Interview by Jana Hoops. Special to the Clarion-Ledger Sunday print edition (April 28)

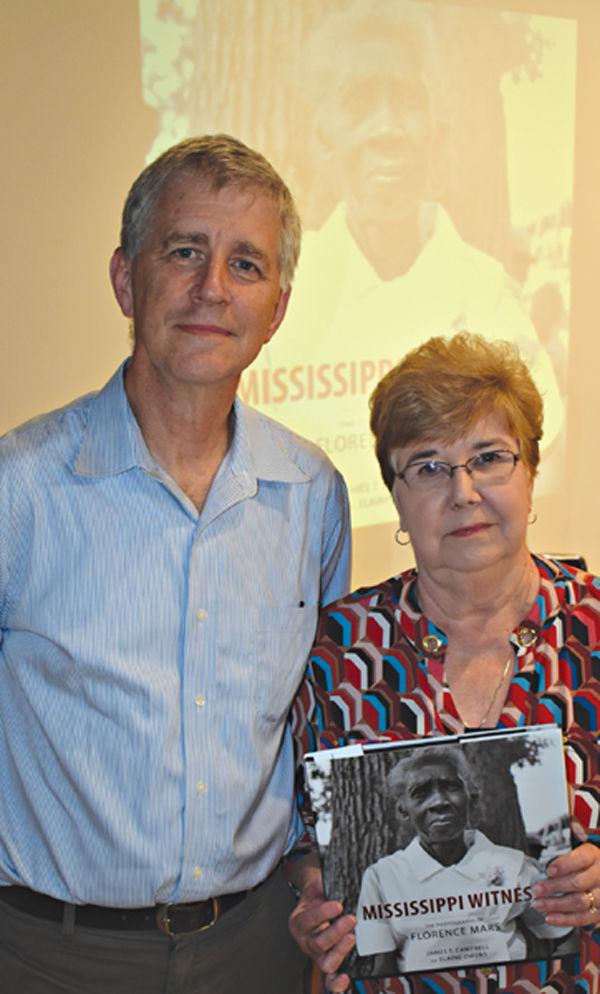

It was the teamwork of Stanford professor James T. Campbell and Elaine Owens, the former head curator of photographs at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, that resulted in the publication of a significant photography collection that was almost swept aside by history.

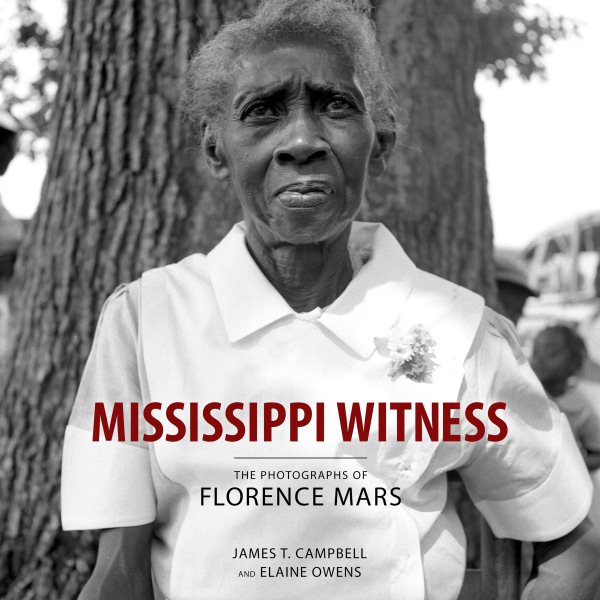

Mississippi Witness: The Photographs of Florence Mars (University Press of Mississippi) showcases images taken in and around Neshoba County in the 1950s and ’60s by civil rights activist Florence Mars of Philadelphia, Miss., during a turbulent time in the state’s history. The volume is filled with stunning black and white photos and a comprehensive and informative introduction by Campbell.

Mississippi Witness: The Photographs of Florence Mars (University Press of Mississippi) showcases images taken in and around Neshoba County in the 1950s and ’60s by civil rights activist Florence Mars of Philadelphia, Miss., during a turbulent time in the state’s history. The volume is filled with stunning black and white photos and a comprehensive and informative introduction by Campbell.

Former governor William Winter, a friend of Mars, has said her pictures “spoke volumes,” and calls this book “an important volume in this period of our nation’s history.”

How did the idea of producing this book come about, and how did the two of you get together?

James Campbell and Elaine Owens, courtesy of the Greenwood Commonwealth

Campbell: I first learned about the photographs from Florence Mars herself. I was doing research related to the 1964 Mississippi Summer Project and naturally found my way to Neshoba County and, soon enough, to Miss Mars. I had an opportunity to interview her several times before her passing in 2006, and in one of those conversations she told me about her photos, which she had deposited at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History in Jackson.

Owens: Prior to my retirement, I worked as head curator of photographs at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. That’s where I met Dr. Campbell. We agreed that Mars’s photographs should be shared with the public and a book was the best way to do that.

Tell me about Florence Mars, and the historical significance of the story behind her photographs.

Owens: The majority of the photographs were taken between 1954 and 1964. According to Mars herself, they were prompted by the landmark Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education (in 1954), which signaled the end of legal segregation in the South. Her intent was to document a Jim Crow world that she knew was disappearing. She had no idea that she and her community would later be caught up in one of the most notorious events of the whole Civil Rights era.

Campbell: One thing I found interesting was that Mars made virtually no effort to publish or exhibit her photos. To the best of our knowledge, she never sold one for money. But she spent hours traveling around the countryside taking photographs, and hours more printing the images in the homemade darkroom she built in an upstairs hall of her house. They were her private devotion, her way of making sense of the world around her.

Explain why your book is titled Mississippi Witness.

Owens: Mississippi Witness is meant to echo the title of Ms. Mars’s own book, Witness in Philadelphia, which was published by LSU Press in 1977.

Campbell: The title of Mars’s book is kind of a pun. On one hand, the book is her first-person account of the events of 1964, of the murders and their aftermath in her hometown. But she was also a witness in another sense, when she agreed to testify in a federal trial that exposed local law enforcement’s brutal treatment of black citizens. She paid a real price for that decision.

Owens: Our book, Mississippi Witness, shows Ms. Mars acting as a witness in yet another sense, as a photographer.

The pictures literally “speak for themselves,” as they are presented, just one per page, on 101 of the 134 pages in the book, with no text at all. The “List of Photographs” in the back reveals that many of the subjects are unidentified; and some photos have no date listed–not even the year. Why did you decide to present the photos in this dramatic way?

Owens: We were simply trying to honor the photographer’s intent, to let the images, as you say, speak for themselves.

Campbell: We included such identifying information as we had in an appendix at the back of the book, but we decided not to have any accompanying text with the pictures themselves, nothing to pull your eye away from the image. I think it was the right decision.

As for not knowing who some of the people in the images are or when particular photos were taken: I suppose that’s true, but by the standards of a lot of documentary photography collections–the Depression-era images of the Farm Security Administration photographers, for example–what’s striking about Mars’s photos is how much we do know. She noted where many of the photos were taken and she recorded the names of at least some of the people in them. She knew a lot of these people personally–Neshoba County is not a very big place–and she routinely shared prints of the images with her subjects, which is something too few photographers think to do.

Jim, please tell me what your primary role was in the production of this book, and why this project was important to you. The history you present in the introduction is very through!

Campbell: Thank you. Mars herself used to say that in order to understand someone you needed to “know the background.” So hopefully the introduction helps people to understand a bit about who she was and how the photographs came to be. But the real value of the book is to be found in the photos themselves. They are just haunting–beautiful and heart-rending all at the same time. They capture truths about our history–not just the history of Mississippi, but American history as a whole–that we need to face squarely.

Elaine, please tell me what your primary role was in the production of this book, and why this project was important to you. You must have searched out a great many details in collecting and curating these photos!

Owens: As curator of photographs at MDAH, I’ve looked at a lot of photographs of Mississippi, but few if any collections have the depth and scope of the images in the Mars collection. We spent many hours debating which images to include in the book. We wanted images that evoked particularities of time and place, but we also wanted to show Mars’s strengths as a documentary photographer, not only her unfailing eye but also her technical skill. I just felt that these images needed to be shared. I also wanted to honor the courage of one woman who stood up to powerful forces of evil at great personal risk.

Signed copies of Mississippi Witness are still available at Lemuria’s online store.

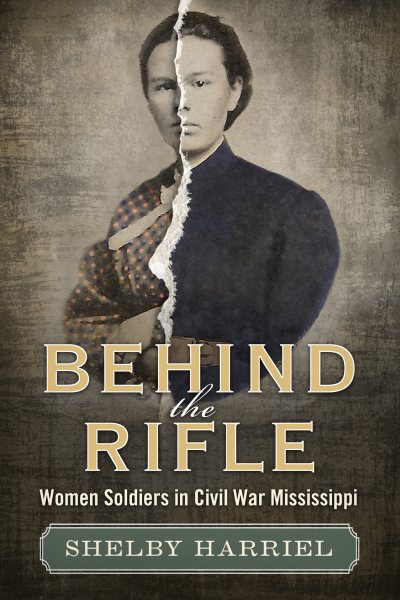

That curiosity eventually led to published research in newspapers, magazine, website, and blogs about the role of women in the Civil War.

That curiosity eventually led to published research in newspapers, magazine, website, and blogs about the role of women in the Civil War.

In his first book,

In his first book,

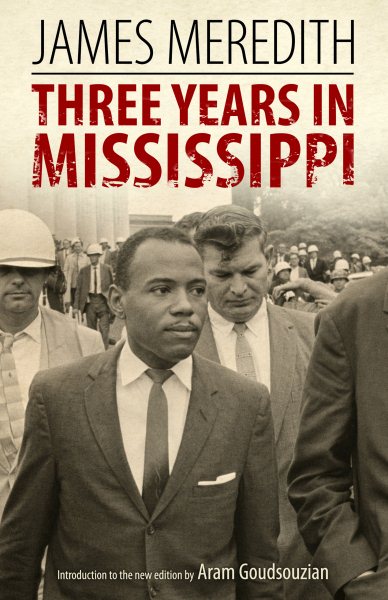

Famous for integrating the University of Mississippi in 1962, Meredith has been a challenging and criticizing voice in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi ever since. In some ways, Meredith started it all in his home state, and he documented that struggle in his first book

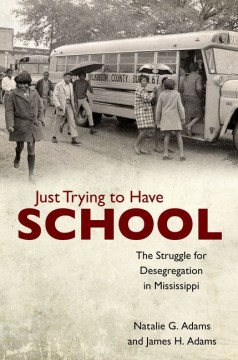

Famous for integrating the University of Mississippi in 1962, Meredith has been a challenging and criticizing voice in the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi ever since. In some ways, Meredith started it all in his home state, and he documented that struggle in his first book  Both James and his coauthor Natalie G. Adams could identify with this sentiment firsthand. They, too, had experienced desegregation 45 years before Johnson closed a phone call with those fitting words. James and Natalie kept digging, and the result is the sweeping history

Both James and his coauthor Natalie G. Adams could identify with this sentiment firsthand. They, too, had experienced desegregation 45 years before Johnson closed a phone call with those fitting words. James and Natalie kept digging, and the result is the sweeping history

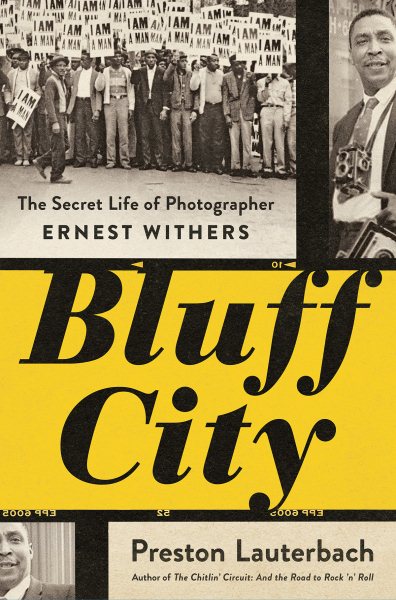

Former Memphis resident and popular historian Preston Lauterbach puts a new focus on that city’s Civil Rights-era story–including that of critical events that led to the death of Martin Luther King, Jr.–in his newest book,

Former Memphis resident and popular historian Preston Lauterbach puts a new focus on that city’s Civil Rights-era story–including that of critical events that led to the death of Martin Luther King, Jr.–in his newest book,

Robertson is a former Mississippi Supreme Court justice, a long-time practicing attorney, and a frequent law professor. He recounts ten occasions from statehood to the late 1940s when the Mississippi constitution impeded or impelled justice. Fortunately for our enjoyment, John Grisham’s comment on the book’s cover that Robertson is a gifted storyteller is spot on.

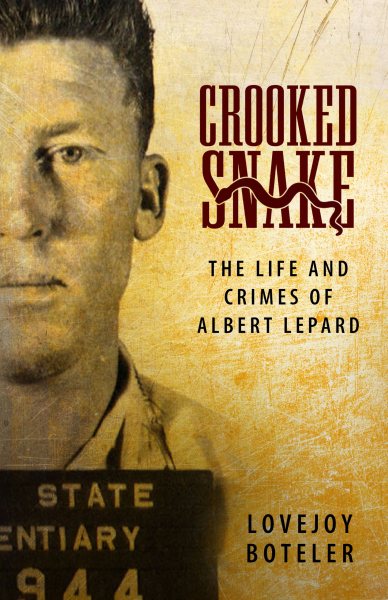

Robertson is a former Mississippi Supreme Court justice, a long-time practicing attorney, and a frequent law professor. He recounts ten occasions from statehood to the late 1940s when the Mississippi constitution impeded or impelled justice. Fortunately for our enjoyment, John Grisham’s comment on the book’s cover that Robertson is a gifted storyteller is spot on. From 1920 until 1933, Prohibition was the federal law of the land, banning alcohol across the country. But in Memphis, Prohibition lasted under state laws from 1909 until 1939. On page after page, author Patrick O’Daniel shows that Prohibition “led to increased crime, corruption, health problems and disrespect for all laws for three decades.”

From 1920 until 1933, Prohibition was the federal law of the land, banning alcohol across the country. But in Memphis, Prohibition lasted under state laws from 1909 until 1939. On page after page, author Patrick O’Daniel shows that Prohibition “led to increased crime, corruption, health problems and disrespect for all laws for three decades.”