Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (November 26)

A strategic program that was begun to awaken Jackson’s segregated white churches to the idea of opening their doors to their African-American Christian counterparts in the 1960s will be commemorated with several public events next weekend that will honor that struggle.

More than 50 years later, that effort has been documented in Carter Dalton Lyon’s Sanctuaries of Segregation: The Story of the Jackson Church Visit Campaign, published by University Press of Mississippi.

What began for Lyon as a doctoral dissertation while he was a history student at Ole Miss more than a decade ago eventually resulted in his debut book, which unfolds in meticulous detail why activists and students at Tougaloo College acted on what they believed was a necessary element in advancing their goal of racial integration in the capital city.

What began for Lyon as a doctoral dissertation while he was a history student at Ole Miss more than a decade ago eventually resulted in his debut book, which unfolds in meticulous detail why activists and students at Tougaloo College acted on what they believed was a necessary element in advancing their goal of racial integration in the capital city.

A native of Lexington, Kentucky, Lyon now teaches and chairs the History Department at St. Mary’s Epsicopal School in Memphis. He and wife Sally Cassaday are the parents of two daughters.

Your new book, Sanctuaries of Segregation: The Story of the Jackson Church Visit Campaign closely examines a 10-month effort by Tougaloo College students and activists who set out to integrate what you called “the last sanctuaries for segregationists” in the city–white churches. Why was this an important goal of the civil rights movement in Jackson in the early 60s?

One thing that I found early in my research was that segregationists throughout the South had been worrying about the potential desegregation of their churches for many years and that organized groups of students had been testing the attendance policies of white churches as they were challenging other segregated spaces. They would, in effect, conduct a sit-in at lunch counters on Saturday and try to attend white churches on Sunday. This had been done in other cities in 1960, but not in Jackson until 1963.

The idea for these “kneel-ins” was to tug at the conscience of white Christians, especially those moderates who favored a more voluntary approach to desegregation or who didn’t really appreciate the immorality of segregation. Being barred from church would make visible the reality of racial discrimination in the house of God. Activists in Jackson in 1963 had a more specific reason as well: they had tried mass marches and sit-ins, but the local movement had fractured a bit, and there were those, like Rev. Ed King, who wanted to give the Jackson community another chance to shift course–and appealing to white Christians seemed like a logical approach.

Although the participants in this movement faced a great deal of resistance from congregants and church leaders, the effort slowly began to gain some ground with white ministers and members. What was the trigger that finally broke through the resistance?

For the churches that were “open” to black visitors during the campaign, it took a combination of ministerial and lay leadership to sustain that. Even if the minister had ordered the doors to be open or favored open doors, the extent to which they would in fact be open really had to do with logistics–who was at the door and who was organizing them. The minister really needed the backing of a majority of lay leaders to make this work.

For those who began to change or who opened the doors in the years after the campaign ended, it would be nice if I could say that i was because of a change of heart, but there’s really little evidence to that effect. The Jackson church visit campaign forced their regional or national denominational bodies to clarify the open-door policies of the denomination, and so these churches needed to consent to this, especially if they wanted to call a new pastor. Some church members didn’t and formed break-away churches and, in the case of the Methodists, formed a new denomination.

Ultimately, what did this movement accomplish?

The Jackson church visit campaign made the reality of racial discrimination visible in these sacred spaces and forced white church people to confront the essential question of these activists: was racial exclusion following the will of God? These visits sparked internal debates within congregations throughout the city and certainly led to turmoil and division in many churches. But I see the church visitors as exposing a fatal flaw in these churches. They had retreated into these sanctuaries of segregation, but their practices contradicted their faith and were in defiance of the stated beliefs and policies of their own denominations. As a result of this campaign, you see denominations moving to clarify their attendance policies and become more deliberate in examining segregation within their bodies.

You write that many ministers secretly agreed with the students and activists who attempted to join in worship services in their churches, but believed they could not share their feelings with their congregations for fear of losing their jobs and/or causing a split in the church. From your research, how did these ministers ultimately deal with their mixed feelings?

Each minister dealt with it differently and there really isn’t a general way of answering this, but I can say that all of the ministers who fit this description certainly battled with the feeling that they had been called by God to this particular church and they were determined to remain. Some had been at their churches for at least a decade and even when their lay boards voted to bar African-Americans, the real moment of truth came when black visitors were in fact blocked at the church doors. For those who held onto their positions as activists were being rejected outside, I see a real sense of exasperation on the part of these ministers, that their message, and the Gospel’s message of inclusion and brotherhood over the years, had not gotten through to their congregations.

As a Kentucky native, why did you decide to bring this topic to light about Jackson’s past now, and how is it relevant in today’s social, spiritual, and/or political climate?

Carter Dalton Lyon

This book has been germinating for a while, but when I began researching this, I frankly noticed a dearth of analysis on the white church response to the civil rights movement on a local level. In the last decade and a half, historians and theologians have been doing great work filling in that gap, and I hope my book adds to that body of scholarship. The great Mississippian Ida B. Wells once wrote that “the way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth on them,” and my hope is that this book helps in some of the truth-telling that is happening in Jackson.

Your research for this book is extensive–with 65 pages of notes and bibliography. How did you go about your research, and how long did it take to put this book together?

This book grew out of my thesis and dissertation work in graduate school at the University of Mississippi, so the bulk of the research was conducted during those six years, and I’ve spent the last six years of so refining and getting it into book form. I should say that it was very important to me to try to capture all sides of this struggle and to track down as many people who were a part of this effort as I could. I realized early on that there were folks who wanted to sweep this story under the rug or deny it outright, so I aimed to be as careful and extensive as I could in documenting this and getting the story right.

Although you mention several Catholic and Protestant houses of worship, much of the book is devoted to how the “closed door” policy was carried out by Methodists. Why was that?

In the early months of the campaign, the visitors cast a pretty wide net and attempted to attend churches from a variety of denominations: Baptist, Presbyterian, Methodist, Lutheran, Disciples of Christ, Episcopal, Unitarian, Church of Christ, and Catholic. For those that routinely barred their entry, such as First Presbyterian and the Baptist churches, they reasoned that they would have little hope of cracking open those doors, so they began to focus more on the churches with regional or denominational bodies that they could use as a potential wedge against these churches.

Then about midway through the campaign, the police arrested three students outside the Capitol Street Methodist Church, and made a total of 40 arrests on subsequent Sundays, and that suddenly brought national attention on the problem of segregation within the Methodist Church ahead of the 1964 General Conference. Methodist ministers and, later, two bishops from across the country began joining students on their weekly visits for their own reasons, but certainly to expose a problem that they hoped (the conference) would solve.

Carter Dalton Lyon will appear at Lemuria to sign and read from Sanctuaries of Segregation on Thursday, November 30, at 5:00 p.m.

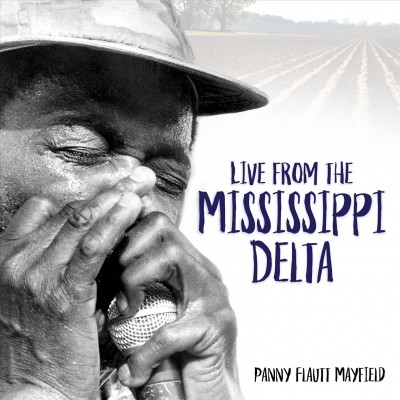

While the Coahoma County seat may not be a booming metropolis, the camera-wielding Mayfield frequently found herself in the right place at the right time, during culturally significant events and times over the past 30 years. Her casual stream-of-consciousness photo journal lets the reader in on the energy, with the perspective only a local could provide.

While the Coahoma County seat may not be a booming metropolis, the camera-wielding Mayfield frequently found herself in the right place at the right time, during culturally significant events and times over the past 30 years. Her casual stream-of-consciousness photo journal lets the reader in on the energy, with the perspective only a local could provide.

I get emotional about the cover of my book. The musician–Arthneice Jones–is one of the most talented and articulate bluesmen I have known. A harmonica master and singer/songwriter, Arthneice was leader of The Stone Gas Band–a talented and popular bunch who played all over north Mississippi and Memphis before his untimely death. A musician who worked in concrete, Arthneice intrigued, charmed, and connected intimately with Sunflower acoustic audiences each summer with sidewalk philosophy mixed with music.

I get emotional about the cover of my book. The musician–Arthneice Jones–is one of the most talented and articulate bluesmen I have known. A harmonica master and singer/songwriter, Arthneice was leader of The Stone Gas Band–a talented and popular bunch who played all over north Mississippi and Memphis before his untimely death. A musician who worked in concrete, Arthneice intrigued, charmed, and connected intimately with Sunflower acoustic audiences each summer with sidewalk philosophy mixed with music. Jim Dickinson and wife Mary Lindsay dine with Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler, famed producer Tom Dowd, Dr. John, and Mick Jagger at a Clarence Carter show. Was this a typical social occasion for Dickinson? Hardly. But his posthumous memoir,

Jim Dickinson and wife Mary Lindsay dine with Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler, famed producer Tom Dowd, Dr. John, and Mick Jagger at a Clarence Carter show. Was this a typical social occasion for Dickinson? Hardly. But his posthumous memoir,