Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion–Ledger Sunday print edition (May 13) and digital web edition

George Malvaney was a high-spirited child whose teenage years (like so many) often found him engaging in reckless behavior—fighting, drinking, and once even taking a snake to school.

While he always knew his greatest love was for the outdoors—hunting, fishing, exploring and adventure-seeking—he was certain of one thing in his life: he hated school. He dropped out during his junior year at Murrah High School and predicted he was on a “a wild and reckless stretch that would end badly.” He was right—except that it wasn’t the end.

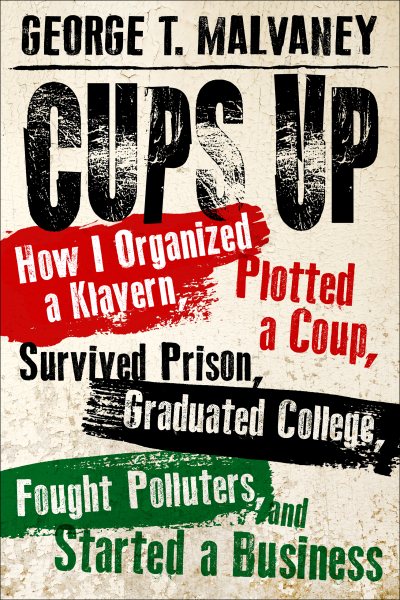

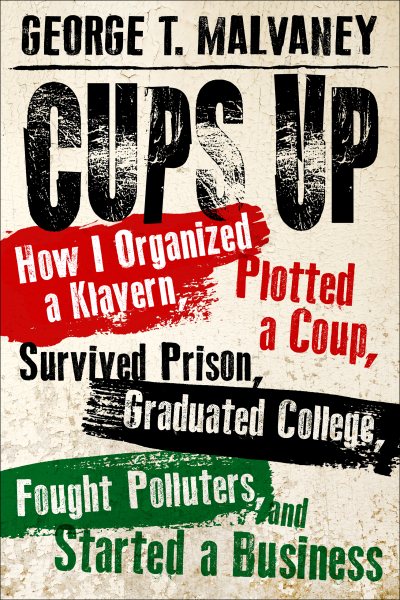

The unlikely story of this Jackson native lives up to the title of his debut book, Cups Up: How I Organized a Klavern, Plotted a Coup, Survived Prison, Graduated College, Fought Polluters and Started a Business.

The unlikely story of this Jackson native lives up to the title of his debut book, Cups Up: How I Organized a Klavern, Plotted a Coup, Survived Prison, Graduated College, Fought Polluters and Started a Business.

For a man who literally wrote the book on what not to do—and ended up not only surviving, but succeeding—he pulls off a truly hopeful tale of what it took to come out on the other side. He wrote the book, he says, to encourage and inspire others who may need a spark of hope to overcome their own challenges.

After you dropped out of Murrah High School your junior year, you joined the Navy and wound up being honorably discharged for organizing and leading a Ku Klux Klan unit on your ship. How and why were you drawn to the Klan?

That’s a good question. I get asked that a lot. I was 19 years old. At this point, 40 years later, it just doesn’t make sense to me. What would have made me do that? I don’t see why I did it. Apparently, it must have been an emotional decision. It certainly couldn’t have been logic. It was a bizarre, crazy thing. It was probably the influence of (Klan leader) Bill Wilkinson, (a friend of a friend). I did it, I own it, and I’m not proud of it.

In 1980, after your Navy experience, you fell in with Dannie Hawkins, a man you described as your “new friend and mentor,” who convinced you to join his group plotting to invade the Caribbean island of Dominica and replace the government with a right-wing, anti-Soviet regime. What was this group’s ultimate goal, and why did you decide to join their cause?

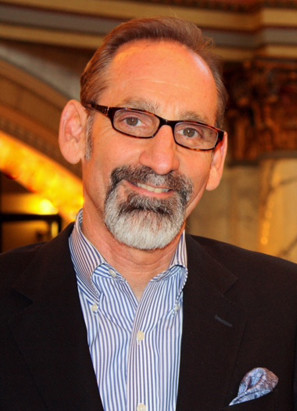

George Malvaney

There was a lot of debate as to the real reasons behind it that I was not aware of at the time. One was that they wanted to use it as a point for a cocaine smuggling ring. I never heard any of that. There must have been some ulterior motive. I was just out of the military, very patriotic, and naïve. To me it was more of an anti-Communist move to replace a government with Castro leanings to one that was more in line with American values. In hindsight, adventure and an emotional influence definitely played into it.

When the Dominican invasion plan was averted by the FBI before it ever started, you were arrested and sentenced to four years in prison, which was reduced to 18 months. Tell me about how your time in prison changed your beliefs about racial differences.

It didn’t actually change my beliefs at the time—that took years, but it started me thinking about it. When a prisoner named Leon asked me to write letters for him at the Atlanta Penitentiary, it kind of intrigued me. He was in for murder. He wanted me to write to his mother, but he didn’t want anyone to know, so he would whisper to me. He would tell me what he wanted to say, and I could feel the emotion in his voice. I couldn’t write it down the way he was saying it because he had a very limited vocabulary, but I knew what he was trying to say, so I put it in my own words.

I realized that, here’s this black guy—in for murder—and what he wanted to say was the same thing as my letters to my own family. I could see that there was good in this guy, too—lots of bad things, but, good things, too.

There were two fellow prisoners I wrote several letters for, and another I think I only wrote one letter for. The letters were very similar. Leon got a letter back from his mother and asked me to read it to him. It was clear that she was functionally illiterate herself, but I paraphrased it for him because what I knew she was trying to say.

I was in a unique situation. Here I was with black convicts opening up to me with their personal feelings. These were hard case convicts, trying to get their feelings out. It gave me a different perspective.

Tell me about how the decisions you made while in prison would change the path of your future forever.

I tell people that my time in prison was a wonderfully terrible experience that I would not ever want to repeat under any circumstances but would not trade for anything. It was one of the most valuable experiences of my life.

I was in prison because I made irrational and reckless decisions that were going to end badly. It wasn’t until my first day in federal prison in Tallahassee, Florida, that it struck me. I had a four-year sentence. I asked myself a lot of questions. How was I going to spend the next four years? Do you want to spend the rest of your life in prison? How are you going to improve? I made a very concerted decision my first day in prison: I was going to keep my head held high and get through this.

I had been making bad decisions to get to the point I was in. I didn’t how and where this would lead, but I decided my life as a convict would be done when I got out. I did not want to be involved with criminal activity, ever, when I was released.

I was in prison with murderers, bank robbers, drug dealers, kidnappers. They would become my friends, the people I was hanging out with, my peers, but I did not want to be influenced by them. It was a mental challenge. I really focused on keeping a positive mental attitude that I was going to be a better person.

When I was in the penitentiary in Atlanta, I spent months in my cell all day with almost nothing to read. I was self-examining myself. I had literally hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of hours to think about it. I looked at where I had gone wrong. I knew the Klan had been a bad decision. I knew I had to get away from those people. I decided I was going to go to college and get an education because I really wanted to become something—I didn’t know what, but it would be anything but a criminal.

After your release from prison, you went on to graduate from college and build a career based on your degree in environmental studies. Why did you choose this field?

I had thought about law school. I had seen what I thought were real injustices in prison. I wanted to try and address that, to seek some prison reform. But I came to the realization that even if I got accepted to law school, the fact that I was a convicted felon meant that I may not be able to practice law.

I had another passion, and that was the outdoors. I remembered one time, as a boy, standing on the banks of the Pearl River that went through my grandfather’s land in Hopewell, south of Jackson. An industrial plant had discharged large amounts of sulfuric acid and killed thousands of fish. I recall standing there with my father and watching dead fish float down the river for hours. It made me very sympathetic to environmental causes.

Briefly explain your role in the cleanup efforts of the BP oil spill along the Gulf coast in 2010.

I was the chief operating officer for a company that was BP’s prime contractor in Mississippi. Early on in the response effort (April 2010), I was called into some meetings with Gov. (Haley) Barbour to examine initial information pertaining to the oil spill. Mississippi didn’t have a lot of expertise in large oil spills, and I kind of became the go-to guy for Gov. Barbour and his staff. There was a big push politically to use Mississippi companies and Mississippi laborers, and I was managing 4,000 people from all over, and a $400 million budget.

The well was plugged on July 15. We saw very little oil on the mainland after that, but the barrier islands had really taken the brunt of the oil, so there was a long-term cleanup. I was able to help local mayors, supervisors and local officials, and I know I made a positive difference for Mississippi.

Tell me about your support of Big House Books, and how you found out about it.

I was at the 2016 Mississippi Book Festival and was coming out of the Authors’ Alley tent and noticed a booth that had a logo with a prisoner behind bars looking out. I saw the sign that said, “Big House Books.” They wanted to show me a loose-leaf binder filled with letters from convicts asking for book donations, but I told her I already knew what they said. I had once been locked in a hole starving for something to read. It really brought me back in time—it was an odd feeling. I dropped a $100 bill in their jar that day, and I’ve continued to support them ever since.

Please explain the title of your book.

That phrase, “cups up,” made a huge impact on me. I remember my first day in the Federal Correctional Institute in Tallahassee in July 1981. It was stifling hot. I could hear voices. They kept getting closer and closer. There was a rattling noise. I was thinking, “Why in the hell am I here? How did I get here?” They were getting closer and I was asking myself “What have I done? How am I gonna get out of here?” Then all of a sudden, a prison orderly was in front of me with a cart, and I realized I was supposed to hold my cup up for coffee. I remember having this dialogue with myself. It was a really powerful, life-changing moment.

Why did you decide to write this book, and what do you hope it will accomplish?

The Sun-Herald newspaper (in Biloxi) called me during the BP crisis. They had heard about my story and wanted to write an article about me. I did not want to do that article. I didn’t have anything to hide, but it was terrible timing. I was afraid it would all blow up in my face and distract from the BP effort.

It came out on the front page and I was just waiting for the worst—but I heard nothing but positive comments. What I heard over and over and over was “How did you go from that to leading and coordinating this massive response and dealing with the highest officials in the state?” I also heard “You need to write a book,” and I would just say that it would take a long time. But it got me thinking about it.

Part of what I wanted to do was recognize that a lot of people are having a difficult time in life, and it’s good to hear about others who have had tough times and pulled through it. I wanted to say, “Be positive, keep focused, learn what you can from it.” I wanted to give them inspiration and hope.

George Malvaney will be at Lemuria on Tuesday, May 15, at 5:00 p.m. to sign and read from Cups Up. Malvaney will also speak at the History is Lunch at the Craig H. Neilsen Auditorium at the Two Mississippi Museums on Wednesday, May 16, at 1:00 p.m.

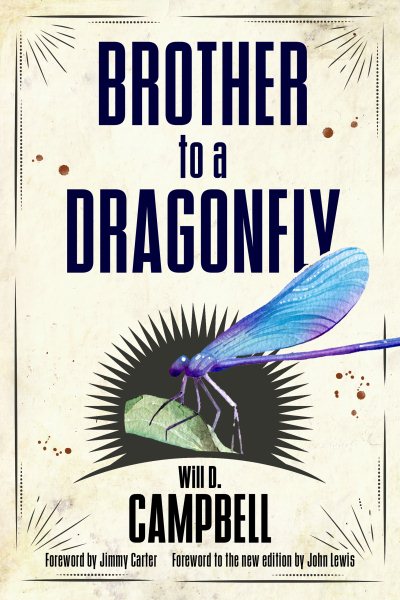

Few books could justifiably be called game-changers, but Brother to a Dragonfly was one for me when I first read it in college. It covers his formative years through the height of the civil rights movement as he became, in his words, a self-satisfied white southern liberal. You meet those, like his grandfather, the son of a Confederate soldier, who introduced him to the idea of nonviolence. From the first sentence to the last, you get to know Joe, the titular protagonist who was troubled but was ever the supportive critic, constantly pushing Will to truly evaluate his motives within the movement.

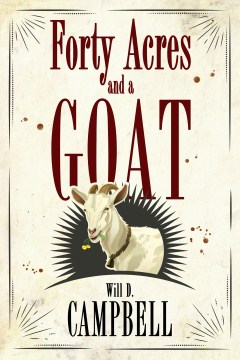

Few books could justifiably be called game-changers, but Brother to a Dragonfly was one for me when I first read it in college. It covers his formative years through the height of the civil rights movement as he became, in his words, a self-satisfied white southern liberal. You meet those, like his grandfather, the son of a Confederate soldier, who introduced him to the idea of nonviolence. From the first sentence to the last, you get to know Joe, the titular protagonist who was troubled but was ever the supportive critic, constantly pushing Will to truly evaluate his motives within the movement. Forty Acres and a Goat is a companion memoir that develops on the lessons from Brother to a Dragonfly and extends them in time as he returned to a rural home, this time to a farm outside of Nashville, Tennessee. We meet Jackson, the goat and gatekeeper to the draft-dodgers and other non-conformists who visited or found refuge in the Campbells’ company.

Forty Acres and a Goat is a companion memoir that develops on the lessons from Brother to a Dragonfly and extends them in time as he returned to a rural home, this time to a farm outside of Nashville, Tennessee. We meet Jackson, the goat and gatekeeper to the draft-dodgers and other non-conformists who visited or found refuge in the Campbells’ company.

Such is the wonder and the power of

Such is the wonder and the power of  The unlikely story of this Jackson native lives up to the title of his debut book,

The unlikely story of this Jackson native lives up to the title of his debut book,

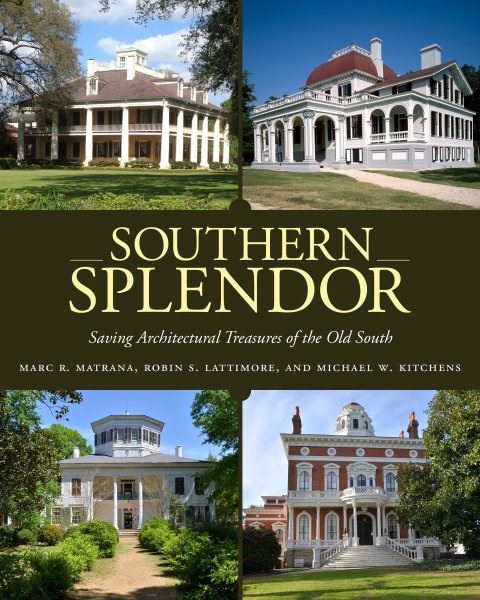

The authors document stories of these homes, with chapters devoted to Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee. The book includes 391 pages and over 275 photographs that showcase the beauty of the historic houses. Selected because of their architectural styles and restoration stories, the nearly fifty homes in Southern Splendor have overcome all types of hardships, from natural disasters and vandalism to abandonment.

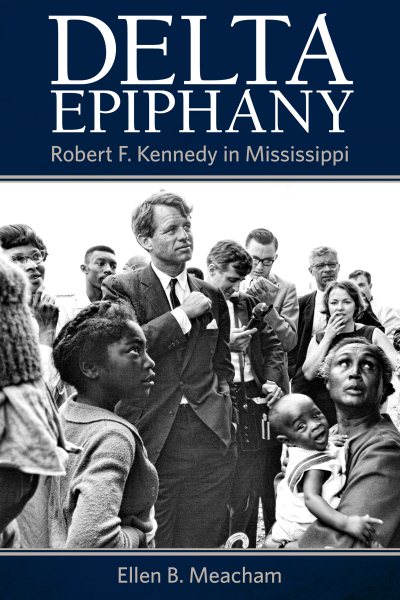

The authors document stories of these homes, with chapters devoted to Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Kentucky, and Tennessee. The book includes 391 pages and over 275 photographs that showcase the beauty of the historic houses. Selected because of their architectural styles and restoration stories, the nearly fifty homes in Southern Splendor have overcome all types of hardships, from natural disasters and vandalism to abandonment. But it goes far beyond a simple retracing of his steps here and his return to Washington that resulted in massive changes in federal food programs for the poor.

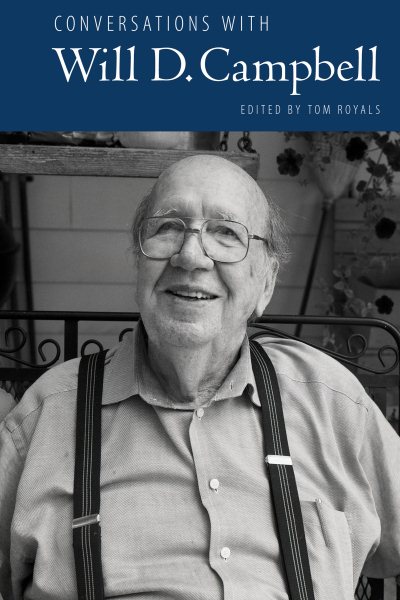

But it goes far beyond a simple retracing of his steps here and his return to Washington that resulted in massive changes in federal food programs for the poor. Campbell, an Amite County native, died in 2013, but his impact remains. He got his preaching certificate at age 17 at East Fork Baptist Church, and prized it above all his awards and degrees—including one for divinity from Yale.

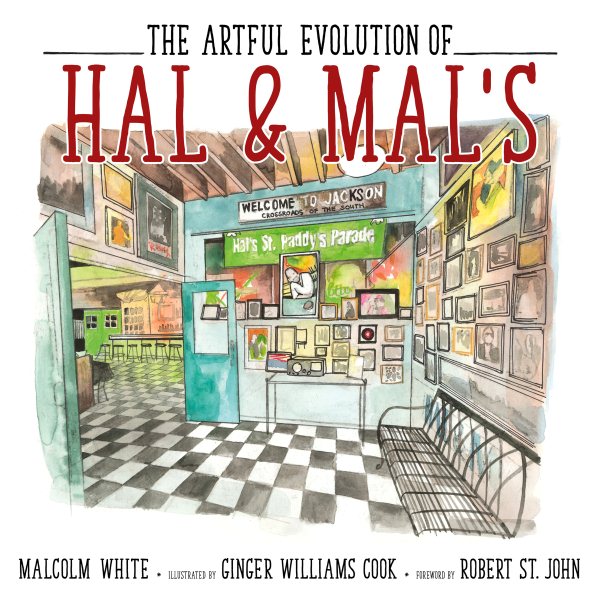

Campbell, an Amite County native, died in 2013, but his impact remains. He got his preaching certificate at age 17 at East Fork Baptist Church, and prized it above all his awards and degrees—including one for divinity from Yale. Hal & Mal’s is not one story, but many, and the book sheds a warm and witty light on the background and influences that fed into this cultural outpost in Jackson’s downtown. Of all those vines, family clings the strongest with tendrils in every story of the boys who grew up in Perkinston and Booneville, lost their mother young, and held the love of father, stepmother, brother, grandparents, relatives and friends close.

Hal & Mal’s is not one story, but many, and the book sheds a warm and witty light on the background and influences that fed into this cultural outpost in Jackson’s downtown. Of all those vines, family clings the strongest with tendrils in every story of the boys who grew up in Perkinston and Booneville, lost their mother young, and held the love of father, stepmother, brother, grandparents, relatives and friends close.

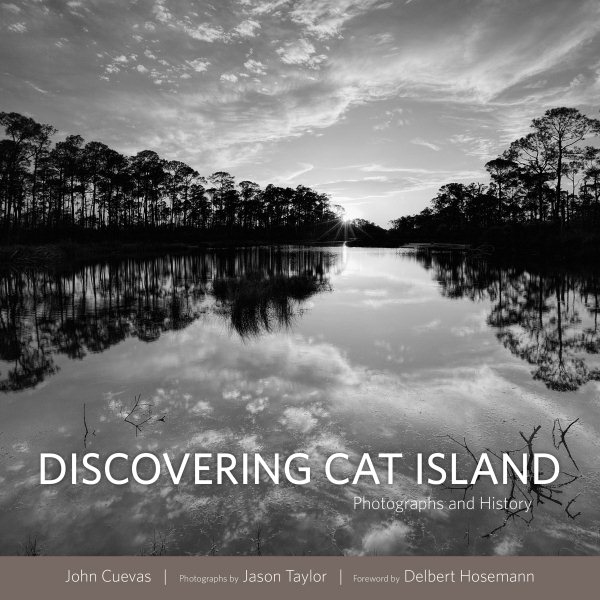

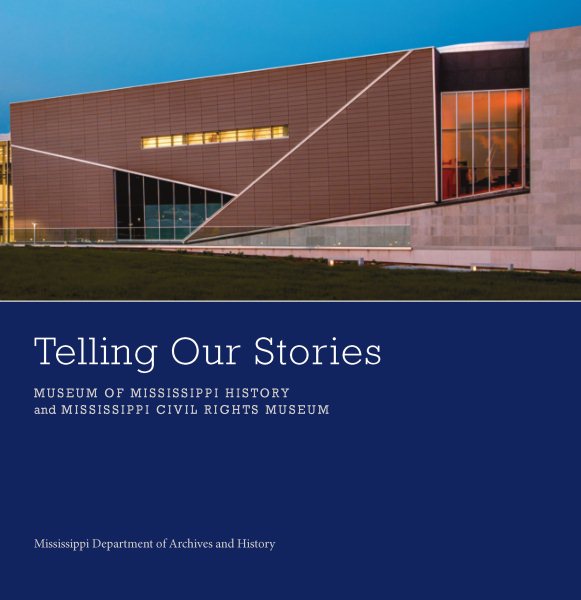

The University Press of Mississippi, working with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, have published

The University Press of Mississippi, working with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, have published

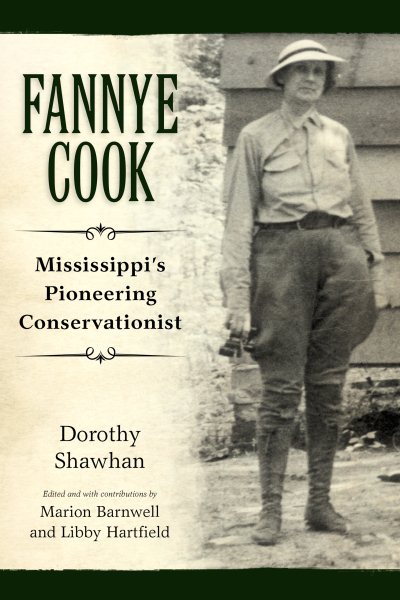

For many outdoors enthusiasts in Mississippi, Dorothy Shawhan’s book

For many outdoors enthusiasts in Mississippi, Dorothy Shawhan’s book