Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (July 23)

As the editor of his hometown’s weekly newspaper–the Concordia Sentinel in Ferriday, La.–Stanley Nelson didn’t set out to become a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize in Local Reporting. He didn’t plan on his investigative journalism becoming the basis of a blockbuster fictional trilogy by New York Times bestselling author Greg Iles. And he never dreamed his efforts would build a crusade for justice that would draw dozens of willing supporters from around the country.

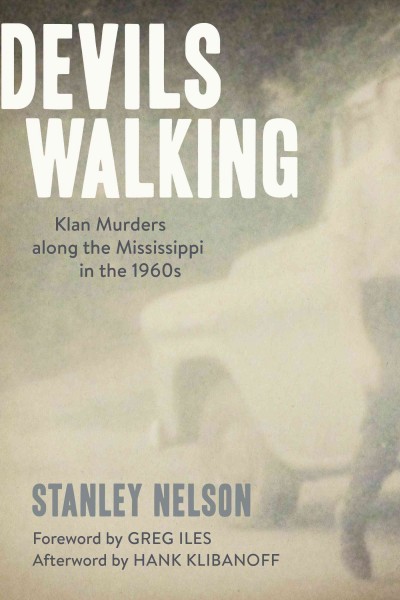

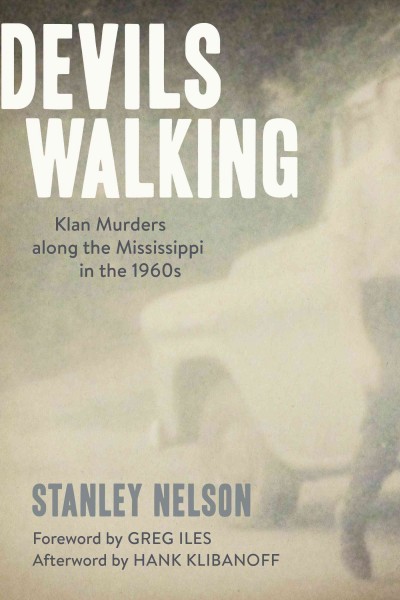

But it was Nelson’s tough investigative reporting that led to his book, Devils Walking: Klan Murders along the Mississippi in the 1960s (LSU Press), in which he describes not only the difficulties of pursuing decades-old cold cases of racial injustice, but the remarkable successes that he and his collaborators were able to achieve–even when the FBI could not.

But it was Nelson’s tough investigative reporting that led to his book, Devils Walking: Klan Murders along the Mississippi in the 1960s (LSU Press), in which he describes not only the difficulties of pursuing decades-old cold cases of racial injustice, but the remarkable successes that he and his collaborators were able to achieve–even when the FBI could not.

As a testament to Nelson’s tenacity and courage to take on this topic, Iles dedicated Natchez Burning, the first installment of his fictional trilogy, to the Ferriday reporter who, with the help of a large team, stopped at nothing to find answers to so many questions that had lingered for 50 years. Inspired by Nelson’s work, Iles used pieces of the massive puzzle that was unraveled as a basis for some plot material for his trilogy that included The Bone Tree and Mississippi Blood. In fact, it was Iles who wrote the forward to Nelson’s book, offering high praise for the journalist’s accomplishments.

At the heart of Nelson’s book is the story of one man–Frank Morris of Ferriday–whose tragic fiery death at the hands of the notorious Klan cell known as the Silver Dollar Group in 1964 would eventually lead to further investigations, and, in one case, even a grand jury hearing.

From his first awareness of the Morris case in 2007, prompted by the FBI’s initiative to reopen Civil Rights-era cold cases, Nelson would write nearly 200 news stories about the murder, over a seven-year time period. In addition to the Sentinel in Ferriday, his award-winning investigative writing would appear in the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and on CNN and National Public Radio.

A discussion about the events in both Iles’ and Nelson’s books will be led by Clarion-Ledger investigative reporter Jerry Mitchell at the Mississippi Book Festival on Aug. 19. The event will begin at 1:30 p.m. in the Galloway United Methodist Church sanctuary in Jackson.

Devils Walking, a detailed examination of Klan murders committed by the Silver Dollar Group in Mississippi and Louisiana during the 1960s, revolves around the story of the brutal killing of Frank Morris in Ferriday, La. in December 1964. As a reporter for Ferriday’s newspaper, the Concordia Sentinel, what sparked your interest in this case in 2007?

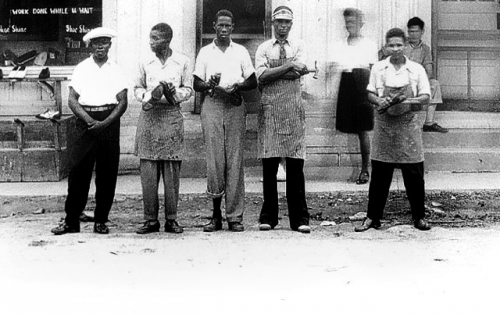

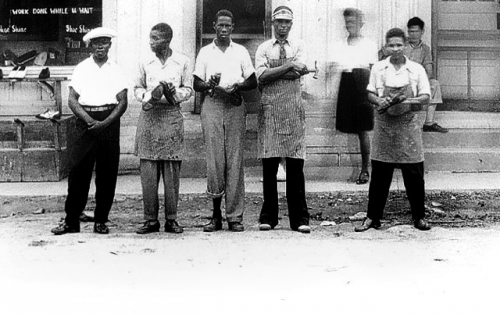

Frank Morris in front of his shoe shop (wearing visor, near center)

In late February 2007, the FBI and Justice Department announced they were taking a second look at approximately 100 unsolved civil rights-era murders. Frank Morris’ name was on the list. Morris died from burns he received when Klansmen torched his Ferriday shoe shop and deliberately incinerated him as well.

I initially wrote a couple of stories. Then I got a phone call from Frank Morris’ granddaughter, Rosa Williams. She thanked me for the coverage and said that she had learned more about her grandfather’s death in the first article than she had in the previous decades. Of all of the questions she had about the murder, the biggest was “Why?”

When I was young, I witnessed the aftermath of a horrible traffic accident in which a young family, including a 7-year-old girl, died in flames. Considering that and the murder of Frank Morris, I wondered how someone could purposely set a human being on fire? It was a question that would not go away. I talked to the Sentinel‘s publishers. They agreed that we should try to find out what happened.

Explain how and why this case grew into such a large investigation–with the help of, among others, 25 students at the Syracuse University School of Law–in such a short time.

Race is a polarizing topic. So, could I get readers to open their minds and hearts to the Morris story? I figured that if they got to know Frank Morris, they would care about him. Then justice would seem important. So, week after week we tried to bring Frank Morris back to life so that our readers would see him as a living, breathing human being–not a ghost from the past.

A lot of people lent me a hand–some included Syracuse University College of Law professors Janis McDonald and Paula Johnson; the Center for Investigative Reporting; the LSU Manship School of Mass Communication; Teach for America; and summer interns from universities in the South. Canadian filmmaker David Ridgen was a constant help. But nothing would have happened without the Sentinel’s publishers–Lesley Hanna Capdepon and Sam Hanna Jr.–who supported the work through thick and thin.

By 2007, as the FBI, the Department of Justice and a contingent of government investigators were becoming involved with this case, there was urgency to move the investigation forward. Why was this?

In the 1960s, dangerous Klansmen at the height of their power menaced anyone who questioned the terror they engendered. But by the 2000s, those men were dead or dying. The new enemy to justice became “time.” Witnesses were dying, too. So, urgency was mandated.

Explain the assistance that Jerry Mitchell, investigative reporter for the Clarion-Ledger, was able to lend to your own investigation of Klan murders in Mississippi.

Jerry is considered a legend in the world of cold case investigations. I often seek his advice and he always helps.

When did Louisiana State University get on board to join the investigation, and what contributions did they make?

Jay Shelledy of the LSU Manship School invited me to talk to his journalism students. Later, then dean of the Manship School Jack Hamilton asked, “How can we help you?” I answered that I needed FBI Klan files from the National Archives.

Since then, Jay and his students have amassed tens of thousands of pages of FBI documents, approaching 200,000 pages, all now on line on their website (http://lsucoldcaseproject.com/). Their amazing work continues with new students every year and the full support of Dean Jerry Ceppos. Former Interim Dean Ralph Izard was fully behind the project as well.

In the end, you have a theory of who was actually responsible for Frank Morris’s murder–but has it been proven, or can it be proven?

A Concordia Parish deputy, Frank DeLaughter, wanted Morris’ shop burned following a verbal confrontation with him. DeLaughter considered Morris an uppity black man and he wasn’t going to stand for that.

FBI agents in the field were convinced DeLaughter was the mastermind of the arson. A retired agent recently deceased–John Pfeifer–spent 10 years in Concordia Parish back then. Pfeifer said the one thing FBI agents couldn’t do in the 1960s was directly link DeLaughter to the arson. Fortunately, we were able to do that in 2010.

Relatives of admitted Klansman Arthur Leonard Spencer of Rayville, La., including his son, said Spencer had discussed his involvement in the Ferriday arson through the years. They also said a family friend–Coonie Poissot–told them he was involved as well.

Described by the FBI as a drifter, Klansman, thug, and speed addict, Poissot revealed to agents in 1967 that he was with DeLaughter the night before the arson and that as they passed the shoe shop in DeLaughter’s patrol car, the deputy said he planned to teach Morris a lesson. The following night, Morris watched his two attackers as they torched the building. He didn’t know them.

DeLaughter and Poissot died in the 1990s. Following our story on Spencer in January 2011, three separate Concordia Parish grand juries heard from witnesses in the case, but took no action and issued no reports. After Spencer died in 2013, the Justice Department said it didn’t believe Spencer had been involved. Yet the U.S. Attorney’s office in Louisiana considered him a prime suspect.

You have also investigated the cold case deaths of other African Americans at the hands of the Silver Dollar Group, described as the most secretive and dangerous in the nation at the time. What has driven you to pursue these injustices in such depth? How many stories did you ultimately write?

I’ve written approximately 200 stories. Like Frank Morris, all of these cases are compelling. The victims are ordinary folks who have suffered extraordinary pain.

Additionally, discovering the inner workings of the Silver Dollar Group was a fascinating journey. These men, including Frank DeLaughter, were incredibly successful terrorists for two reasons. One, in small numbers, typically three or four men, they committed these crimes. Two, they kept their mouths shut.

The group’s leader–Red Glover–who may have acted alone in the 1967 bombing of NAACP Treasurer Wharlest Jackson in Natchez, was interviewed several times by FBI agents after Jackson’s murder. On one occasion, Glover told the agents he hoped they caught the murderer because, according to Glover, the killer obviously was “a maniac.”

Natchez author Greg Iles’ blockbuster trilogy of Natchez Burning, The Bone Tree, and Mississippi Blood was based on you and your work to solve these cold cases. Please comment on the significance of that honor.

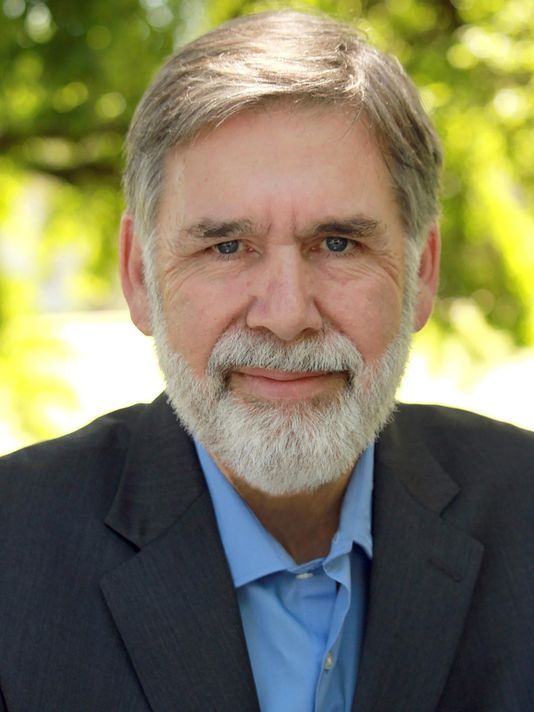

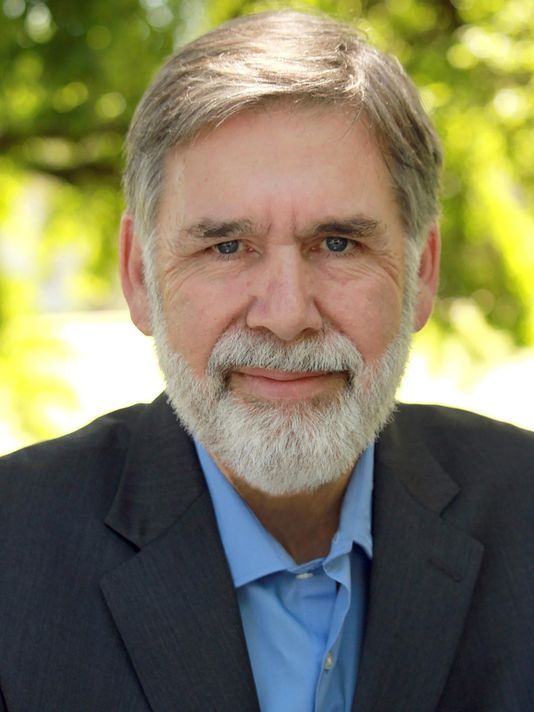

Stanley Nelson

In 2013 (Greg) handed me a galley of Natchez Burning. He signed the title page: “To Stanley Nelson: The Real Henry Sexton.” I’ll never forget it. Greg was born with a gift for writing, and he continues to become better at it. But, in my opinion, his genius is his research.

You were named a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize in Local Reporting in 2011, as a result of your investigation of these cases. How has that impacted you personally and professionally?

It was totally unexpected. I never thought the Sentinel would emerge at the top of the list against stories such as WikiLeaks and the BP Oil Spill. It also means that the stories of Frank Morris and the other victims may live on.

Is there anything else you’d like to include?

The book covers the emergence of the Silver Dollar Group (SDG) from the three traditional Klans. The SDG’s goal was simple–go underground and fight integration with deadly force. Red Glover hand-picked the members and as a symbol of unity gave many a silver dollar minted in the year of the Klansman’s birth. Southwest Mississippi and Concordia Parish, Louisiana, (across the river from Natchez) had seen at least four SDG murders by July 1964, three occurring before the Neshoba murders and the fourth occurring just days afterward. Eight SDG murders are covered in the book as well as the killing of Johnny Queen in 1965 in Fayette.

Additionally, the book questions the FBI and Justice Department’s new probes into the murders. Since the initiative was announced in February 2007, only one re-opened case moved forward–the grand jury probe into the Frank Morris arson. For the most part, the government’s initiative was a failure and we discuss why.

All the familiar denizens of the fictional town of Jericho, Mississippi, (faintly like the Oxford we all know, perhaps stripped to its roots) are there–if not in person, then in memory.

All the familiar denizens of the fictional town of Jericho, Mississippi, (faintly like the Oxford we all know, perhaps stripped to its roots) are there–if not in person, then in memory.

But it was Nelson’s tough investigative reporting that led to his book,

But it was Nelson’s tough investigative reporting that led to his book,

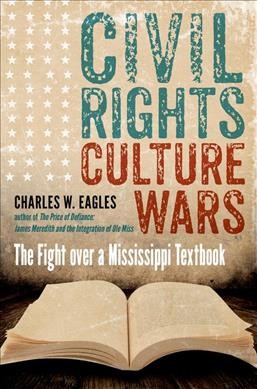

Not until 1980 were Mississippi high schools allowed to use a textbook that accurately and dispassionately covered the entire history of the state, complete with the horrors of slavery, the motives behind the Civil War, the value of Reconstruction, and the triumphs of the civil rights movement.

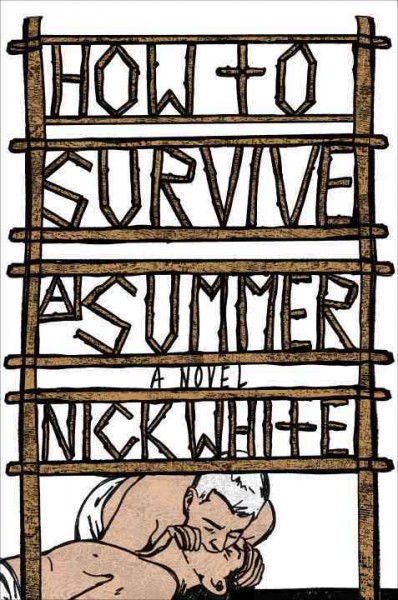

Not until 1980 were Mississippi high schools allowed to use a textbook that accurately and dispassionately covered the entire history of the state, complete with the horrors of slavery, the motives behind the Civil War, the value of Reconstruction, and the triumphs of the civil rights movement.  White’s debut novel is about a man who, as a teenager, went to a gay-to-straight conversion camp in Mississippi. When the story of the camp is made into a movie, the main character, Will Dillard, returns to his roots and finally reckons with his past. The story is told through memories and reads almost like a memoir, as it focuses on emotions and is told primarily through internal dialogue. But the plot–the truth of what really happened that summer–kept me turning pages.

White’s debut novel is about a man who, as a teenager, went to a gay-to-straight conversion camp in Mississippi. When the story of the camp is made into a movie, the main character, Will Dillard, returns to his roots and finally reckons with his past. The story is told through memories and reads almost like a memoir, as it focuses on emotions and is told primarily through internal dialogue. But the plot–the truth of what really happened that summer–kept me turning pages. Greg Iles is set to publish his final chapter in the Natchez Burning trilogy tomorrow. The trilogy, which began with

Greg Iles is set to publish his final chapter in the Natchez Burning trilogy tomorrow. The trilogy, which began with  It the middle of Turning Angel, he makes a pitch for his out-of-town fiancée to stay while he makes a run for mayor of Natchez: “Natchez has become a place where we have to raise our children to live elsewhere. Our kids can’t come back here and make a living. And that’s a tragedy…I want to change that.” And those words resonate because what’s true for Natchez is essentially true for all of Mississippi.

It the middle of Turning Angel, he makes a pitch for his out-of-town fiancée to stay while he makes a run for mayor of Natchez: “Natchez has become a place where we have to raise our children to live elsewhere. Our kids can’t come back here and make a living. And that’s a tragedy…I want to change that.” And those words resonate because what’s true for Natchez is essentially true for all of Mississippi. Truly menacing villains such as Brody Royal, the money man behind the Klan, and Forrest Knox, the heir apparent to all law enforcement in Louisiana and simultaneously the head of the family crime syndicate, dominate the first two books, but are dispatched. By the telling of Mississippi Blood, only Snake Knox (Forrest’s uncle), the man with the meanest of goals—survival and notoriety—and the meanest of dispositions, survives to torment Penn and the good people left standing in Natchez.

Truly menacing villains such as Brody Royal, the money man behind the Klan, and Forrest Knox, the heir apparent to all law enforcement in Louisiana and simultaneously the head of the family crime syndicate, dominate the first two books, but are dispatched. By the telling of Mississippi Blood, only Snake Knox (Forrest’s uncle), the man with the meanest of goals—survival and notoriety—and the meanest of dispositions, survives to torment Penn and the good people left standing in Natchez.