The Great Migration by Jacob Lawrence. New York: Harper Collins / The Museum of Modern Art & The Phillips Collection, 1993.

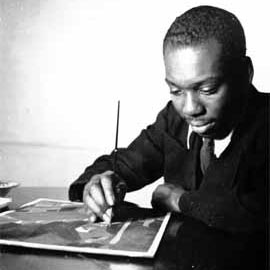

Jacob Lawrence was not your typical painter. He often spent months at a branch of the New York Public Library, taking notes from journals and books and other documents before he would began work on a formal painting project. Lawrence wanted his art to teach history to his people. In describing his research efforts for The Great Migration, Lawrence remarked:

Jacob Lawrence was not your typical painter. He often spent months at a branch of the New York Public Library, taking notes from journals and books and other documents before he would began work on a formal painting project. Lawrence wanted his art to teach history to his people. In describing his research efforts for The Great Migration, Lawrence remarked:

“Having no Negro history makes the Negro people feel inferior to the rest of the world . . . I didn’t do it just as a historical thing, but because these things tie up with the Negro today.”

Jacob Lawrence’s family was a family of migration. His mother and father had left the South for New Jersey where Jacob was born in 1917. Jacob ended up in Harlem at the age of 13. His mother and art teachers saw his talent at a young age, and eventually his talent earned him a position in the WPA program which provided the first artistic opportunities for many black artists like him. After Lawrence’s position at the WPA ended, he applied for a grant from the Julius Rosenwald Fund (of Sears & Roebuck) and cited his unusual research needs as a painter in the application. He asked for six months of research time before he began painting the Great Migration series.

The Great Migration consisted of 60 small tempera paintings depicting the mass migration of African Americans from the South to the North after World War I. The paintings were accompanied by captions which showed the influence of modern media: the rise of graphic illustration in mechanically produced magazines and photo books. The photo book with accompanying text was a popular genre following the Great Depression.

Many New Deal programs were designed to document rural America through oral-history projects and photography series.

Many New Deal programs were designed to document rural America through oral-history projects and photography series.

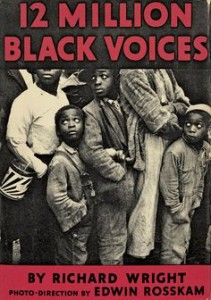

Well-known photo books from this era include: Erskine Caldwell’s and Margaret Bourke-White’s “You Have Seen Their Faces” (1937); Dorothea Lange’s and Paul Taylor’s “American Exodus” (1939); “12 Million Black Voices” by Richard Wright (1941); and James Agee’s and Walker Evans’s “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men” (1941).

Lawrence chose this same format—he only altered the format with his striking paintings. In 1941, the enlarged photographs from “12 Million Black Voices” with text by Richard Wright were chosen to accompany Lawrence’s Great Migration panels on a 15-city tour.

In 1993, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Phillips Art Collection released a signed limited edition book of 100 copies of The Great Migration with all 60 panels and captions.

In 1993, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Phillips Art Collection released a signed limited edition book of 100 copies of The Great Migration with all 60 panels and captions.

In 2015, MoMA and Phillips released a new book, “Jacob Lawrence: The Migration Series,” following a 2014 exhibition celebrating the artist’s life and work.

Written by Lisa Newman, A version of this column was published in The Clarion-Ledger’s Sunday Mississippi Books page.

Comments are closed.