Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger (January 27). Click here to read this interview on the Clarion-Ledger’s website

For those of us who continue to promise ourselves we’re finally going to make a clean sweep and part with material objects we’ve long held onto for their sentimental value–but from which we really draw little joy–Chris Cander starts 2019 with The Weight of a Piano (Knopf), a gentle push to examine when it’s time to let go.

For those of us who continue to promise ourselves we’re finally going to make a clean sweep and part with material objects we’ve long held onto for their sentimental value–but from which we really draw little joy–Chris Cander starts 2019 with The Weight of a Piano (Knopf), a gentle push to examine when it’s time to let go.

In this fictional tale, two women–years and miles apart–unknowingly share such an attachment to the same antique German-made Blüthner piano. The novel “plays out” the story of how the women came to love the same lovingly handcrafted piano while in the midst of very different relationships and life circumstances–and why examining what your heart is really telling you is what matters most.

The author of the previous novels Whisper Hollow and 11 Stories, Cander has also dedicated her talents to encourage children to discover the power of reading and writing, through her work as a writer-in-residence for the Houston-based Writers in the Schools program, and her support of Little Free Libraries in her area. She also writes children’s books and screenplays.

A member of the American Society of Journalists and Authors, Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, the Author’s Guild, the Writers’ League of Texas, PEN, and MENSA, Candor lives with her husband and children in Houston, Texas.

The plot of The Weight of a Piano is filled with nuances that point to the eventual and unexpected fate of a piano, which has a long and interesting history. Did the idea for this story come from your own musical interests or talents?

Actually, the idea of centering the story on a piano didn’t come from a musical perspective at all. Not long after I lost both my grandmothers, I overheard a woman talking about finally letting go of a piano her father had given her when she was a child. She’d been taking lessons for a few months when he suddenly died, and afterward, it became a symbol of her grief–and of him. She didn’t play it, but also couldn’t get rid of it. It struck me how heavy certain possessions with provenance can be, and I knew then that I wanted to unpack that idea in a novel.

The title of the book is a clever take on the actual heaviness of a piano as measured in pounds, contrasted with the emotional weight, which the characters find themselves bearing. How did you come up with this theme?

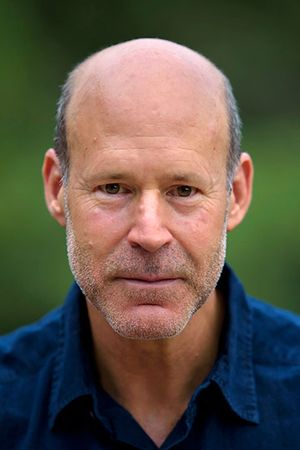

Chris Cander

I can remember when I was in college, and everything I owned fit into my car. Now I look around my house and wonder, how did I end up with all this stuff? In addition to the typical possessions of an American family of four, I’ve inherited treasures from a large number of artists and collectors: the cedar chest my grandfather made, the chair that had belonged to my mother-in-law, artwork painted by friends, trinkets given to me by my children, and much, much more.

It can be both a blessing and a burden to own so much. It’s one thing to keep an out-of-style heirloom quilt or a broken watch that belonged to a grandparent, but it was fascinating to me to imagine what it would be like to carry an unwanted, 560-pound object through life. How does that kind of albatross affect someone? And what will she do to get out from underneath it?

There are many hints in the book of the meaning of the piano to its former and present owners. What does this story say for all of us about the meaning we place on objects?

You’ve heard the adage: “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.” I’m fascinated by the different relationships we can have to things. From the minimalist movement to hoarding and everything in between, we–and here I’m speaking of a certain swath of contemporary American culture–seem particularly concerned with what and how much we own. Does it spark joy? has become an easy qualifier for what we decide to keep.

But some objects come into our lives freighted by so much more than joy. The stories that come with them–including the ones we tell ourselves–can trick us into thinking something ordinary is extraordinary, imbued with a sentimental value far greater than its actual worth. We all react to these physical things differently.

Tell me about your writing process. Do you create much of the plot first, and then develop the characters, or is it always different?

Typically, ideas are carried into my imagination on the shoulders of their protagonists, though as I mentioned, this novel was inspired by an event–that of a girl being given a piano by her father, who then dies shortly thereafter. But even the most compelling events don’t carry a story forward; it’s how the people who endure these events react to them, revealing their unique qualities and, hopefully, something about human nature in general.

Do you have another book in the works yet?

Happily, yes. I’m about halfway through a novel titled Zephyr, which explores the unseen forces that affect and connect us all.

Chris Cander will be at Lemuria on Wednesday, January 30, at 5:00 p.m. to sign copies of The Weight of a Piano. She will be in conversation with Knopf editor Gary Fisketjon at 5:30 p.m. The Weight of a Piano is Lemuria’s January 2019 selection for its First Editions Club for Fiction.

The Weight of a Piano surprised me in the amount of technical detail Cander used when describing musical technique and the titular piano. It is so easy to see Katya’s love of music throughout the novel, which is portrayed by Cander’s poetic description of the piano and the music played on it. I was easily able to relate to Katya and the way music brings her joy and conveys her feelings, as well as the way music connects characters to one another, even across time, because I often feel this way about classical music. As a classical musician, it also felt extra special to be able to understand Katya’s emotional connection to the piano and the music she plays on it.

The Weight of a Piano surprised me in the amount of technical detail Cander used when describing musical technique and the titular piano. It is so easy to see Katya’s love of music throughout the novel, which is portrayed by Cander’s poetic description of the piano and the music played on it. I was easily able to relate to Katya and the way music brings her joy and conveys her feelings, as well as the way music connects characters to one another, even across time, because I often feel this way about classical music. As a classical musician, it also felt extra special to be able to understand Katya’s emotional connection to the piano and the music she plays on it. The award-winning novelist’s portrayal of a good-natured man whose hopes and dreams are literally forgotten when his memory is wiped out after “his Pontiac flies off a bridge into the icy depths of Lake Superior” is at once contemplative and relatable.

The award-winning novelist’s portrayal of a good-natured man whose hopes and dreams are literally forgotten when his memory is wiped out after “his Pontiac flies off a bridge into the icy depths of Lake Superior” is at once contemplative and relatable.

On the 20th anniversary of The Poisonwood Bible, Barbara Kingsolver gives us a timely novel in

On the 20th anniversary of The Poisonwood Bible, Barbara Kingsolver gives us a timely novel in  In

In  But in

But in  Stephen Markley’s gripping debut novel

Stephen Markley’s gripping debut novel  National Book Award finalist Elliot Ackerman shows his grit as both a tested warrior and intrepid wordsmith with his new release

National Book Award finalist Elliot Ackerman shows his grit as both a tested warrior and intrepid wordsmith with his new release

His circuitous educational route set him on the path to the notable success of Bearskin, a rough and tumble thriller that contrasts the brutality of human capability with the primitive beauty of nature’s untouched wilds. Set in a remote private nature reserve in the heart of Appalachia, the story plays out with a precarious mix that includes a hostile drug ring, a love interest, a regretful past, hallucinatory episodes–and mutilated bears whose body parts have been stolen for drug-dealing profiteers. In brief, it runs the gamut from wild action to deep contemplation and plenty of raw secrets.

His circuitous educational route set him on the path to the notable success of Bearskin, a rough and tumble thriller that contrasts the brutality of human capability with the primitive beauty of nature’s untouched wilds. Set in a remote private nature reserve in the heart of Appalachia, the story plays out with a precarious mix that includes a hostile drug ring, a love interest, a regretful past, hallucinatory episodes–and mutilated bears whose body parts have been stolen for drug-dealing profiteers. In brief, it runs the gamut from wild action to deep contemplation and plenty of raw secrets.