, insightful, personal and telling memoir that pricks the conscience still. As he quoted Dr. King in talking about our own personal stances and how they reverberate into our culture, the greatest impediment to true justice in the world is not those oppose it, but those who are silent when they see it breached.

That’s what journalism and journalists are about, too.

Jim Ewing’s journalistic expertise as a writer and editor spans more than four decades, including The Clarion Ledger, the Jackson Daily News, and USA TODAY. A three-time winner of the J. Oliver Emmerich Award (the Mississippi Press Association’s highest honor for commentary), he has also won numerous national Best of Gannett and regional Associated Press Media Editors honors. He is the author of seven books, including his latest, Redefining Manhood.

Comments are closed.