By J. Richard Gruber. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (September 22)

O.W. “Pappy” Kitchens was a distinctive Mississippi character. He was a building contractor and house mover, as well as an accomplished storyteller, who, after he sold his business and retired, discovered that he was an artist.

O.W. “Pappy” Kitchens was a distinctive Mississippi character. He was a building contractor and house mover, as well as an accomplished storyteller, who, after he sold his business and retired, discovered that he was an artist.

“I began to draw and sketch and found my experience in drafting was a big help in this adventure.” He was, he explained, a specific type of artist. “I am a folk artist. I paint about folks, what folks see and what folks do.”

In 1970, at the age of 69, Kitchens began to paint and draw, inspired by what he saw in the art studio of his son-in-law, in Boone, North Carolina. That son-in-law was William Dunlap, then a professor of art at Appalachian State University (and now one of Mississippi’s most recognized national artists).

The rapid evolution of Kitchens’ art, driven by his life experiences, his storytelling skills, his religious beliefs, and his inspired visions—all channeled through the crystal ball he consulted—brought him regional and national recognition in the 1970s.

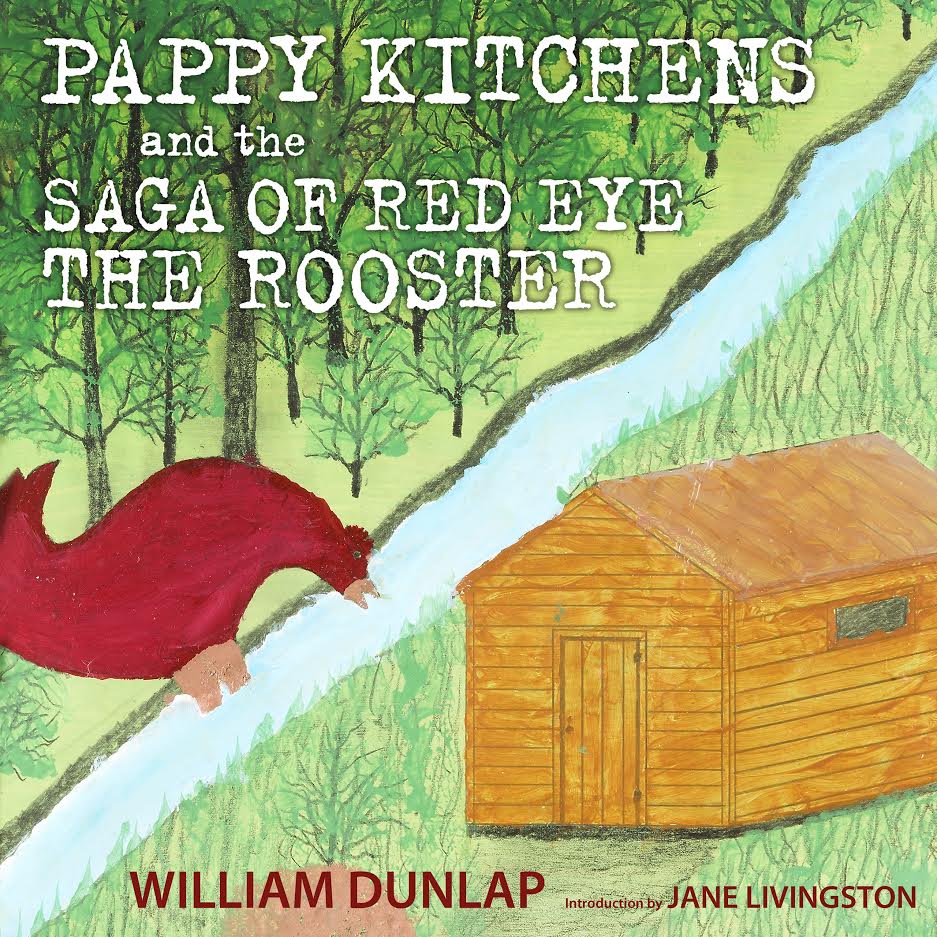

The art and life of Kitchens (1901-1986) is the subject of Bill Dunlap’s handsome, and thought-provoking, new book, Pappy Kitchens and the Saga of Red Eye The Rooster. Kitchens staged his ambitious project in a methodical fashion, as Dunlap notes in his Preface. “This fable consists of sixty panels, each one measuring fifteen inches square, composed of mixed materials on paper and executed in three groups of twenty from 1973 to 1977.” All sixty panels are featured in the book as individual full page, full color illustrations.

The story follows the life of this mythical bird “from foundling to funeral,” as Dunlap describes, tracing the arc of his allegorical adventures and his confrontations “with antagonists of all sorts, including his recurring nemesis, Colonel Harlan Sanders. Red Eye encounters violence, avarice, lust, greed, and, most of all, the seven deadly sins, dispatching them in heroic fashion until he finally succumbs to his own fatal flaw.”

In addition to Dunlap’s lively text, the book includes an excellent essay by noted curator and folk art scholar, Jane Livingston. Livingston included the “Saga of Red Eye” in the 1977 Corcoran Biennial Exhibition in Washington, DC, the first time folk art was included in this prestigious show. By 1977, the “Saga of Red Eye” had been “discovered” by the national art world.

More than forty years later, Livingston offers this observation. “Though it has taken nearly half a century for this book to enter the unpredictable trajectory of American cultural history, it comes at a moment when its authenticity and subtly intense truth-telling are especially welcome.” And she adds that “Pappy Kitchen’s work, once seen, is difficult to forget … in contemplating other artists … who were Pappy Kitchens’s chronological peers, his images resonate for me in a way that few of them achieve.”

This, alone, should give you enough reason to buy this book. Yet, there is another, equally intriguing side to this artist’s story. It relates to his self-awareness, and to current issues in the field of folk art (also known as “outsider,” “self-taught,” “naïve,” “vernacular” and more recently, “outlier” art). These issues question the proximity of self-taught art to contemporary art, increasingly arguing for its parity with more “elite” art forms.

Kitchens was a savvy character. He grew a beard and started calling himself Pappy. He read and studied art history. He referred to specific artists in his art and writings. This historical awareness is seen in his text (he hand wrote, then typed texts), “Preface—American Folk Art “ (included in the book), where he notes that the “first exhibition devoted to American folk art was held at the Whitney Studio Club, organized and sponsored by one Gertrude Whitney, in New York City in 1924.”

Today, a “folk artist” with this level of self-awareness might well be called “woke.” To underscore this self-awareness, he continued. “I sketch, draw, paint, talk, and write what I see, hear, read, feel, taste, and smell from a concept originating and composed from expierance [sic], my crystal ball, photographs, news medias [sic], archives and history, the Holy Bible, and a general knowledge of nature.”

It is time for Pappy Kitchens, and Red Eye, to be “discovered” yet again. He may have been a man ahead of his times.

J. Richard Gruber, Director Emeritus of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, is active as an independent art historian, curator and writer.

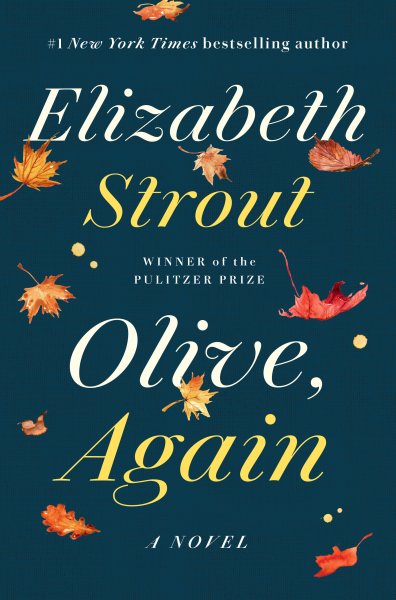

If you are already charmed—and simultaneously put off—by Olive Kitteridge of Crosby, Maine, welcome back. If you’re new to Elizabeth Strout’s expertly crafted small-town characters who face the same challenges as the rest of us, we’ve been waiting for you. Elizabeth Strout has released a sequel to her beloved book in this year’s

If you are already charmed—and simultaneously put off—by Olive Kitteridge of Crosby, Maine, welcome back. If you’re new to Elizabeth Strout’s expertly crafted small-town characters who face the same challenges as the rest of us, we’ve been waiting for you. Elizabeth Strout has released a sequel to her beloved book in this year’s  The resulting book from this author, photographer and artist is

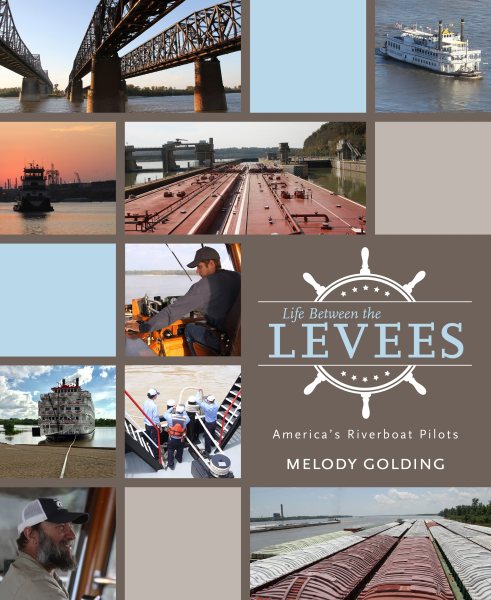

The resulting book from this author, photographer and artist is

Stories From 125 Years of Ole Miss Football

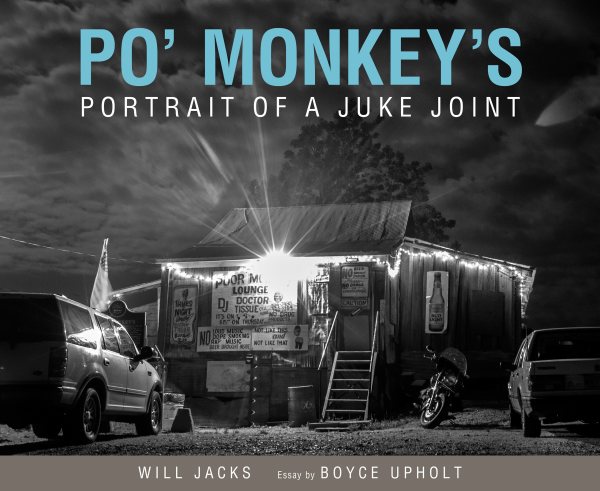

Stories From 125 Years of Ole Miss Football Mississippi Delta photographer and documentarian Will Jacks celebrates the life and times of the late Willie Seaberry, owner of Po’ Monkey’s blues house in Merigold for more than 50 years, in

Mississippi Delta photographer and documentarian Will Jacks celebrates the life and times of the late Willie Seaberry, owner of Po’ Monkey’s blues house in Merigold for more than 50 years, in

Over the years, Nevada Barr fans have grown to love the author’s sleuthing park ranger Anna Pigeon. However, in Barr’s new novel,

Over the years, Nevada Barr fans have grown to love the author’s sleuthing park ranger Anna Pigeon. However, in Barr’s new novel,  Reverberations remain from decades during which Southerners acted as if the Civil War was not concluded with the Confederacy losing. The narrative evolved through variations on a theme, but constant was diversion from discussion of a multiracial society.

Reverberations remain from decades during which Southerners acted as if the Civil War was not concluded with the Confederacy losing. The narrative evolved through variations on a theme, but constant was diversion from discussion of a multiracial society.