Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (September 23)

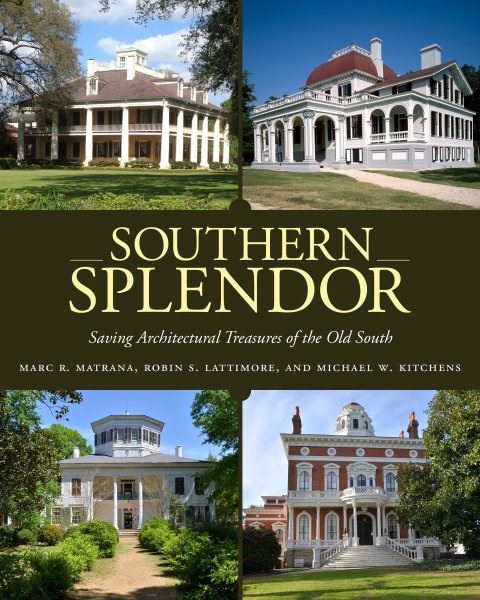

A shared interest in preserving a part of the South’s complex history, as expressed through its grand plantation homes of the antebellum years, has led three Southern historians to author their own definitive examination of many of these notable properties–with an eye toward explaining exactly why saving these “fragile relics of history” still matters today.

It took Marc R. Matrana, Robin S. Lattimore and Michael W. Kitchens–the authors of Southern Splendor: Saving Architectural Treasures of the Old South–nearly five years to merge and expand their collective research into this joint volume, published by University Press of Mississippi. The book explores nearly 50 restored or preserved homes built pre-Civil War.

It took Marc R. Matrana, Robin S. Lattimore and Michael W. Kitchens–the authors of Southern Splendor: Saving Architectural Treasures of the Old South–nearly five years to merge and expand their collective research into this joint volume, published by University Press of Mississippi. The book explores nearly 50 restored or preserved homes built pre-Civil War.

Matrana, a physician at Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans, is an active preservationist and historian and has authored Lost Plantation: The Rise and Fall of Seven Oaks and Lost Plantations of the South, both by UPM.

Lattimore, a resident of Rutherfordton, N.C., is a high school teacher who has written more than 25 books, including Southern Plantations: The South’s Grandest Homes. He was honored with North Carolina’s Order of the Longleaf Pine, one of the state’s most prestigious recognitions, in 2013.

An Athens, Ga., attorney and historic preservationist, Kitchens has authored Ghosts of Grandeur: Georgia’s Lost Antebellum Homes and Plantations. He was awarded the Benjamin Franklin Award for Best New Voice in Non-Fiction in 2013.

The book includes nearly 300-plus photos and dozens of firsthand narratives and interviews surrounding properties that have been restored as part of the historic preservation movement led by the South since the 19th century. Today, they say, only a small percentage of the South’s antebellum structures survive.

As co-authors of Southern Splendor, you all live in three different Southern states–how did you all get together to collaborate on this book–and have you worked together on previous books or other projects?

Robin S. Lattimore

Lattimore: We had all three written and published other books on antebellum houses in the past. We became friends first, because our paths often crossed when doing research, and then collaborators on this shared project because we respected each other’s work. Being from three different areas of the South actually served to provide greater depth of knowledge and experience to this project. The most gratifying part of making the decisions on which houses to feature in the book was being able to highlight some lesser-known properties alongside iconic treasures.

What is the goal of this book?

Lattimore: Our greatest hope for this book is to draw attention to the significant work done through the years by individuals, families, non-profit organizations, corporations, and others in restoring and preserving the South’s antebellum homes, many of which had once been in dire straits. The South’s antebellum architecture is being lost at an alarming rate due to neglect, fire, and increased residential, commercial, and industrial development. Ultimately, we hope that this book increases awareness of what we stand to lose if more historic homes are not preserved.

In Southern Splendor, you acknowledge that the South’s plantation homes represent a culture and lifestyle that was “made possible by an economic system that required the forced labor of enslaved people.” In what ways does your book examine that reality of Southern history?

Lattimore: As cultural historians, we are aware that plantation houses are at the epicenter of a complex web of human relationships that have shaped the social, economic, and political heritage of the South for generations. This project allowed us an opportunity to explore and celebrate the contributions made by African-Americans to the architectural heritage of the South, not just as laborers helping to construct grand plantation houses, but also the artistry and craftsmanship that people of color contributed to create these architectural masterpieces.

The book showcases antebellum residences in your home states of Louisiana, Georgia, and North Carolina, as well as half a dozen other states, including Mississippi. How were the homes from Mississippi chosen?

Marc R. Matrana

Matrana: We wanted this book to be a real celebration of preservation to showcase the fact that even the most destitute property can be saved from the brink of destruction if people care about it and decide to dedicate resources and efforts towards a project. We tried to find properties that had a strong preservation story behind them, like Beauvoir in Biloxi, which was almost destroyed by Hurricane Katrina. That historic home has since been meticulously restored to its former glory and the grounds, presidential library, and other facilities are better than ever. Or like Waverly (near West Point), a unique plantation home that was fully restored by the Snow family.

How did you become interested in this enormous task of preserving and restoring Southern antebellum homes?

Michael W. Kitchens

Kitchens: The path to becoming more than passively interested in preserving the South’s antebellum architectural treasures is somewhat different for everyone. However, I think I can speak for all three authors of this book by saying that our respective interests first arose when we visited some of these homes years ago. Visits turned into quests to read as much information about the homes as we could find. Reading turned into research; then research turned into a desire to share what we learned about the homes and histories with others by writing about them. All the while, each of us has become involved in activities and organizations whose purpose is to preserve the South’s historic structures. We hope that our efforts to record the histories of some of these homes may inspire others to take up the cause to preserve what we have left.

Could you briefly describe the main architectural styles of these homes? What inspired their designs?

Kitchens: The predominant architectural style in the South before 1861 was the Greek Revival style. Entire volumes are dedicated to explaining why this particular style was so loved in the South between 1820 and 1860. Many believe that Southerners saw themselves as being philosophically true to the Greek’s democratic ideas and chose the style to reflect that self-identification. However, an equally plausible explanation may be that the Greek Revival style was the prevailing style in Europe, particularly in England, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries when explorers were discovering Greek ruins across the Mediterranean. In the 1850s, the Italianate style became increasingly popular with Southerners as it allowed for asymmetrical designs which departed from the strict symmetry of Greek Revival designs.

Finally, Gothic Revival designs found their way into many corners of the South, harkening back to some of Europe’s great public and private architectural treasures from the Renaissance. The casual observer would be astonished to discover the wide variety of sizes and styles of antebellum architecture utilized in the South before 1860. It was far more diversified than just what we see in fictional film mansions such as Twelve Oaks or Tara.

A great deal of detail about these homes is included in “Southern Splendor”. How long did this project take, including the research?

Matrana: The book was a natural progression from the authors’ previous books, including my “Lost Plantations of the South”, Kitchens’ “Ghosts of Grandeur”, and many works by Robin Lattimore, including “Southern Plantations” published by Shire. We have each been separately researching Southern plantations for decades, each amassing large collections of materials, references, photos, etc. We started talking together about a collective project about five years ago and pitched the idea to Craig Gill at the University Press of Mississippi in the summer of 2014. We’ve been working on putting the book together ever since.

Tell me about the stunning photography in the book. How many photos are included?

Kitchens: The authors worked hard to select for this volume photographs which would not only illustrate the homes but evoke for the reader the raw beauty and majesty of these structures. There are over 270 color photographs and nearly 60 black and white photographs in Southern Splendor. It was our hope to illustrate how close some of these historic dwellings came to being lost forever. Many have already been lost to everything but memory. Some of the black and white photographs simply illustrate how a home looked decades ago. A few of these images date from the 1860s, and many of the black and white photographs were taken from the Historic American Buildings Survey which recorded the homes in photographs taken in the 1930s and 1940s.

But perhaps the most stunning photographs are color images showing the homes in their current state of restored splendor. Many of these photographs come from the authors’ private collections. Some photographs were donated for use in this book by the current owner of the house or museum. Still other images were provided by professional photographers retained by the authors to capture for the readers of this volume the most artful and stunning images possible. It is our hope that the readers enjoy these images and are inspired to visit and support the preservation of these and other historic structures.

The book states that many more of these historic homes are losing their battles with deterioration and decay than are possible to restore. In your estimation, what are the numbers, approximately–and why does saving these homes matter to us now?

Matrana: At the height of plantation culture, prior to the Civil War, there were almost 50,000 plantations in the South. Not all were associated with a grand mansion, but most were family estates. Today, only a few thousand plantation homes survive, and each year dozens are lost to fires, neglect, intentional demolition, etc. Hundreds of these homes are at risk today. Some sit in woods or fields rotting away, waiting for someone to rescue them from demolition by neglect.

Collectively, these structures represent our past–the good and the bad. The buildings were often constructed by slaves and provide real tangible evidence of slavery, a piece of our history which we surely must not forget. They provide a physical link to the past, which can never be restored once it is lost. As we’ve shown in Southern Splendor, restoring such homes can be an economic boom for local economies while simultaneously providing balanced education to the public about our shared history.

Marc R. Matrana and Robin S. Lattimore will be at Lemuria on Tuesday, October 2, at 5:00 to sign and discuss Southern Splendor.

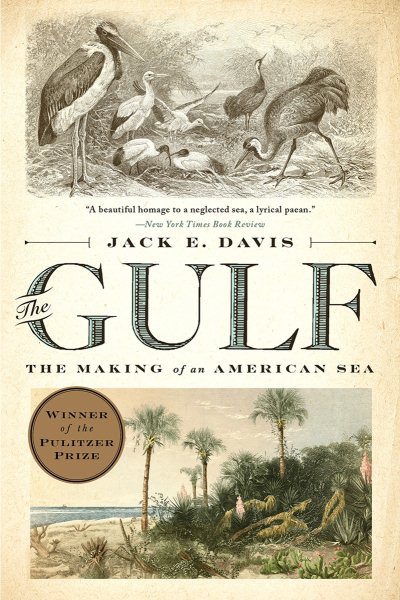

Davis said he wrote The Gulf because he was interested in restoring what he calls “an American sea,” to the conventional historical narrative of America.

Davis said he wrote The Gulf because he was interested in restoring what he calls “an American sea,” to the conventional historical narrative of America.

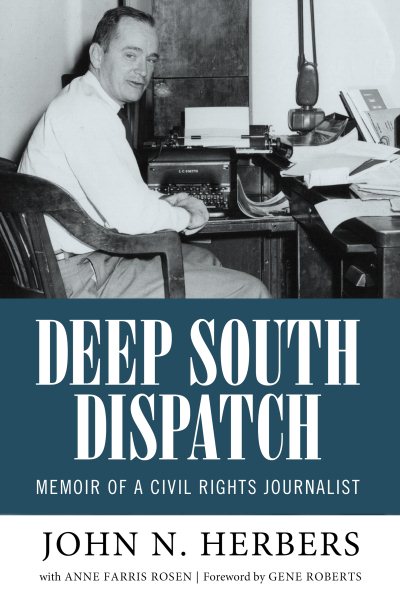

Subtitled “Memoir of a Civil Rights Journalist,” Dispatch is a fascinating behind-the-scenes account of the arc of his reporting, from covering the Emmett Till trial, to the Birmingham church bombing, to marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Kennedy assassination. But it’s not merely a rehashing of old events.

Subtitled “Memoir of a Civil Rights Journalist,” Dispatch is a fascinating behind-the-scenes account of the arc of his reporting, from covering the Emmett Till trial, to the Birmingham church bombing, to marching with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the Kennedy assassination. But it’s not merely a rehashing of old events. But it goes far beyond a simple retracing of his steps here and his return to Washington that resulted in massive changes in federal food programs for the poor.

But it goes far beyond a simple retracing of his steps here and his return to Washington that resulted in massive changes in federal food programs for the poor. Hal & Mal’s is not one story, but many, and the book sheds a warm and witty light on the background and influences that fed into this cultural outpost in Jackson’s downtown. Of all those vines, family clings the strongest with tendrils in every story of the boys who grew up in Perkinston and Booneville, lost their mother young, and held the love of father, stepmother, brother, grandparents, relatives and friends close.

Hal & Mal’s is not one story, but many, and the book sheds a warm and witty light on the background and influences that fed into this cultural outpost in Jackson’s downtown. Of all those vines, family clings the strongest with tendrils in every story of the boys who grew up in Perkinston and Booneville, lost their mother young, and held the love of father, stepmother, brother, grandparents, relatives and friends close. Their new book,

Their new book,

Perhaps others among you received a more comprehensive education at your own schooling or by your own volition, but for anybody who considers themselves a true Jacksonian, I cannot recommend highly enough Josh Foreman and Ryan Starrett’s

Perhaps others among you received a more comprehensive education at your own schooling or by your own volition, but for anybody who considers themselves a true Jacksonian, I cannot recommend highly enough Josh Foreman and Ryan Starrett’s

The University Press of Mississippi, working with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, have published

The University Press of Mississippi, working with the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, have published